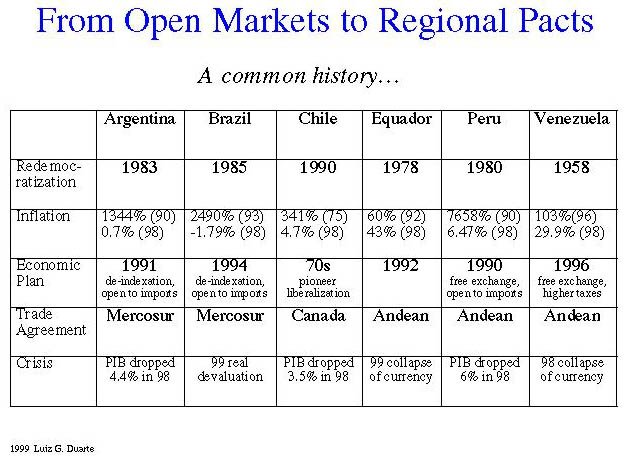

In the 1990s, most countries south of the Rio Grande"with the notable exception of Cuba"initiated a liberalization process marked by intense privatization, fall of protectionist barriers and alliance to neighboring countries in regional trade pacts. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, the Mercado Comun del Sur (Mercosur) in 1991, the Andean Pact in 1988 and even the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA) of 1994 were examples of such pacts. In 1994, Brazil proposed setting up a web of free trade agreements with neighboring South American countries. Negotiations have been carried out, jointly, by all Mercosur members to establish FTAs with the other South American countries or sub-regional groups of countries in ten years. In 1996, free trade agreements with Chile and with Bolivia were signed and in the following year, other agreements between Mercosur and Andean Pact members got under way (1999). Not by mere coincidence, Latin America started to grow again in this decade, after several years of stagnation. Commerce among partners intensified and the sudden prospects for growth called attention of American multinationals, eager to secure their existing foothold in a region traditionally used as an extension market to gain the economies of scale necessary to compete with the European and Japanese competitors. Already in 1994, Latin America was the fastest growing U.S. export market, taking almost $90 billion worth of U.S. goods. By the end of the decade, the American Commerce Dept. estimated the region would surpass Europe as a customer for U.S. wares and the recent crisis has not significantly changed expectations that, by 2010, it will surpass Europe and Japan combined (Harbrecht, Smith and DeGeorge, 1994).

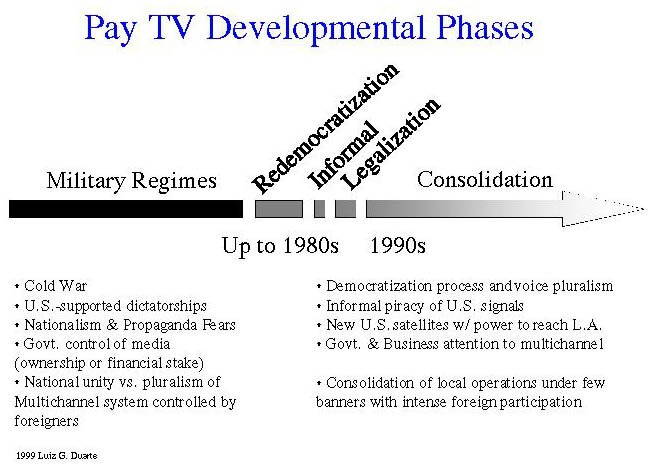

Accompanying this liberalization process, the pay television industry flourished as old restrictive laws started to fall or be simply ignored, allowing foreign investment to flow in. In Venezuela, for example, U.S.-sponsored advertising in pay-TV grows exponentially, despite lingering prohibiting laws. American cable industry consultant Paul Kagan estimates that approximately $375 million had already been poured into Latin American cable and satellite companies in the first three years of this decade (DeGeorge, 1993) and the number has dramatically increased since then. From Multiple System Operators (MSOs) like TCI to satellite providers such as DirecTV, not to mention investment firms such as American Express and Chase Manhattan, dozens of American companies entered the race to associate themselves with the largest local players. They rushed to the relatively unexploited Latin American pay-TV market, however, just to find themselves tangled in a jungle of yet-to-be-defined laws, bureaucracies and other idiosyncrasies of the Hispanic and Brazilian cultures.

Thanks to the current economic crisis in Brazil, which spread around the region, many companies have already withdrawn, while others have significantly reduced their investments. But a handful of powerful players remained, convinced that their continued presence "in one way or another" in a few key countries will secure their share of a future unified and prosperous Latin American market. The case of the Venezuelan MSO SuperCable, partially owned by American MSO Adelphia Cable Communications is a good example. Foreign involvement in the enterprise goes well beyond the 20% limit imposed by the government, as another 20% share is owned by Ecuador's Eljuri Group, whose American backing is not at issue. Eljuri, however, is considered a domestic shareholder, due to the country's participation in the Andean Pact trade bloc with Venezuela (Dahlson, 1999). This paper reviews the legal environment in which this and other pay-TV companies in the region are striving to secure the American financial backing while lobbying to pass foreign-friendly national regulations, as well as region-wide rules that will impact all members of the trade pacts.

From protectionism to open markets Foreign television companies and general investors in Latin American media have been forced to cope with Latin American governments' various approach, timing, and vision for the telecommunications sector's structure. Overall, however, researchers have recognized that the general trend for development of the sector has been advancement in stages. In the case of telephony services, the stages seem to go from state-owned monopoly to private "transitional monopoly," and finally, to competition (Harbrecht et al., 1994). And, while less studied, advancement of the subscription television services can be divided in stages as well. From the informal period when the "Pirates of the Caribbean" were just an annoying social phenomenon (Hoover and Britto, 1990), to the first government attempts to regulate the industry in the early 1990s to the current stage of business consolidation, the sector in various Latin American countries has reached different stages of development.

As it happened in the United States, the early stage was characterized by small local enterprises. In Brazil, for example, one of the pioneer cable plants was run by father Jos Antonio de Lima in the small countryside town of Santo Anastcio (Sao Paulo), where 250 subscribers started receiving retransmissions of distant over-the-air channels (Duarte, 1996). In the Caribbean, local entrepreneurs took advantage of their proximity to the U.S. territory to "informally" redistribute American TV signals then freely available from the U.S. satellites (Ebanks, 1989). The proliferation of pay-TV plants and the new democratic tones of Latin American governments then led to the recognition of new channels of communication and the second stage of development. Most countries living this stage regulated the sector, sometimes barring and sometimes fostering foreign participation. The entry of foreign strategic investors into a Latin American country that is opening its telecommunications market has traditionally occurred in a pan-regional mode and as a strategic alliance strategy.

Considering the untested waters of Latin American pay-TV markets, new competitors in this regulated market are often consortia of in-country local partners who interrelate in and know the local business environment, and foreign strategic investors, including telecommunications companies with technical and managerial expertise and financial partners. The formation of joint ventures and associations between Latin companies and their foreign partners may be lengthy and complex, particularly when there are multiple parties on both sides of the venture (many times a financial requirement in the case of expensive multichannel ventures). Companies sometimes undergo negotiations with more than one partner before finding the right fit. Before the commencement of competitive services, two or more strategic alliances that would otherwise compete in the opening market may combine to create a larger and more powerful presence in the marketplace.

Illustratively, American satellite company Hughes Electronics sought an association with Brazilian Globo TV before associating itself to Abril TV and finally appropriating all Brazilian operations. The most powerful media conglomerates from Brazil and Mexico decided, on the other hand, to cooperate in a pan-regional satellite distribution system. Sky Network is a holding formed by Brazilian Globo TV, Mexican Televisa, and the two American giants News Corp and TCI. In Venezuela, SuperCable and InterCable gobbled up most of the local firms to control most of the country (Dahlson, 1999).

Strategic alliances, nevertheless, do not reduce the complexity of the process of getting involved in a variety of local markets. There are several legal and administrative steps to consider. As the joint venture company that will operate in the local market is formed, its partners make capital contributions to fund the start-up of operations. In connection with marketing telecommunications services, for example, the parties also must determine whether, and under what circumstances the venture will be entitled to use trademarks, trade names, service marks and logos of the partners. Barbour (1997) emphasizes that the parties should then sign appropriate license agreements. The local partner may negotiate for the licenses to be exclusive in the country where the joint venture operates with respect to telecommunications services provided by the joint venture.

The joint venture company must obtain appropriate import licenses or authorization from the country. The venture must apply to the telecommunication authority for licenses and permits that it needs to render the services contemplated by its business plan. Even if the venture is formed substantially in advance of the opening of competition in basic services, the venture may apply for permits and licenses related to value-added and other services that are already competitive. Also, contracts with third parties, such as floor space leases, equipment leases, supply purchase agreements and employment agreements with key executives of the new venture company will be executed. If the joint venture plans to construct new network facilities, then the venture must also select a contractor and enter into contracts for design, engineering and construction. With the placement of personnel and the commencement of operations, this is also a critical time in a venture for cross-cultural communication and adaptation, in terms of differing national cultures as well as corporate cultures.

Such corporate organization takes place in the midst of several regional and sub-regional trade agreements that have greatly transformed the legal and bureaucratic environments in which firms do business. Most times, these agreements have put down barriers to commerce and facilitated cross-border transactions. In the specific case of a venture between United States and Mexican partners, NAFTA may afford substantial advantages to the joint venture's procurement of materials and equipment. Effective January 1, 1993, NAFTA eliminated duties on "category A" items, which included substantial categories of United States-manufactured telecommunications infrastructure and consumer equipment. However, in a few cases, they have also made the market structures even more complex for the already perplexed foreign investor.

This is the case, for instance, of trademark regulations within the Andean region. Andean Pact Decision 344 sets out minimum standards for trademark registration and protection in the member states. One would thus expect the member states would have relatively simple and uniform laws for registering and protecting trademarks. This, however, is not the case. Each member country applies its own procedural regulations for implementing Decision 344.

These procedural aspects, in addition to other factors, creates significant variations in trademark practice from country to country (Hasselt and Fernandini, 1996). Until recently, it has been unclear whether Decision 344, or any part of the Andean Pact, is enforceable in Bolivia. Bolivia has assented to Decision No. 7 of the Cartagena Agreement Round (Andean Pact), which establishes that the terms of the Andean Pact are automatically enforceable in all adhering countries, without the need for ratification by the countries' legislatures. As a result, Bolivia continued to apply its Trademark Law of 1918, and the decisions of the Andean Pact were not carried out in the country.

Although no single application can register a mark in all five member countries, a first-filed application in one member state can be sufficient to exclude anyone else from using the mark in other member countries. It is thus never sufficient to conduct a trademark search merely in the country in which one wants to register the mark. Searches should be conducted in all five member countries. The Paris Convention itself is in force in Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador, so these countries grant a six-month priority to trademark applications filed in other Paris Convention countries. In Venezuela, the Paris Convention has been approved by Congress, but is not yet enforceable. In Peru, the Paris Convention has been in force only since April 11, 1995, so Paris Convention priorities can be claimed only for applications filed no earlier than that date.

Due to delays in publications and other political and economic factors, the time required to obtain registration of a trademark (if no oppositions are filed) varies from country to country. It may take as little as four months (in Peru), or as much as a few years (in Venezuela), depending on the current situation.

The Andean group, as well as some of its individual members, is currently negotiating with the Mercosur Group (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay). The goal is to integrate both blocs into a common market that would encompass most of South America. It is already challenging to design and implement a strategy for dealing with the economic, political and procedural variations of trademark registration in the Andean Pact countries, and these countries share common trademark legislation. One can expect a much greater challenge when one must also take into account the Mercosur states, which have different trademark legislation.

Foreign Investment in Latin America

In each step of the foreign involvement in Latin America's telecommunication industry, specific legal and contractual issues impact upon the business plan and the financial viability of the investment. These key issues generally apply to all participants who enter a given country at any particular stage of development of the sector. Transactional counsel to a strategic investor in telecommunications in Latin America coordinates closely with business executives and in-house counsel about these issues and their impact on the valuation of the investment opportunity and the business plan. In order to better understand the legal environments in which these new pay-TV enterprises struggle to operate, appropriately harmonizing the interests of foreign investors and local managers, a review of each country's rules was compiled from several reports by attorney offices around the region.1 In all countries, as it will be demonstrated, regional trade pacts have started to impact the legal parameters of television operations, thus inevitably demanding adaptations in the strategies adopted by foreign allies in the pay-TV business.

Argentina Foreign investments in Argentina are governed by Argentine Foreign Investment Law No. 21,382 of 1976, amended in 1980 and 1989, including the Regulatory Decree No. 1225/89 (FIL). Short of granting special incentives to foreign investors in order to promote their settlement in the country, FIL provides, as a general principle, that foreign investors shall have the same rights that the constitution grants to local investors. For the FIL, foreign investors are "any individual or corporation domiciled abroad and the so-called "foreign capital local firms," that is, any firm domiciled in Argentina in which individuals or corporations domiciled abroad should own directly or indirectly no less than 49% of the capital or possess directly or indirectly the number of votes needed to have a majority vote in shareholders meetings" (Marval and Pellegrini, 1993).

Since the Economic Emergency Law No. 23,697 was enacted in 1989, liberalizing and simplifying the legal frame in force until then, no prior approval is required to make foreign investments in Argentina. In addition, the ability of foreign investors to participate in privatizations may be limited by the specific regulations issued by the government in each case. Unless specific prior approval is required, foreign investors may elect not to register their investments under FIL, in which case they will be subject to the same exchange controls as local residents. Presently, there are no restrictions on exchange transactions.

In the past, during periods when exchange controls have been in force, only registered investors have had the right to purchase foreign currency (or Argentine External bonds denominated BONEX) at the official rate of exchange to remit dividends and repatriate capital. Even during periods of exchange controls, however, all foreign investors have been able to repatriate investments from Argentina by purchasing BONEX in the secondary market with local currency and selling them outside Argentina for U.S. dollars since there are no restrictions on the movement of BONEX out of Argentina. BONEX are U.S. dollar denominated government bonds which yield interest semiannually at LIBOR and have an active secondary market, both in pesos and in U.S. dollars in Argentina and in U.S. dollars in Montevideo and New York. There are no limits for profit remittances, whether foreign investors are registered or not, nor is there obligation of association with residents.

Since 1989, the foreign exchange market was liberalized after more than four decades of strict control. At present, foreign currencies may be freely purchased, sold or transferred from or towards the country, as the law allows foreign currency deposits at domestic banks with the guarantee of no confiscation or forcible conversion into local currency of such deposits by the government. In order to control inflation and to stabilize the economy, the current government has encouraged a monetary reform without precedents. In March 1991, the convertibility of the austral, Law No. 23,928, was enacted and on November 1, 1991, the National Executive Power issued Decree No. 2284/91 (the "Deregulation Decree"), which significantly reduced certain regulations relating to a number of economic activities which had previously limited the contractual freedom of economic agents or which had resulted in procedural difficulties generating high transaction costs.

The most significant changes introduced by the Deregulation Decree were:

- the abrogation of import restrictions and quotas;

- the abrogation of several taxes and duties imposed on the internal and external commercialization of certain products, including the abrogation of the 3% statistical tax on exports;

- the abrogation of stamp duty with respect to acts and transactions relating to the issue of securities by companies authorized by the Comisin Nacional de Valores (National Securities Commission) to publicly offer such securities;

- the abrogation of the tax on the transfer of securities and the tax on the sale of foreign exchange; and

- the exemption from the payment of income tax on capital gains earned by foreign beneficiaries arising out from securities transactions.

In 1989, the State Reform Law proposed by the government was passed declaring 32 state enterprises eligible for privatization (the number of eligible enterprises was increased in 1990). In addition, to increase the efficiency of public sector enterprises, the privatizations are intended to provide cash to reduce the public sector deficit and to reduce the government's external debt through selective use of debt-equity conversions. In the case of ENTel, in November 1990, the government sold a 60% stake in each of two operating companies created from the existing telephone company for a total of US$214 million in cash and US$5 billion payable in Argentine external sovereign debt. The Argentine government has since sold its remaining interest in Telecom Argentina and in Telefnica de Argentina S.A. (the two operating companies set up after the initial incorporation of ENTel in November 1990) through a public offering in Argentina and abroad for a gross price of US$2.1 billion.

Overall, Argentina is one of the most aggressive in opening its markets to the world. Several laws have recently approved the Investments Promotions and Reciprocal Protection Treaties signed with the United States, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Poland, France, Spain, Canada and Sweden. While inflation remains low and the influx of imported capital goods has been immense, the majority of the population has difficulties in acquiring such new items as they suffer with high unemployment rates consequence of the demise of poorly equipped local manufacturers, incapable of competing with international players.

Television Law

Radio communication services between land stations and space stations, or between space stations, or between land stations when signals are retransmitted by space stations, are also regulated by the Telecommunications Law No. 19, 798 (Agatiello, 1994). CNT is in charge of administering the radioelectric spectrum, of issuing measures to provide satellite services and of authorizing the use and installation of satellite systems for telecommunications. Any matter related to transmissions by satellite broadcasting will be regulated by both the Comfer and CNT. The transportation of signals for distribution purposes to cable television channels or for private use has been liberalized. Therefore, only an authorization is needed for the use of the frequency if the signals are to be transported through the radioelectric spectrum. Since June 1993, authorizations to install and operate systems, equipment or instruments exclusively destined to the reception of radio and television signals issued through communication satellites are no longer required.

Direct broadcasting to the general public is regulated both by the Radio Broadcasting and the Telecommunications Laws. Regarding open-air television, Decree No. 1151 of 1984 suspended all public bids for air TV and radio services provided through the radioelectric spectrum. Since 1984, however, approximately 1150 licenses for cable television broadcasting have been granted by Comfer.

Argentine law has no restrictions on foreign investments in telecommunications. Indeed, the majority interest in the two companies that provide basic telephone service and in the three that provide the mobile cellular service is held by foreign companies. However, Argentina still restricts the ability of foreigners to be licensors of radio broadcasting services. Article 45 of the Radio Broadcasting Law states that the licenses must be granted to Argentine individuals and/or legal entities domiciled in Argentina. The licensees must not be affiliated, controlled or directed by foreign individuals or foreign entities. The individual shareholders must be Argentine natives or naturalized, in both cases residing in Argentina for at least 10 years. Article 45 of the Radio Broadcasting Law has been severely criticized over the years. This limitation will probably be abrogated in the near future as a bill providing for its lifting is currently before the National Congress.

Bolivia Back on September 17, 1990, the Bolivian government passed its Investment Law which grants several guarantees to the foreign investor (Rojas and Rojas, 1993). There is no foreign exchange control and banks are operating with current accounts or deposits in dollars or in bolivianos. To encourage foreign investment, Bolivia has signed bilateral treaties with several countries, such as Italy, Spain, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Great Britain and China. The government has also ratified the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agreement (MIGA) proposed by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. A respective agreement is being negotiated with the United States. Several state-owned companies are being privatized. With the countries of Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela, as well as Peru, free trade agreements have been executed. Also, with Peru, an agreement called Mcal has been executed.

Brazil The investment of foreign capital in the country is regulated by Law No. 4.131/62 (modified in 1964 and 1991), regulated by Decree 55.762/65 and complemented with regulatory acts issued by the Central Bank of Brazil. The control of inward and outward investments is carried out through the registration of such investments with the Central Bank of Brazil. Once having submitted and having obtained from the Central Bank of Brazil the registration of the investment, the Central Bank will issue a certificate which allows the foreign investor to receive dividends in his country, as well as to return the capital invested. In general, any payment made by a Brazilian source to a person domiciled abroad is subject to a 25% withholding tax. (2) Such rate can be reduced in the event the recipient of the payment is domiciled in a country with which Brazil has entered into a tax treaty to avoid double taxation.

Since March 15, 1990 when President Collor took office and announced the new economic policy, there has been great expectation about radical changes in the legislation relating to foreign investments (Castro, Barros, Sobral, and Xavier, 1993). Despite some numerous retreats' including the impeachment of Collor'some advances have been obtained to open the national market to foreign involvement, thus obliging the national sector to get used to a free market policy where no protectionist measures and no subsidies will soften the competition. Although the old law on foreign capital (Law No. 4.131) has only suffered minor changes, they were significant enough to lower the tax burden on foreign investment and spark a change in the bureaucracy's state of mind. The latter greatly helped reduce the difficulties previously experienced by investors in remitting dividends abroad or registering reinvestments, which were attributed mostly to the way the public bodies, such as the Central Bank, would interpret and enforce the rules. Since the Central Bank used to hold the power to legislate on the matter, a rather unstable situation distressed the holders of foreign investments in Brazil.

A sign of advance in welcoming foreign trade was the creation of a group of members of the public sector, along with foreign investors, to study the rules which were making difficult the access and permanence of foreign resources in the country. Progress has been announced by legal consultants, especially on the way the Central Bank controls the investments. The groups has also exerted great pressure on the Congress, by providing information to projects such as the ones referring to the new legislation of foreign capital, a new law concerning the industrial property, new software legislation and others. While the regulation of Mercosur is still being set up, one of the most important steps in that way was the enactment of the Resolution no. 1968/92 of the Central Bank of Brazil, which permits the realization of capital investments made by Brazilian persons or legal entities in the Stock and Commodities Exchange of the other countries, and the same goes for persons or legal entities of the other countries. Such investments can be made in North American dollars, in the currency of both countries involved in the investment. Such measure points, indeed, in the direction of a common market of stocks and commodities inside the Mercosur what would certainly fit to the intensification of the commerce.

Television Law

Television services, when not open to the general public, are not classified as broadcasting services, but as special services and do not fall within the restrictions of Article 222 of the Brazilian Federal Constitution, which requires ownership by Brazilian individuals (Agatiello, 1994). Depending on the mode of transmission (VHF, UHF, MMDS, cable and DTH), pay-TV services are subject to specific regulations. Despite the fact of not being classified as broadcasting, specific regulations on the different pay-TV modes still provide for limitations to the participation of foreign capital, as discussed below.

Special Service of Subscription Television: Decree No. 95,744/88, as amended by Decree No. 95,915/88, regulates the so-called Special Service of Subscription Television (TVA Service), which uses radioelectric waves (VHF or UHF) for transmitting codified signals to the subscribers. Exploitation of the TVA Service is only allowed to Brazilian national companies (the capital of which is held exclusively by Brazilian individuals). Such licenses are granted on a non-exclusive basis for a term of up to 15 years, subject to renewal for additional and equal periods.

Multipoint Multichannel Distribution Service (MMDS): The rules governing the MMDS are set out in Ordinance No. 43 of 10 February 1994, of the Ministry of Communication, which approved Norm 002194. This service is defined as the special telecommunications service which uses microwaves to transmit signals to be received, under a contract, in specific locations within the area of the service. Exploitation of MMDS service is allowed to legal entities having at least 51% of the voting capital held by Brazilian companies or Brazilian individuals domiciled in Brazil. Permission for the exploitation of the MMDS service shall be granted for a period of 10 years, renewable for equal periods, and on a non-exclusive basis.

Cable TV: The first attempt to regulate cable television services was made by Ordinance No. 250/89 of the Ministry of Communications which regulated the service of Distribution of Television Signals (DISTV). This service was conceived only for the distribution, by cable, of television signals within areas where such signals were not clearly received and operators were not allowed to generate their own programming. Licenses to exploit DISTV services are no longer being granted after the passage of specific cable legislation. As currently drafted, the rules restrict participation of foreign capital in this activity to no more than 49% of voting capital. Cable television is also being implemented in Brazil through agreements between public telephone services operators and private companies regarding the use of the telephone cable network for purposes of transmitting pay-TV programming.

Direct to Home Television Services (DTH): It may be provided by the use of satellite transmission services, which may be contracted with Embratel, the operator of Brazilian satellites Brasilsat I and II. Agreements with Embratel to obtain these services do not require any government license.

The participation of foreign investors in the Brazilian telecommunications industry has been a controversial issue over the years. In the past, telecommunications services were considered a key sector which should be reserved to the Brazilian Government (specially the public services) and/or Brazilian nationals (radio, TV etc.). In addition, the infomatics market reserve enforced until recently included the marketing of telecommunications equipment. With respect to current restrictions, the 1988 constitution reserves to the federal government, directly or through government controlled companies, the exploitation of telegraphic, telephonic, data transformation and other public services of telecommunication. The Brazilian Telecommunications Code defines public services as those executed by stations available for public correspondence, for use by the public in general.

Furthermore, the federal constitution provides that the government may, directly or indirectly, exploit any radio, sound, or image transmission activities. These activities may also be exercised by individuals (i) born in Brazil; or (ii) who obtained Brazilian nationality for more than 10 years, upon granting of a license from the government. The Brazilian Congress has been debating the lifting of the above restrictions, but no conclusion has yet been reached. Therefore, these restrictions are likely to remain unaltered for the time being. In addition to the restrictions of a constitutional nature, various portarias establish additional restrictions on a case-by-case basis. Whether such restrictions have an appropriate legal foundation is not a question we address here. The variety of restrictions should probably be viewed more as the result of historical processes than anything else. In general, some types of service have no restrictions, while others limit foreign participation to 49% (when speaking of voting capital), require that an operator be a "Brazilian company of national capital" (that is, one de facto and de jure under the control of persons domiciled in Brazil), demand state share control, or require that an operator be owned only by Brazilians.

Chile The economy of Chile has undergone a substantial transformation over the last two decades. Following the implementation of the free market economy, various governmental subsidies were substantially lowered, price controls gradually relaxed, average import tariffs reduced to reasonable levels, and extensive legislation was passed initially to attract and later to encourage domestic and, principally, foreign investments in Chile (Claro, 1993). Foreign investments may be brought into Chile either under the LOC or the Foreign Investment Statute (Decree Law 600). Under both systems, the foreign investors are granted access to the formal foreign exchange market for repatriate capital and profits. Capital invested thereunder may not be repatriated earlier than three years from the time the investment is made, but profits may be freely remitted abroad at any time at the discretion of each investor.

Certainly, Decree Law 600 affords the best legal protection available in Chile to foreign investors, as their rights and privileges are secured by an investment contract entered into with the Republic of Chile. These foreign investments are governed by Chilean law and are subject to the jurisdiction of Chilean courts. The LOC alternative available to foreign investors has traditionally been based only on an administrative resolution issued by the Central Bank and, consequently, is to some extent more vulnerable. Furthermore, Decree Law 600 grants to foreign investors additional protection, such as special protection against discriminatory treatment vis-a-vis domestic investors. Decree Law 600 provides that foreign investors and the local companies receiving investments are subject to the general provisions of law applicable to domestic investors and that no discrimination, neither direct nor indirect, may be made against them. Nevertheless, it provides that regulations may be enacted to limit the foreign investor's access to local financing.

On December 11, 1994, the prime minister of Canada and the presidents of the United States, Mexico and Chile announced their intention to pursue Chile's accession to the NAFTA (Gelkopf, 1997). However, the process of expanding NAFTA stalled when the American Congress refused to give President Clinton the fast track authority to negotiate with Chile. As a result, the Canada-Chile Free Trade Agreement was negotiated as a bilateral accord. The agreement was signed on November 18, 1996 and since then, several additional negotiating rounds have taken place. The Canada-Chile FTA includes two parallel agreements on environment and labor cooperation, modeled on the NAFTA side agreements. These side agreements reflect both countries' emphasis on increased cooperation and effective enforcement of domestic laws in these areas, while an exemption for cultural industries clearly excludes all forms of television from the FTA. These are the first agreements of this nature ever signed by the government of Chile.

The purpose of the Canada-Chile FTA is to eliminate most tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers on goods traded between the two countries. The Canada-Chile FTA calls for the immediate duty-free access for most industrial goods, which account for 80% of Canadian exports to Chile. Tariffs on many other industrial and resource-based goods will be phased out over a maximum of five years. While the Canada-Chile FTA will allow Chile to maintain existing capital control measures, it nevertheless prevents Chile from imposing more restrictive measures against Canadian investors. Most Canadian investors will no longer be subject to Chile's requirement that 30% of their capital remain in the country. This will give Canadian exporters an important advantage over their principal competitors in the Chilean market, including U.S., European and Asian suppliers, as well as Chile's regional trading partners. Total two-way Canada-Chile trade has increased dramatically since 1990, with shipments totaling $666 million in 1995, up 20 percent from the 1994 total assets of $553 million. Canadian investments in Chile have increased sharply in recent years and the cumulative total of actual and planned investments exceeds $7 billion. As Standard & Poor rated Chile as a BBB investment grade country, it celebrated the highest rating given to any country in Latin America today (Mexico followed with a BB+ rating).

Colombia Since the new constitution was adopted in 1991, deregulation of foreign trade and the opening to foreign investments have become priorities and the new regulations applicable to imports have eliminated the restrictions that were commonplace in Colombia to protect local industrial sectors (Urrutia, 1993). The system of prior import license and prohibited imports list have been virtually eliminated, and it is now possible to import freely most goods without obtaining prior governmental approval. The basic principle of foreign investment regulations is that foreign investors are entitled to equal treatment vis-a-vis Colombian investors. Accordingly, foreign investors can participate in all areas of the economy, with the exception of national defense and disposal of toxic waste product abroad. Foreign investors can own and control 100% of local companies and are not required to team with local investors. Foreign investments do not require prior governmental approval, with the exception of investments in oil, gas, mining and public services (power generation, distribution and transmission, basic telecommunications, water and sewage). Foreign investments must be registered with the Central Bank; such registration entitles the investor to repatriate yearly 100% of after-tax profits.

The government has recently implemented the law that created the Ministry of Foreign Trade, which is responsible for all matters having to do with imports, exports and other trade-related matters, such as bilateral and multilateral trade negotiations. The government is actively participating in bilateral and multilateral negotiations with other Latin American nations, with the United States, and with the members of GATT so as to ensure Colombian's active participation in the world markets. As a member of the Andean Pact, Colombia has also agreed to a new more liberal foreign set of regulations. In March of 1991, the Commission adopted Decision 291 that eliminates all prior restrictions to foreign investments within the region and authorizes the member countries to adopt their own specific rules concerning such issues as the rights accorded to foreign investors, the need to obtain prior approvals for an investment, the rules applicable to the resolution of disputes and the requirements concerning technical assistance and license agreements. Perhaps one of the most important aspects of Decision 291 is that it provides that all companies, whether national, mixed or foreign, operating within the region are entitled to take advantage of the trade liberalization programs, provided that their products fulfill the requirements of origin set forth in the implementing regulations of the Andean Pact.

Television Law Colombia is a founding member of the Agreement of Cartagena of 1969 (commonly known as the Andean Pact), a regional integration organization treaty that regulates a number of economic activities (Agetiello, 1994). However, telecommunications services have not yet been a subject matter of this integration policy. According to Colombia's legal system, international treaties ratified by Congress and duly promulgated by the executive branch are part of internal legislation and as such must be observed. Therefore, since the Andean Pact has already been approved and ratified, in the event the Commission of the Agreement of Cartagena issues regulations regarding telecommunications these shall be mandatory for all member parties to it, including Colombia.

For cable television services the broadcasting and programming, as well as the distribution of television signals, are subject matter of a concession agreement to be executed after a bidding process has been followed. Concession agreements may only be granted to national universities or companies duly incorporated under the laws of Colombia. This shall not be considered a restriction for foreign investment. Furthermore, in order to guarantee a free competition regime, and to prevent the abuse of a dominant market position by the concessionaires, no individual or company may be awarded more than 25% of the total amount of hours granted in concession on the same channel. Likewise, no individual or company may be awarded concession in more than one television channel. In order to protect national productions, any and all concessionaires are obliged to transmit national programs during at least 60% of the total amount of hours awarded.

Colombia has also been actively pursuing free trade agreements outside the scope of the Andean Pact, particularly with Venezuela. Venezuela and Colombia have entered into a bilateral trade agreement to adopt a common external tariff and a customs zone within two countries. The Colombian government has been actively negotiating with the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative in order to be eligible to take advantage of the benefits and incentives of the Andean Basin Initiative. Simultaneously, it has been negotiating with the United States, Mexico and Canada for an eventual integration into the North American Free Trade Agreement (Urrutia, 1996).

Ecuador On March 21, 1991, the Cartagena Agreement Commission issued Decision Nfl 291 containing a new common regime for treatment of foreign investments and on trademarks, patents, licenses, and royalties (Rumazo, 1991). As a general rule, a foreign person, whether an individual or company, does not require any previous authorization regarding its investment planned. Foreign investment is prohibited in the areas of: a) national defense and security; and b) radio, television (broadcasting), and press. Foreign investors may remit all profits abroad with no limits after withholding income tax and workers' profit sharing.

Mexico In the evaluation of Mexican lawyer Jorge Cervantes Trejo, over a period of approximately 25 years the regulation of foreign investment in Mexico has evolved from a nationalistic approach supported by state interventionist policies to a more open, competitive and pragmatic system promoting economic liberalism, foreign trade and investment (Trejo, 1999). The purpose of the 1973 Law to Promote Investment and to Regulate Foreign Investment was to avoid sale of already established Mexican companies to foreign investors, as well as to generally restrict foreign participation in Mexican companies to a maximum of up to 49%, although in most areas of economic activities the real intent was to keep foreign investors totally out of the Mexican economy, thus reinforcing the Mexican government's restrictive foreign investment policies of the time. But, as a consequence of the government's changing attitude towards foreign investment, on December 27, 1993 a new Foreign Investment Law (FIL) became effective.

Now, unless otherwise provided for in the FIL, foreign investment may now (i) participate in any proportion in the capital of Mexican companies, (ii) acquire fixed assets, (iii) participate in new fields of economic activity or manufacture new lines of products, and (iv) open, operate, expand and relocate existing establishments. Although the FIL initially reserved satellite communications and railroads exclusively to the Mexican state, amendments to Mexico's political constitution made after the FIL was enacted effectively repealed such reservations in favor of a gradual classification. The category of activities exclusively reserved to Mexican nationals and Mexican companies in which foreign investment cannot participate (3) include radio broadcasting and other radio and television services, excluding cable television services.

In the case of cable television, FIL establishes a maximum participation of 49%, except as otherwise provided for in international treaties. If there is a conflict between the provisions of the FIL vis-a-vis those in NAFTA, the latter prevails. And it is worth noting that NAFTA mandates that the Mexican government treat as Mexican nationals any such American and Canadian investors and their investments with respect to establishment, acquisition, expansion, management, conduct, operations, and sale or other dispositions. NAFTA also has extensive provisions which afford the U.S. and Canada, and thus their investors, a most favored nation treatment in everything from investment rules, trade in goods, market access, tariffs, rules of origin, customs procedures, energy, agriculture, government procurement, and dispute settlement procedures.

Television Law The basic telecommunications services are exempt from NAFTA (Agatiello, 1994). The 49% limit remains for local, long distance and international telephone services, cellular telephone services, and other common carrier services. The telecommunications chapter of NAFTA covers three areas of telecommunications law: public access, enhanced or value-added services and standard-related measures. The chapter, however, does not govern measures adopted by the parties to the agreement (Canada, the United States of America and Mexico) that relate to cable or broadcast distribution of radio or television programming.

The parties mutually ensure access to, and use of, any public telecommunications transport network or service on reasonable and non-discriminatory terms, and conditions and pricing based on economic costs. The enhanced or value-added services include telephone services that use computer processing applications that "act on format, content, code, protocol or similar aspects of a customer's transmitted information, provide a customer with additional, different or restructured information, or involve customer interaction with stored information." The NAFTA chapter specifies that application procedures for permits, licensing, registration or notification of such activities must be transparent (clear and without any discretionary powers of the authorities) and nondiscriminatory. Additionally, the application procedures may only require the information necessary to demonstrate financial solvency to begin providing services or information to determine conformity with applicable standards or technical regulations.

The standards-related measures are aimed at preventing discriminatory standards legislation and at developing a process to mutually accept test results from laboratories or testing facilities of the other parties. Finally, the parties ensure that any state-designated telecommunication monopoly will not act anti-competitively by, for example, allowing for cross-subsidization, predatory conduct, or discriminatory provision of access.

Paraguay A new constitution was approved in 1992, completing the restructuring of the state after 35 years of Stroessner's authoritarian rule (Peroni, 1993). In the first three years of the decade, 1,000 new investment projects were granted incentives for a total amount of investments exceeding $1 billion. The significant fact is that 40% was of foreign origin while the rest was Paraguayan capital in the form of reinvestment or new funds, which signaled confidence in the country and the process. Investment promotion laws provide a great range of tax and development incentives, without discrimination. Paraguay has negotiated a new OPIC Agreement with the United States which is the most liberal anywhere. It has ratified the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Convention, sponsored by the World Bank, and entered into various bilateral investment guarantee treaties with other countries, including Mercosur.

Uruguay The current democratic regime started in 1985, following 11 years of military rule. The three governments since then have aggressively pursued the opening of the economy and a more strict fiscal policy that aims to reduce the deficit and the chronic inflation that has plagued the country for over the last 30 years (Guyer, 1993). Foreign investors are freely allowed into Uruguay. Except in a few sensitive areas, there are no requisites whatsoever (previous license, permit, registrations, etc.) to complete. Importation and repatriation of capital and dividends are free. There exists a Foreign Investment Law, rarely utilized, that protects repatriation of capital and remittance of dividends in the case of the existence of foreign exchange controls (that have been unknown for almost 20 years). Overall, Uruguay has freedom of import and export and no exchange control regulations. It has signed with Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay a treaty creating in 1995 the Southern Common Market (Mercosur). In the territory, there are several Free Zones, ones being exploited by the state and others in private hands. Uruguay has further reduced import duties: as of January 1, 1993, they were 20%, 15% and 10%; for Mercosur countries, 6.4%, 4.8% and 3.2%.

Venezuela The telecommunication sector is regulated primarily by the Telecommunications Act of 1940 (the "Law") as amended in 1959. One-hundred-percent foreign-owned companies can be formed and remain as such except on reserved sectors, which basically are public services, mass media, telecommunications and internal marketing of imported goods. Decree 2.095, which describes the Common Regime for the Treatment of Foreign Capital and Trademarks, Patents, Licenses and Royalties approved by Decisions No. 291 and 292 of the Commission of the Andean Pact Agreement, expressly reserves television and radio broadcasting to local companies. There is no limit for international investment in the sector. There are only limitations for radio and television, except for Andean Pact nationals (Venezuela, Columbia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia), who have no limitations on cable TV (Pelaez-Pier and Lopez, 1996).

The services are provided through a concession granted by Conatel and the Law establishes a telecommunications tax at a range between 5% and 10% of the operational revenues. The television system by subscription is presently governed by the Regulation for the Exploitation of the Television System by Subscription contained on Decree 2.701 of January 11, 1989. In addition to the application of the above-mentioned Decree 2.701, the granting of the concessions within the television system by subscription is regulated by the analogous application of the rues contained in the Regulation on the Operation of Stations of Loud Radio Broadcasting. Considering foreign ownership limitations, the local companies are those which stock capital is owned in 80% by local investors, and the local investors of each one of the member countries of the Andean Pact Agreement can be either individuals or legal entities.

Television is reserved to local companies, capital stock of which can be up to 20% owned by foreign investors. The administration of the company can be performed only by nationals according to the above-mentioned decree. It should be emphasized that the companies which participate in the "television sector" reserved by law are those with the ability to emit the signal directly. For example, the signal sent from abroad or on a national level captured locally, with the capacity to reprogram and retransmit the signals commercially in the national territory via antennae, cable or any other means of technology, such as the companies of television by subscription. Therefore, the related television services can be performed by local, foreign or mixed companies. These services include technical and technological services, as well as administrative and commercial management.

Overall, price controls have been eliminated. Interest rates are being set by market forces. The differential exchange rate system has been eliminated and the bolivar (local currency) is floating freely. Import restrictions have been practically eliminated and a new customs system has been implemented (Bentata, 1989). With the new foreign trade policy Venezuela intends to favor the access of its products to global markets, rather than relying on schemes of economic integration, like the Andean Pact and the Latin American Association of Integration. In this sense, Venezuela is currently negotiating with the members of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) its adherence to such agreement.

Television Law The Andean Pact Common Provisions for the Treatment of Foreign Capital have liberalized almost all sectors of economic activity (Decree No. 2,905 of February 13, 1992). Telecommunications are completely open to foreign investment, except for television and radio services, which remain expressly reserved to local investment (Agatiello, 1994). This limitation, however, only affects the provision of the service as there exists no barrier to the supply of foreign equipment and technology to local companies that provide television and radio services. For a company to be considered local, at least 81% of its capital must be locally owned. Moreover, it is required that all companies applying for permissions and/or concessions to provide a telecommunications service must be domiciled in Venezuela. Besides the Andean Pact, other agreements signed by Venezuela also opened the door for neighboring entrepreneurs:

Agreement No. CJ/TA-159, complementary to the Basic Convention on Technical Cooperation signed by the Governments of Venezuela and Brazil on February 20, 1973: The complementary telecommunications agreement was signed in Brasilia on June 3, 1997. Its aims are to exchange experiences and/or services in the following areas: telephone demand, rural and mobile telephone service, domestic satellite communications; data transmission, basic plans for telecommunications and postal services, planning and control, technical planning, operational planning and supervision of implantation; standard systems for materials, equipment and services, organization of operation and research centers; implantation and consolidation of training systems; industrial and technological development and creation of new services.

Basic Convention on Cooperation for Development of Telecommunications signed by the Governments of Venezuela and Chile on October 10, 1990: Its aim is to procure the startup or continuation of the operation of telecommunications services in the following areas: telephone, telegraph, telex and other telecommunications services taking advantage of technical advances in this field.

Association of State Telecommunications Companies of the Andean Subregional Agreement (ASETA): The member states of the Andean Pact recently agreed to implement the Simon Bolivar Project. The pact aspires to launch its own satellite orbit in about five years. Venezuela is particularly interested in the promotion of the project and Conatel is directly involved in all technical and legal aspects. It is expected that this satellite will directly serve all the telecommunications service companies in the area.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub