Abstract

This article examines how the Houthi rebels in Yemen use tribal poetry as a propaganda platform to influence public opinion about the current war crisis in the country. By digitalizing Yemeni oral popular poetry, zamil, in the form of motivational war songs and YouTube videos, the Houthi militia group is able to attract young supporters, and publicly denounce Saudi airstrikes and the international sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council. While the study unpacks the hidden agenda of Houthi digital poetry and its multiple underpinnings, it sheds light on two important findings: 1) the understudied role of Houthi media campaign the way it’s been used as a digital weapon to advance Yemen’s Shiite militia movement, 2) how the Houthi use of social media revived a Yemeni poetic tradition, zawamil (plural of zamil) to disseminate a wide populous sentiment against the Saudi-led coalition and the United Nations Security Council in this civil conflict.

Introduction

For a long period of time, propaganda has been viewed as a powerful tool of influence and campaigning in the world. Recognizing the rhetorician’s ability to persuade and change ignorant masses, Plato attributes the degree of this influence to the “power of rhetoric”([1]). In Nazi Germany political messaging played a key role in the persecution of Jews, which had a significant impact on the Nazi rise to power before and during Adolf Hitler’s leadership of Germany from 1933 to 1945([2]).

Similarly, in the aftermath of the 2008 and 2020 US presidential elections, it became evident that political advertising on social media is a game changer, especially the way young opponents to the Republican party mobilized against the party and its position on issues pertaining to civil protests, police brutality, and racism. The long-standing use of political messaging in the former Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, the US, and more recently the Middle East and North Africa presents one of the most challenging issues in the study of global propaganda and national security (Ingram 2016).

The subtle use of media by militant groups, such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State (Da’esh), especially their ability to recruit foreign-born fighters to join extremist organizations in the MENA region, has already raised a warning call for counterterrorism experts and propaganda critics. The implications of this growing security concern have called for a thorough examination of propaganda tactics in war zones to further explore how a counter-terrorism media platform can dismantle the operative nature of digital extremism([3]). Nonetheless, studying digital counterterrorism in conflict zones, such as Yemen, Syria, and Iraq, still remains an underdeveloped area of research in propaganda and media studies. Extremist propaganda and the shifting nature of global media have become the “real battleground” for counterterrorism and national security in the aftermath of 9/11 and the rise of ISIS in Iraq and Syria (Briant 2015).

This article aims to address this shortcoming by showing how the Houthi militia continues to attain political power in Yemen by using media in a way that rapidly increases its online audience and network of supporters. The unprecedented rise to power of the Houthi militia rebels in Yemen presents a complex puzzle for political commentators and researchers working on the region. The overstated attention given by western and US media to the militia’s access to Iranian weapons has underestimated the important role played by Houthi social media, and its direct impact on expanding the militia’s political dominance in the country. By propagating a digitalized form of traditional Yemeni poetry, zamil, and encapsulating it with political messaging in the form of motivational YouTube videos and war songs, the Houthi militia has been able to expand its ideological project in Yemen in a short period of time.

Through a contextualized analysis of two zamil videos on YouTube, this article explores the overlooked role of Houthi media in the current conflict and calls upon media scholars and researchers to consider two important findings: 1) the underexamined role of social media use by Shiite militant groups in the region, and 2) how the revival of popular oral traditions, such as zamil poetry in Yemen, can be used as a powerful tool of digital influence.

Methodology

This study uses critical content analysis (CCA) as a qualitative approach that effectively assesses the impact of Houthi war poems and YouTube videos on the current geopolitical conflict in Yemen. As a research methodology, CCA provides textual, rhetorical, visual, and historiographic information that demonstrates the influence of media campaigns by militant groups and their online supporters. The criterion for selecting the studied Houthi media videos in this article focused on two important factors that explore the influential nature of Houthi media in the current crisis.

While the first criterion of selection focuses on how the Houthis have employed the uncontrolled spread of the coronavirus in Yemen as a war tactic against the Saudi coalition, the second one pays close attention to how this militia group has implemented the discourse of human rights and international law in their media campaign against the UN Security Council and its imposed sanctions on the Houthi leadership. To create a network of media supporters—as practiced by other extremist groups in the region such as Al Qaeda and ISIS—the Houthi rebels and their supporters have radically invested in the use of social media platforms that are widely accessed by the Yemeni youth.

Although there is a considerable amount of academic literature on online extremism and how extremist groups, such as Al Qaeda and ISIS, have used the internet for recruiting, funding, and propaganda purposes, the case of Houthi militias still remains an understudied area in the field([4]).

Most of the existing literature on militant groups and their use of social media focuses on Sunni groups. For example, in their seminal work titled Online Extremism: Research Trends in Internet Activism, Radicalization, and Counter-Strategies, Winter et al. (2020) provides an overview of how extremist groups use the internet and online tools by discussing major concepts such as cyber-terrorism and online radicalization through various types of media from websites, to password-protected forums, and encrypted messaging apps.

While the work by Winter et al. presents a generic framework for the study of how extremist groups employ online tools, it has yet to identify the rapidly-shifting nature of online extremism and its religious-political drivers, especially in the case of Shiite minorities in the Arab Gulf. Winter et al. provide some definitional key concepts and identifies general and specific tactics of internet use by extremist groups. However, the work pays little attention to how theological and geopolitical views drive and recalibrate the practice of online extremism.

In the last two decades, media and propaganda studies have developed to examine more closely the role of communication in the production of power, as well as the process of encountering power with truth through accountable and democratic forms of liberatory communications (Robinson 2019). Addressing a conceptual limitation in propaganda studies, Robinson proposes a new perspective that emphasizes “the wide range of actors involved in propaganda production and dissemination, including governments, academics, NGOs, think tanks, and popular culture, as well as the manipulative, and non-consensual modes of persuasive communication, including deception, incentivization, and coercion” (Robinson 2019, 1). The overemphasis on media itself and consensual modes of communication does not offer a productive framework for examining the multiple domains upon which propaganda is practiced and used as an influential tool of political communication. Propaganda studies, as Robinson points out, needs to expand its focus on the formal and consensual forms of communication that are often accessed through governments and political parties, and pay more attention to the new and invisible networks of communication that equally control and manipulate the production and circulation of political messaging.

Examining the role of online propaganda as practiced by the Houthis in Yemen does not only demonstrate the vital role of online media for militant groups, but also addresses an imbalance in the study of media and political communication in the production of power and political dominance in the country. The little attention given to what Baker et al. (2019a) term non-consensual organized persuasive communication by scholars in the field of media and propaganda studies, especially in the case of militant group’s media, shows the scale of influence played out by various institutions and entities in the production of propaganda, including news media, academia, and online popular culture (e.g. religious events and popular celebrations).

Despite the transformative nature of social media in conflict zones, the theoretical framework in the fields of propaganda and media studies still relies on western modalities of political messaging and democratic policymaking (Briant 2015, 3)([5]). Using these modalities of analysis to assess the use of propaganda in war zones in the Arab world does not offer a useful methodology to investigate how propaganda continues to influence public opinions about political legitimacy in conflict areas. It is the objective of this article to address the implications of this theoretical shortcoming by focusing on the case of Yemen, and how the Houthis utilize the power of digital poetry to perpetuate their political and religious motives on social media.

The first part of the study focuses on how the Houthis have employed the prevailing medical discourse around COVID-19 to influence public opinion about the intentional spread of the virus by their enemies. The first YouTube video analyzed in the first section of data analysis focuses on the politicized role of the global pandemic in the context of Yemen’s war crisis. The objective of the first section is to demonstrate how the rise and decline of infectious diseases in war zones is significantly impacted by geopolitical factors more than prevention efforts. The second part of this study pays more attention to the way the Houthis use propaganda strategies to formulate a politicized viewpoint about the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, and the questionable role played by the United Nations in this civil war.

The following sections of this article will examine the case of the Houthi militia and their use of internet tools to pinpoint the central and crucial impact of religious perspectives on the practice of media campaigning and online recruitment of young supporters. By analyzing the popular, political, and theological aspects of online zamil poetry disseminated by the Houthi militia on YouTube, this study aims to draw attention to the shifting nature of online extremism in a tribal and socio-religious context like Yemen. Parts I and II of the article will discuss some of the existing literature, and how this study advances some research findings and trends seen in the way other militant groups use online tools and social media.

How Houthi Media Revived Zamil Poetry in Yemen

Right after the Houthi rebels seized the Yemeni capital on September 21, 2014, major media outlets in Yemen were shut down and replaced with Houthi-run media([6]). This sudden media control resulted in the immediate silencing of opposing political perspectives in the country and the denial of journalist rights, and open media coverage in Houthi controlled areas. In the last five years, many human rights organizations have reported various incidents of torture and imprisonment of Yemeni journalists. In July 2020, Amnesty International launched a solidarity campaign to denounce the death sentences of four Yemeni journalists tried in a Houthi court in Sana’a. Despite these brutal measures against the practice of independent journalism and open media in the country, the Houthi leadership has taken steps to invest in the psychological impact of media propaganda on the Yemeni public.

After their ascendence to power in 2014, the Houthis started developing a strategic media plan to attract followers and supporters for their project in Yemen. This media strategy included the establishment of a media center tasked with the production of campaign audio messages, lecture tapes, religious songs, YouTube videos, and visual images that condemn the coalition’s airstrikes while praising the Houthi militia for protecting Yemen from western invasion. In less than five years, Houthi media productions became widely available to local and regional followers with a variety of media content, including expert interviews, political speeches, family shows, high production music videos, recitations of popular poetry, and other entertainment programs.

Zamil YouTube videos present one of the most popular and rapidly growing platforms of Houthi propaganda. These chanted war poems not only appeal to the broader public due to their motivational and melodic impact, but are also used to incentivize feelings of chivalry, victory, and independence. As a famous poetic genre in Yemen, zawamil (plural of zamil) are often sung in Arabic during weddings and festivities to celebrate highly regarded traits and cultural values. As an oral tradition, zamil poetry represents a form of identity-preservation and unique heritage that praises acts of bravery, kindness, and loyalty in Yemeni society. In tribal areas, zamil functions as a medium of reconciliation during local disputes and negotiations between opposing parties. Given the tribal nature of Yemen, the zamil form is also perceived as a community ritual that preserves the identity and unique traditions of the tribe and its alliances([7]). The revival of this unique poetic tradition in the current war has important implications for understanding how the Houthis are using social media as a weapon to inspire followers and weaken opponents.

Data Selection

For the purpose of this study, the researcher focused on the content of two Houthi YouTube videos that communicate a generic form of media propaganda for the Houthi militia in Yemen. The selected videos illustrate the embedded nature of Houthi media campaigns in the current crisis, and the type of geopolitical influence the group was able to attain through its social media productions. Since their ascendence to power and the fall of Sana’a in 2014, the Houthi administration has invested in the production of online propaganda messages, channeling the zamil song as military music that laments the former Yemeni government and their supporters.

The two YouTube videos analyzed in this study were produced by two of the militia’s poets and media producers: Isa Al-Laith and the Rebellious Boy of Ibb/ftā ib ālṯāʾr. Isa Al-Laith is the second composer of the Houthi YouTube zamil and is regarded as one of the most famous poets for the Houthi militia. Al-Laith has a significant presence on YouTube with more than 477,000 subscribers and 280 uploaded videos that openly praise the political and logistical advances of the Houthi militia in Yemen. The Rebellious Boy of Ibb is another content creator who has already produced a significant number of Houthi YouTube videos, exceeding one hundred uploads, and over one thousand subscribers. Although directed by the Rebellious Boy of Ibb, the first Houthi YouTube analyzed in this study was uploaded by Hannah Porter, a Yemen analyst working for the International Development firm DT Global.

Data Analysis

Part I: Coronavirus as a Media Weapon in Yemen’s Civil War:

Response to the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic and its global impact illustrate how various related themes and narratives were creatively used by militant and extremist groups in their online and media campaigns. In a recent study titled “Pandemic Narratives: Pro-Islamic State Media and the Coronavirus,” Daymon and Criezsi (2020) conclude that online pro-Islamic State networks have generated online content in a way to “appeal to a diverse audience, capitalize on a current event, as well as provide a space for community engagement and camaraderie in a time of social isolation” (1). In this study, the authors examine virus-related content posted in pro-Islamic state channels such as Twitter, Telegram, and Rocket.Chat from January 20 to April 11, 2020.

In a war-torn country like Yemen, COVID-19 has added an alarming level of human suffering caused by the lack of health facilities, shortages of medical supplies and a collapsed health system. But unlike other disease outbreaks in the country, such as malaria, cholera, and measles, COVID-19 has played an effective role in advancing the objectives of political propaganda for the Houthi rebels. The increased appearance of coronavirus-related Houthi zamil videos on YouTube shows how the Houthis are channeling pandemic-related messages for the purpose of advancing their political dominance. While COVID-19 YouTube videos appear to communicate prevention and health-related precautions to the public, they also propagate a political perspective that holds the Saudis responsible for the spread of the virus in impacted areas.

Coronavirus messaging on Houthi social media cleverly redirects public fear of the pandemic towards the risks of contagion that is allegedly initiated by their enemies in this civil war. The objective is to diffuse the fear of the virus in the Yemeni public towards the dangers of inflicted contamination and harm caused by the opposing party. As shown below in figure (1), the performer of this COVID-19 zamil video, “the rebellious boy of Ibb([8])” posts a COVID-19 video thumbnail to warn the Yemeni public about the detrimental risks of Coronavirus. The audiovisual and graphic production of this COVID-19 zamil focuses on coronavirus as a global pandemic, but the chanted lines of the zamil insinuate a feeling of fear towards the virus as a deadly tool that the Saudi coalition forces are plotting in their attacks on Yemen. The opening section of the zamil song informs the public about the pandemic by enlisting some precautions, including wearing masks, adhering to social distancing, and avoiding crowded areas. The first stanza reads as a list of prevention instructions that are more focused on the local spread of virus and its detrimental impact on Yemenis at large. The song mentions several mundane social practices in Yemen such as handshaking, crowded squares and the ritual of qat chewing([9]).

However, the rhythmic format employed in these precautionary statements create a conceptual harmony between the dangers of Coronavirus and how Yemenis can avoid its devastating grip. The first stanza comprises a COVID-19 warning that incorporates the literary elements of zamil poetry, including the repetition of the chorus and a rhyming scheme that harmonizes the content of the message in relation to the devastating nature of the coronavirus pandemic. Each line ends with a warning statement expressed in the phrase: “don’t let it infect you” or “so that it doesn’t infect you.” The first eight lines of the zamil read as follows:

lā tǧʿlh yntšr fyk- hḏā kwrwnā

This is corona, don’t let it infect you

hḏā kwrwnā wbāʾ qātl yṣyb ālmlāyyn - lā tǧʿlh yntšr fyk.

This corona is a deadly plague that has infected millions, don’t let it infect you

ẖḏ bālnṣyḥẗ wṭbqhā bkl ālmḍāmyn - li'ajl mā yntšr fyk

Follow the recommendations down to the last detail, so that it doesn’t infect you

hw yntql bāltṣāfḥ wāzdḥām ālmyādyn - lā tǧʿlh yntšr fyk

It spreads through handshakes and in crowded areas, don’t let it infect you

win kān lā bd mnhā fāltzm bālqwānyn - li'ajl mā yntšr fyk

And if it becomes necessary to go out follow the rules, so that it doesn’t infect you

wfy ālwqāyẗ ʿml ẖyry mn ālnhǧ wāldyn - li'ajl mā yntšr fyk

Prevention is a righteous deed in our religion and belief, so that it doesn’t infect you

wāḥḏr mkān āzdḥām ālnās wāhl āltẖāzyn - li'ajl mā yntšr fyk

Stay away from crowded areas and gatherings of qat chewing, so that it doesn’t infect you

wālbs ʿl ālānf kmāmẗ wlā tlms ālʿyn - li'ajl mā yntšr fyk

Wear a mask and don’t touch the eyes, so that it doesn’t infect you

Although the generic nature of these preliminary precautions in the first eight lines expresses a neutral stand towards the pandemic, they subtly prepare the listener for an explicit political position against the Saudi coalition in the context of the current crisis. The invocation of religion and righteous deeds in the first part of the song elicits an important element of distinction between what is “good” and “evil” from the Houthi perspective. In line six, the chanter claims that “prevention is a righteous deed in our religion and belief,” asserting how the Houthis view prevention as a religious duty that all Yemenis should abide by in order to stay protected from the deadly consequences of the virus.

The use of the Arabic phrase ml ẖyry mn ālnhǧ wāldyn reveals two distinctive aspects of the Houthi’s COVID-19 message in this zamil song on YouTube. The first one is the Houthi’s projected religious duty in limiting and controlling the spread of the pandemic in Yemen, and secondly is their claim to a righteous act of salvation (ml ẖyry) explicitly implied in the use of the Arabic word ālnhǧ (meaning path or way), which was highly emphasized in the early stages of the Houthi insurgency in Yemen([10]). The song begins with general prevention measures and recommendations, but it quickly moves to deliver an explicit political message about how the Saudi coalition embarks on a plan to worsen Yemen’s suffering through weaponizing the pandemic.

Unlike the first stanza and its purely didactic nature, the second part of this Houthi zamil inserts a propaganda message that is direct and vocal in its criticism of the Saudi coalition. The singer directly warns his listeners to be cautious of “the people of conspiracy” Āhl āltāmr by describing the Saudi coalition as a “congregation of devils” (Iʾtlāf ālšyāṭyn) that wishes to transmute this deadly disease to the Yemeni people. This warning is supported by an accusatory claim against the coalition in its attempt to spread COVID-19 as a war tactic that may weaken Houthi-controlled areas. The song chanter informs his audience that the coalition forces seek to “infect you with this disease,” thus demonstrating how the unprecedented spread of COVID-19 is used as a political weapon by the Saudis. Throughout this zamil song, the Houthi militia uses the uncontrolled spread of COVID-19 and its regional transmission as a propaganda tactic to support their political mission and fight against national and international forces. The song continues to support this claim by reminding Yemenis of a painful history of siege and war clashes between Yemen and the neighboring Saudi Arabia. The chanter revisits this history, saying:

wāḥḏr āhl āltآmr wālšyāṭyn - hm yštw ān yntql fyk

And watch out for those conspiring against us, the Satanic coalition, they want the disease to infect you.

mn ḥāṣrk wāʿtda ḍdk fy āʿwām wsnyn - yšty ālwbāʾ yntšr fyk

They are the ones who imposed a siege on you and attacked you for years, they want the plague to infect you.

By referencing the blockade imposed by the coalition forces on various parts of Yemen since 2014, the zamil attempts to insinuate a genuine appeal to the public by reminding people of the devastating consequences of the Gulf blockade. Since the start of the conflict, the Houthis have requested a complete lifting of the blockade, asking the international community to consider country’s urgent need for food supplies, medication, and humanitarian support for children and the elderly. The Saudi targeting of civilians, schools, and hospitals is intentionally mentioned here to reinstate feelings of anonymity and revenge against the Saudis and their unduly intervention in this civil conflict.

The last four lines of the zamil reaffirms that protection against COVID-19 and safety against the atrocities of the Saudi coalition is a religious duty, and part of the Houthis’ ideological belief. The rhyming structure of the song’s second half emphasizes the inhumane and expedient nature of the coalition forces as a “bench of tramps” (ṣʿālyk) and intruders that aim to harm Yemen. By repeating the chorus—lā yẖdʿwnā ālṣʿālyk or “the intruders will not trick us”—in this section, the song shifts its critique of the coalition to an attack on the inhumane expediency of the Gulf states towards Yemen and its geopolitical significance. The chanter reminds the audience that this is the safety of a nation, no longer a fractional dispute between a minority group and the local government:

"hḏh slāma wṭn wāltmn ǧzʾ mn āldyn، lā yẖdʿwnā ālṣʿālyk"

This is the safety of the nation and security is part of our religion, these intruders will not trick us.

"wkl mnfḏ ḍrwry lh rqāba wtqnyn، lā yẖdʿwnā ālṣʿālyk"

And every transit or entry point must be overseen and controlled, these intruders will not trick us.

"ly mnʿkm lā ymr ālšẖṣ mn dwn tḥṣyn، lkl ʿāyd lārāḍyk"

For your protection, anyone without immunity against the virus will not get through, for every person returning home.

"ly mnʿkm lā ymr ālšẖṣ mn dwn tḥǧyr، lkl ʿāyd lārāḍyk"

For your protection, those who have not been quarantined will not be allowed to pass through, for every person returning home.

Through the above-mentioned precautionary statements, the Houthis affirm their ability to implement the needed preliminary steps to protect the borders and any transit points between Yemen and Saudi Arabia. But the discourse of quarantine and immunity against COVID-19 is skillfully skewed here to propagate a Houthi view (not a health-centered perspective) towards the spread of coronavirus. While the Houthis claim to protect the country from the atrocities of the Saudi coalition and the conspiracy of inflicting this pandemic on Yemenis, this zamil song provides no practical solutions to some of the already infected areas, and how Houthi control of humanitarian assistance have in fact added a layer of complexity to the spread of COVID-19, in particular the difficulty of facilitating the process of vaccination in affected areas. Houthi propaganda towards the spread of Coronavirus in Yemen is a political move that aims to demonstrate to locals and the international community how the Saudi-led coalition is waging biological warfare against the people of Yemen.

Part II: Houthi Media Apparatus against the UN Security Council

The vital role played by the United Nations in Yemen presents another important focus on Houthi social media, and the militia’s attempt to mobilize against the United Nations Security Council, particularly its imposed sanctions on the Houthi leadership. The last four years witnessed an increase in media criticism initiated by the Houthis towards the United Nations and its Security Council. The Saudi-led coalition was formed on March 26, 2015, in response to calls from the president of Yemen, Abdurabbu Mansoor Hadi, for military support after he was forced out of his palace by the Houthi rebels in January 2015. Despite multiple efforts to implement peace and power-sharing agreements, as initiated by the United Nations, the Houthis decided to resort to military efforts and take over the capital and its vital government offices.

As an international organization mainly concerned with peace and security, the UN has taken the necessary steps to intervene as an intermediary between the two parties of conflict. The intervention of the Security Council in Yemen since the uprisings of 2011 resulted in failed endeavors followed by several resolutions that became detrimental to the political legitimacy of the Houthis in their unjustified fight against the legitimate government of Hadi. After five years of a continuous peace-making process in Yemen by the Security Council, the Houthi leadership started to express frustration and lack of trust in the UN mission due to, from their perspective, hidden objectives that only serve the agenda of the United States and the Saudi-Emirati coalition. Following the issuance of various resolutions, the chair of the National Convoy and the spokesperson of Houthis, Mohammed Abdulsalam, noted that “the United Nations is not serious about stopping this invasion and releasing the imposed sanctions on Yemen”([11]). The spokesperson further accused the organization of committing vicious war atrocities against children by refusing to enlist Saudi Arabia as a major violator of children’s rights.

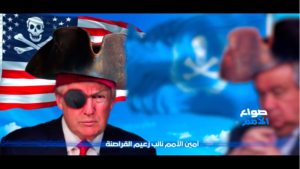

In a Reuters TV interview conducted in Sana’a in July 2016, the Houthi spokesperson elaborated further to say that: “America is condemning itself and confirming that it is not thinking about stopping the aggression (..) and that it stands behind the prolongation of the war and the exacerbation of the humanitarian crisis”([12]). In a tweet posted by another major leader of the Houthi group, named Mohammed Ali Al Houthi, the Security Council and its resolutions are openly scrutinized for “confirm[ing] a deal that aims to restore António Guterres, as a Secretary-General the way Ban Ki-Moon was also forced to remove Saudi Arabia from the disgrace list given its war crimes in Yemen.”[13] The Houthi tweet supports this claim by showing photos of violently-killed children due to the use of weapons supplied by the United States and Britain. The visual captions (see figure 2 below) used in this zamil video authenticate some of these accusations in which the Secretary-General of the United Nations Security Council, António Guterres, is shown wearing a pirate hat with a pirate-themed logo centered on the UN flag.

The visual orchestration of this caption sarcastically substantiates the political view encompassed in the Houthi tweet to express strong disapproval of US support for the Saudi coalition. Artistically alluding to this disapproval, the producer of this zamil video creates a watershed image of Donald Trump (see figure 3 below) named in Arabic as the Pirate General and projected as the main source of support for the biased UN resolutions and Saudi attacks against Yemen.

Figure (2) A Houthi video caption displaying on the right-hand side the Secretary-General of the United Nations Security Council, António Guterres, as the deputy pirate with a pirate-themed logo centered in the UN flag.

Figures (3) A video caption showing former US President Donald Trump as the Pirate General backing the Saudi-led coalition against Yemen, positioned right to the foreshadowed Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres. Image Source: Houthi YouTube video “The Leader of Pirates”/zʿym ālqrāṣnẗ([14]).

According to a report published by UNICEF in June 2020, at least 3,153 children have been killed and more than 5,660 children injured in Yemen since early 2015([15]). Houthi accusations about the violent killing of innocent children in Yemen point to Saudi airstrikes and publicly criticize the use of destructive weapons supplied by the US and Britain. But these accusations mainly blame the United Nations for failing to demonstrate to the international community the deadly nature of these unlawful airstrikes on children, women, and the elderly. For example, the targeting of schools by Saudi airstrikes has exceeded 240 since 2015, and it is ironic that the UN has verified half of these aerial attacks, according to their annual report on Yemen. While the UNICEF report points to a serious escalation of war violations against children and their safety in Yemen, it fails to blame either party for such atrocities:

Nowhere is safe for Yemen’s children. More than 4.3 million are estimated to be in direct danger due to a wide range of threats—from death and injury in attacks, to being forced to take part in the fighting. Since March 2015, the United Nations has verified that 3153 children have been killed and 5660 have been injured. That means that as each new month of fighting passes, on average another 50 children die, and more than 90 more are wounded or left with potentially life-long disabilities. Many more are left with lasting psychological damage. The actual numbers of those killed and injured—including cases that the UN is unable to independently verify due to access or other restrictions—are likely to be much higher”([16]).

The violent airstrikes and military operations launched by the Saudi-led coalition have been widely criticized by many human rights organizations. UNICEF reports details of some of the deadly consequences of these airstrikes, but it does not say much about the severe damage caused by the use of seven types of cluster munitions made in Brazil, the US, and Britain. In 2017 and 2018, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented the use of Brazilian cluster munitions that resulted in the unlawful killings of 21 civilians, and wounding of more than 74, in major populated areas in Yemen. The Saudis have acknowledged the use of these fatal weapons in Yemen, but also claim the right to their lawful use according to war laws set by the Geneva conventions([17]).

Another propaganda tactic the Houthis use in their media productions is their reliance on the discourse of human rights, international law, and the blatant claim that the Security Council is an organization that works to serve the objectives of western powers rather than the people of Yemen. The Houthi media war against the coalition and their use of “cluster munition” against children employs the discourse of international humanitarian law to expose the UN’s failure to hold the Saudi-coalition and their allies responsible for their crimes.

Uploaded to YouTube on Jul 21, 2020, the producer of the zamil, Shabl Shaker, demonstrates to the international community how the Security Council—as an organization responsible for maintaining international peace and security in accordance with chapter VII of the UN Charter—has failed to appropriately use its influence over governments of member states. The producer of the zamil uses this media production to expose the Security Council’s unjust decisions and arbitrary resolutions, showing the way the UN has mandated its sanctions on the Yemeni people, while being oblivious to the war crimes of the Saudi coalition.

The Conspiracy of the Nations’ Measuring Cup

In a rhetorical move that invokes the powerful Quranic story of Prophet Yusuf (Joseph in the Bible) with his wicked brothers, the producer of this zamil video ironically gave this Houthi YouTube song the title: “To the United Nations and Pirates’ Leader: ‘The Nations’ Measuring Cup.” As shown in figure (4) below, the linguistic choice of the zamil’s subtitle, “The Nations’ Measuring Cup,” in Arabic ṣwāʿ ālumam, alludes to the significance of the measuring cup in Prophet Yusuf’s story and the way the United Nations has allegedly accused the Houthis of wrongdoing in Yemen.

Figure (4): Another video thumbnail image of the Houthi zamil “To the UN and Security Council,” featuring a young Houthi fighter positioned in the center of the Security Council meeting with its 15 members.

In the Quranic context, section 12 verse 69-79, the king’s measuring cup (ṣwāʿĀlmalk) is the object that Prophet Yusuf secretly hid in his younger brother’s bag. After provisions were provided to Prophet Yusuf’s brothers, the soldiers of the palace accused the caravan of stealing the king’s measuring cup. This allowed Prophet Yusuf to start searching his brothers’ bags first and end the search by returning the cup. This planned setup allowed prophet Yusuf to use the king's stolen cup as an excuse for keeping his younger brother from the company of his other cruel brothers([18]). This Quranic story is invoked in the zamil to explain how the UN has orchestrated a setup, similar to prophet Yusuf’s use of the King’s missing cup, in order to lawfully grant the Saudi-led coalition legitimate reasons for attacking Yemen and its people.

Written by Bassam Shanie and performed by Issa Al Laith([19]), this Houthi YouTube zamil presents a well-formed critique of the UN Security Council as a responsible party for Yemen’s suffering and hardships. The title of the video is dedicated to the Security Council and to the pirate leader, referring to the major sponsor and guardian of the coalition, the Saudi king Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud backed by the former US president, Donald Trump. The words and phrases used in the zamil are carefully selected to disseminate a narrative about western injustices and biases towards the war in Yemen.

The first measure of UN support was crystalized in its advancement of the Gulf Cooperation Council Initiative, which was signed on November 23, 2011 in Riyadh. Despite the short-lived success of the Initiative, the UN remained active in its attempt to restore peace and security in Yemen through negotiations and the implementation of various resolutions; including 2014 (2011), 2051 (2012), 2140 (2014), 2216 (2015), and 2511(2020)([20]). The first sanctions were imposed in February 2014. It mandated an asset freeze and travel ban on listed individuals. A sanctions committee was also convened, tasked with the job of implementing these sanctions. For example, in Resolution 2014 (2011) under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, the UN Security Council stated the following before enlisting the details of its demands:

Recognizing that the continuing deterioration of the security situation and escalation of violence in Yemen poses an increasing and serious threat to neighboring States and reaffirming its determination that the situation in Yemen constitutes a threat to international peace and security([21]).

While Resolution 2216 (2015) appears to focus on the implementation of peace and security in Yemen, it also underlines the alarming scale of “serious threat” to neighboring countries, and the importance of maintaining the safety of these significant geopolitical players in the region. Through this zamil, Houthis denounce the way the UN Security Council has legitimized the destruction of a whole nation with its biased resolutions, which according to the Houthis has allegedly contributed to the loss of millions of people in Yemen.

Addressed to the UN Security Council and the Saudi King (described as the Pirate leader), the song reveals the biased nature of the Council’s decisions and resolutions, implied by the figurative use of the king’s missing cup in prophet Yusuf’s story in the Quran. The first section of the zamil calls the reader to further understand how the Security Council has intentionally implanted UN rhetoric and its unjust resolutions (the measuring cup) as a logistical weapon to block international humanitarian support to Yemen. According to the Houthi narrative in this UN-criticizing zamil, the ‘measuring cup’ or ṣwāʿ ālumam is referenced as an “enforced mechanism” that aims to justify Saudi war crimes. The song illustrates how the UN resolutions have consequently resulted in preventing international vessels of sustenance to enter Yemen during challenging times. However, there is also a complete disavowal on the part of the Houthis to admit how their control over important land checkpoints, seaports, and the implementation of new taxation rules have exacerbated the suffering of people as well.

Martin Griffiths, the Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for Yemen, has repeatedly expressed concerns about the need to remove Houthi-created obstacles disabling the importation and delivery of fuel, food items, and medical supplies to war-impacted areas in Hudaydah and other provinces. The taxation in particular constituted some of the major obstacles to the arrival of international humanitarian aid and support to the country in recent years([22]). The direct reference to the imposed UN sanctions in the zamil distorts some of the facts that have contributed to the suffering of Yemeni people in this war. While the Houthis accuse the UN of “pleasing and empowering” the agendas of the Saudis, there is no explanation why this civil war between two opposing Yemeni parties became a regional conflict, involving the GCC, the US, the UK, and Iran. Acknowledging the devastating nature of this violent war, the Houthis ironically call the UN Secretary-General “the deputy of the Pirate leader,” therefore referring to the loyal position the Security Council holds for the guardian of the Saudi-led coalition, king Salman Bin Abdul Aziz and the military support initiated by the United States.

Figure (5) A visual trait that aims to mobilize viewers by illustrating how the Houthi zamil is “a sacred platform that shakes the thrones of tyrants.” Image Source: Houthi YouTube Shabel Saba’a

For the Houthis, UN loyalty to the Saudis, in the name of international laws and resolutions, is nothing but a form of “inhumanity,” described as the merciless brutality of vicious hyenas feeding on a severely bleeding wound: Yemen. By invoking UN-cited terms such as “human rights” (ḥqwq Insān) and “the honoring of the dead” (krāmẗ myt) as implied in the idea of human dignity and peace in the UN laws, the zamil draws attention to the depreciation of human life by the Saudi-led coalition, and the UN as an international ally in this war. The first part of the zamil uses pity to make an appealing case for portraying the Saudis and the UN Secretary-General as Pharaohs([23]), lacking a true understanding of human rights and dignity.

Following a critique of the Security Council resolutions and their detrimental impact on the Yemeni people, the zamil shifts its tone to show how faith and reliance on God is the only path to true victory and salvation in Yemen. The performer of the zamil turns to the power of faith by stressing how God’s support is “the real support and his defense is the real defense” against the partial decisions of the UN and the brutal attacks of the Saudi-led coalition. However, unlike the opening of this disapproving assessment of the UN Security Council’s active engagement in the Yemeni crisis, the ending section of the zamil instigates sentiments of victory by reviving a feeling of patriotism and religious commitment to the slogans and motives of the Houthis in this civil war. The invocation of patriotic feelings and religious sentiments towards the end of the zamil indirectly supports the Houthi viewpoint, while attempting to delegitimize the UN sanctions, and the military operations launched by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Advancing the viewer’s patriotic views as informed by religion, the writer of the zamil accentuates the fact that, “unlike other pampered nations, the people of Yemen are guided by knowledge and the process of noble selection rather than the mandated polls of election.” This claim is informed by an important religious belief for the Houthis. The deliberate use of the Arabic term āliṣṭfāʾ meaning “noble selection” in English, in the above-mentioned line points to the importance of religious leadership for the Houthis as opposed to the western idea of electoral voting implied by the Arabic term ālāqtrāʿ or “elections” in English.

As Zaydi Shiites, the Houthis describe themselves as Ansaru Allah which roughly translates to “the Partisans of God.” This God-given vocation is attained through their presumed linkage to Zayd bin Ali, the great grandson of Ali Ibn Abi Taleeb, prophet Muhammed’s cousin and son-in-law, whom they regard as “a model of pure caliph”([24]). Revering the martyred Zayd in his revolt against the Ummayds, the Houthis believe that their inspiring leader and founder of their movement in Yemen, Hussein Badreddin Al-Houthi, is also a progeny of Zayed bin Ali, thus making the Houthi struggle a divine mission, ordained by God, rather than social movements and democracy. But this proclaimed religious status is questionable for various reasons.

Although the Houthis claim to attain inspiration from religion, as publicly expressed in their slogans, their major source of power is political dominance. The reference to “noble selection” as a purely divine trait candidly celebrates the highly regarded status of the Zaidi imams (Sada in Arabic) in Northern Yemen([25]). Claiming their descent from the prophet Muhammed, these imams have always been concerned with their unwelcomed position in the new republican state. Since the collapse of the Mutawakili rule and the rise of liberal ideology in the country, Zaidi groups have attempted to hold a recognizable position in the new republic of Yemen. In his analysis of this debated religious issue for the Houthis, Charles Schmitz concludes:

In the liberal period of the 1990s, some of the Sada emerged to search for a place for themselves in the republic. They formed two political parties, al-Haqq (Truth) and Ittihad al-Quwa al-Shaabiyya (Union of Popular Forces). Al-Shabab al-Muminin (Believing Youth), the predecessor of Ansar Allah, was meanwhile founded by Hussein al-Houthi to revive Zaidi tradition in the face of effective proselytizing among the young by Saudi-backed Wahhabis and local Salafists. But it was the attack of the Saleh regime on al-Shabab al-Muminin that propelled the movement to the fore of Yemeni politics([26]).

The long-standing tensions between Zaidi imams and the leaders of the new republic in North Yemen date back to the demise of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom, which ruled the country from 1918 to 1962 and resulted in the overthrow of Zaidi spiritual leaders with support from Egypt’s president Gamal Abdul Nasser and the proponents of Arab nationalism. The deposing of the Mutawakkilite rulers and the decline of Zaidi religious ideology in Yemen carries some of the driving motivations for the Houthis’ current movement and their revolt against Saleh’s government.

In the wake of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, the chief of the Houthi movement in Yemen, Hussein Badredine Al-Houthi, was assassinated. Al-Houthi founded the “Believing Youth” movement([27]) in 1990, and was the first Yemeni politician to denounce the government’s security measures in the province of Sa’dah, following his famous anti-American cry: "Death to America. Death to Israel. Curse the Jews. Long live Islam” in the Grand Mosque of Sana’a. As an elected member of the Yemeni parliament, Hussein criticized President Saleh’s western-influenced rule of Yemen, especially Saleh’s support of the United States’ “War on Terror” and its drone program targeting Al Qaeda members in the country in response to the 9/11 attacks. The overstated emphasis on divine guidance and faith in the Houthi zamil aims to emotionally stir the viewer’s religious empathy towards western oppression and government corruption at the cost of concealing the true motives that informed the movement in light of important regional developments, including the collapse of the Ottoman empire and the early establishment of the Qasimi dynasty in the Arabian Peninsula.

The current conflict in Yemen is conspicuously rooted in some of the theological values that have fueled the Zaidi monarchy of the Rassids (also known as Banu Rassid) and their ascent to regional power as early as 1500. The political aspirations and religious slogans of the Houthi outcry in Yemen are conceptually consistent with the characteristics of aristocratic Zaydism that flourished during the medieval era. By advancing old theological and political agendas in the name of a divine mission superficially mobilized by the language of social justice and minoritization, the Houthi movement is able to gain a wide public appeal among the young generation that has failed to rethink introspectively the genesis of the movement as outlined on the margins of history. Despite its trendy technological outfit, as shown in the audiovisual montage of these Houthi YouTubes, there are embedded political and theological viewpoints mainly expressed through the glorified language of Islamic victories and regional battles. The deft reference to historical incidents aims to centralize the Houthi political perspective in the name of religious triumph. The ending line of the zamil reveals the intense nature of such seemingly religious views, shrewdly stated in the following line: wlā bd mā ylqa ālyhwd ālṣhāynẗ nhāyẗ yhwd ābnāʾ qryḍẗ wqynqā, which translates to “and eventually the Zionist Jews will have the same end as the Jews of Gureida and Qaynuqa’a”([28]). It would be erroneous to assume that the above-cited ending of the zamil condemns Zionism through this anti-Israel proclamation.

Researchers and political scientists writing about the political implications of the Houthi cry([29]) (the Sarkha meaning scream in Arabic) may reach such a conclusion based on the hostile language directed towards Jews and the Jewish state([30]). However, the objective of this anti-Israel curse is a bit more subtle than it appears to be. Through this proclaimed curse, the Houthis are able to restore an incident of triumph against the Jews of Madinah. By decontextualizing this incident and sidelining Jewish-Muslim coexistence in the Arabian Peninsula before and after the death of the prophet of Islam, the ending of the Houthi zamil pulls the audience’s heartstrings to only advance the Houthi agenda in a way that marginalizes the severity of this civil conflict and its growing regional scale.

Conclusion

Zamil poetry is widely circulated in Yemen today in the form of digitized war videos and songs that easily instigate sentiments of sovereignty, chivalry, and victory in audiences. Through creative digitization of Yemeni folk poetry as YouTube war videos and songs, the Houthi rebels are able to expand their political dominance and influence various public opinions ranging from the recent spread of coronavirus and the failed role of the United Nations in this civil conflict, to the ongoing intervention of the Saudi-led coalition. The political and religious embeddedness of Houthi messaging in these YouTube videos and war songs shows media critics the need for a more productive conceptual approach to the study of digital propaganda in war zones. The transformative nature of Houthi media and its adaptive use of online tactics highlight the important role of political digital influence in the MENA region. In a short period of time, the Houthis were able to revolutionize their reliance on social media to attract supporters and online followers. The change in Yemen’s media following the rise of Houthis to power in 2015 offers a compelling case for the importance of studying digital propaganda during wartime, especially for Shiite militia groups in the region. The overstated emphasis on assessing Houthi access to militaristic support from Iran in western media and academic circles have overlooked the militia’s skillful use of media to attain political control and to attract an online appeal towards the Houthi movement in Yemen.

Appendix A:

YouTube Video: “Ansar Allah Zamel, Coronavirus, May 2020”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mj1kmSgpYQA&t=110s&ab_channel=HannahPorter

هذا كورونا - لا تجعله ينتشر فيك

This is Corona - don’t let it infect you

هذا كورونا وباء قاتل يصيب الملايين - لا تجعله ينتشر فيك

This Corona is a deadly plague that has infected millions- don’t let it infect you

خذ بالنصيحة وطبقها بكل المضامين - لأجل ما ينتشر فيك

Follow the recommendations down to the last detail, so that it doesn’t infect you

هو ينتقل بالتصافح وازدحام الميادين - لا تجعله ينتشر فيك

It spreads through handshakes and in crowded areas, don’t let it infect you

وإن كان لا بد منها فالتزم بالقوانين - لأجل ما ينتشر فيك

And if it becomes necessary to go out follow the rules, so that it doesn’t infect you

وفي الوقاية عمل خيري من النهج والدين - لأجل ما ينتشر فيك

Prevention is a righteous dead in our religion and belief, so that it doesn’t infect you

واحذر مكان ازدحام الناس وأهل التخازين - لأجل ما ينتشر فيك

Stay away from crowded areas and gatherings of qat chewing, so that it doesn’t infect you

والبس على الانف كمامة ولا تلمس العين - لأجل ما ينتشر فيك

Wear a mask and don’t touch the eyes, so that it doesn’t infect you

Appendix B:

مونتاج زامل (( صواع الأمم )) عيسى الليث - 1441هـ || كلمات بسام شانع | #الحصار_جريمة_حرب

“UN Embargo is a War Crime# Houthi Zamil ((The Nations’ Measuring Cup,))’ Issa Al Laith 2020| the words of Bassem Shan’aa.

هنا شعب ما بين ألف دولة وسلطنة تفرّق دمه يا مجلس الأمن باجتماع

Here is a nation between a thousand countries and a sultanate.

You disperse its blood, O Security Council, in a meeting!

ملايين الأنفس كنها غير كاينة تحاصر وتعزل منقطع ذكرها انقطاع

Millions of souls made to be dead,

intentionally besieged and isolated to be invisible.

صواع الأمم مدسوس في كل شاحنة وما تحجز إلا من لقت عنده المتاع

The measuring cup of the UN is cleverly tucked in every truck And they only sanction those with bare human substance.

بغبة سنين القحط واشد الأزمنة تصادر سفن سد الرمق حيلة الصواع

With the desire to inflict more hardships and years of famine, Ships of sustenance and human aid are taken away in the name of the ‘measuring cup.’

تداهن وتتغذى الوحوش المداهنة على أكباد وقلوب المساكين الجياع

Pleasing and feeding flattering monsters on the livers and hearts of the hungry poor.

أمين الأمم نايب زعيم القراصنة والإنسانية هيئة لوحشية الضباع

The Secretary General of the UN is the deputy leader of the pirates. And their humanity is nothing but an assembly of hyenas' brutality.

ماشي حقوق إنسان عند الفراعنة ولاشي كرامة ميْت في عالم الضباع

The oppressing Pharaohs (the Saudis) know no human rights, and there is not even dignity for the dead in the world of hyenas.

لنا رب ما يغفل ولا تأخذه سِنة ولاشي خسارة في سبيلة ولا ضياع

We have a lord who neither forgets nor ignores, There is no loss in his way, nor forfeiture.

وهو وحده المانح ومنه المعاونة وتأييده التأييد ودفاعه الدفاع

He alone is the Giver and the Sustainer, And His support is the real support and His defense is the defense.

تضيق الدنى وتضيق وتضل فاهنة سكينة وعزة ومجد وشموخ وارتفاع

This world can be difficult and constrained, but remains demeaning, there is always tranquility, dignity, glory and uplifting.

وشعب اليمن غير الشعوب المدجنة يقوده علم والاصطفاء غير الاقتراع

Unlike other pampered nations, The nation of Yemen is guided by knowledge and noble selections rather than elections.

شموخه سما فوق السماوات ثامنة يماني يتوه الكون في صدره الوساع

His glory is the eighth above the heavens, a Yemeni undefeated by the world with his wide chest.

ومن يعتصم بالله هو بايمكنه وشعب اليمن باينتزع حقه انتزاع

And whoever holds fast to God, He will support, And the people of Yemen can forcibly snatch their rights

على الله وحده لا سواه المراهنة وصدق التحرك والتولي وإلا تباع

On God alone we rely, He is the true inspiration of movement, leading and following.

ولا بد ما يلقى اليهود الصهاينة نهاية يهود ابناء قريضة وقينقاع

And eventually the Zionist Jews will face the end of the Jews of Gereida and Qaynuqa.

Bibliography:

Amnesty International, “Yemen: Global Solidarity with Four Journalists Sentenced to Death.” Accessed July 20, 2021.

Porter, Hannah. “Ansar Allah Zamel, Coronavirus, May 2020.” YouTube video, 1:57, May 13, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mj1kmSgpYQA&t=110s&ab_channel=HannahPorter

مونتاج زامل (( صواع الأمم )) عيسى الليث - 1441هـ || كلمات بسام شانع | #الحصار_جريمة_حرب

Bakir, V., E. Herring, D. Miller, and P. Robinson. 2019b. “Deception and lying in politics,” In Oxford Handbook on Lying, edited by J. Mauber. London: Oxford University Press.

Blumi, Isa. 2018. Destroying Yemen: What Chaos in Arabia Tells Us about the World. California: University Press.

Briant, Emman Louise. 2015. Propaganda and Counter-terrorism: Strategies for Global Change. Manchester University Press.

Caton, Steven. 1990.“Peaks of Yemen I Summon”: Poetry as Cultural Practice in a North Yemeni Tribe. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Daymon, Chelsea and Meili Criezis. 2020. “Pandemic Narratives: Pro-Islamic State Media and the Coronavirus.” CTC SENTINEL 13, no.6 (JUNE 2020):26-32.

Human Rights Watch. 2017. “Yemen Cluster Munitions Wound Children: Brazil Should Stop Producing Banned Weapon, Join Ban Treaty,” Accessed June 18, 2021.

https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/17/yemen-cluster-munitions-wound-children

Plato. 1952. Plato's Phaedrus. Cambridge: University Press.

Porter, Hannah. 2020. “A Battle of Hearts and Minds: The Growing Media Footprint of Yemen’s Houthis,” Gulf International Forum, June 1, 2020. https://gulfif.org/a-battle-of-hearts-and-minds-the-growing-media-footprint-of-yemens-houthis/

Robinson P. 2019. “Expanding the Field of Political Communication: Making the Case for a Fresh Perspective Through ‘Propaganda Studies.’” Front Commun. 4:26. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00026.

Shirer, William. 2011. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Zawamel Ansar Allah Lelmontage. 2020. “UN Embargo is a War Crime# Houthi Zamil ((The Nations’ Measuring Cup,))’ Issa Al Laith 2020|the words of Bassem Shan’aa.” YouTube video, 2:13, Jul 18, 2020.

UNICEF. 2020 “Yemen Five Years On: Children, Conflict and COVID-19.” Accessed June 18, 2021.

Winter, C., P. Neumann, A. Meleagrou-Hitchens, M. Ranstorp, L. Vidino, and J. Fürst. 2020. “Online extremism: Research trends in internet activism, radicalization, and counter-strategies.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 14(2), 1-20.

([1]) In Phaedrus, Plato remarks that rhetoricians have specific motives and a different understanding of “truth.”

([2]) See, William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, (New York: Simon and Schuster), 2011, 29-33.

([3]) See Emman Louise Briant, Propaganda and Counter-terrorism: Strategies for Global Change, (Manchester University Press 2015),185-222.

([4]) There is an existing body of literature on how anashid and war poems are used by ISIS and Al Qaeda members in in the MENA region, but not specifically on the Houthi militia and their employment of digital poetry in the current war crisis in Yemen. For example, Elisabeth Kendall has written on the importance of Jihadist poetry for Yemeni tribes, and how poetry is used a weapon of Jihad in Yemen. In a similar fashion, Nelly Lahoud has presented rich research insights that explore the role of anashid and poetry in Jihadism. For more details, see her books titled, The Bin Laden Papers (Yale University Press 2022) and The Jihadis' Path to Self-destruction, (Hurst 2010).

([5]) Like Briant, a number of media scholars have pointed out that the focus on the post-war period in mass media studies has mistakenly viewed propaganda as a “key characteristic of modern democracy."

([6]) Almasirah (meaning journey in Arabic) was the first channel founded and owned by the Houthi group even before the battle of Sana’a and their rise to power in 2014 and 2015. The TV channel is headquartered in Beirut, Lebanon and located next to Hezbollah’s Al Manar TV.

([7]) For a detailed account of the sociopolitical significance of tribal poetry in North Yemen, see Steven C. Caton, “Peaks of Yemen I Summon: Poetry as Cultural Practice in a North Yemeni Tribe” (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1990).

([8]) The producer of the video describes himself, in Arabic as فتى إب الثائر, which translates as “the rebellious boy of Ibb.” Ibb is a city located in the Northern part of Yemen, it’s the capital of Ibb governorate which is about 117 km northeast of Mocha and 194 km south of the Yemeni capital, Sana'a. Since the start of the Yemeni war, many news media have described Ibb as “the hotbed of infighting in Houthi-controlled areas in Yemen.” For more information, see https://acleddata.com/2019/10/03/inside-ibb-a-hotbed-of-infighting-in-houthi-controlled-yemen/.

([9]) Qat chewing is a social habit in Yemen that features social gatherings and daily meetings between chewers of qat.

([10]) For more information see: Bruce Riedle, “Who are the Houthis, and why are we at war with them?” Brookings, December 18, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2017/12/18/who-are-the-houthis-and-why-are-we-at-war-with-them/

([11]) For more information see: Reuters, “Yemen's Houthis Say U.S. Is Prolonging War by Imposing Sanctions: TV,” U.S. News, March 3, 2021, https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2021-03-03/yemens-houthis-say-us-is-prolonging-war-by-imposing-sanctions-tv

([13]) See RT’s article: الحوثيون: الأمم المتحدة تعمل منصة لصالح الدول الكبرى وتصنيفاتها غير محايدة

([14]) Figures 2 and 3 are from the same video source:

"ālḥṣār ǧrymẗ ḥrb mwntāǧ zāml (( ṣwāʿ ālumam )) ʿysā āllyṯ - 1441hـ || klmāt bsām šānʿ |"

([15]) For more details about the content of the report and its statistics, refer to the following link: https://www.unicef.org/mena/sites/unicef.org.mena/files/2020-06/EMBARGOED%2026%20June%200001%20GMT_Yemen%20five%20years%20on_REPORT.pdf

([17]) For a more detailed account of how cluster munitions have been used by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, refer to https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/17/yemen-cluster-munitions-wound-children

([18]) The Qur’anic verses that explain Prophet Yusuf’s action in this part of the story include the following section:

“And when they went in before Joseph, he took his brother unto him, saying: Lo! I, even I, am thy brother, therefore sorrow not for what they did. (69) And when he provided them with their provision, he put the drinking-cup in his brother's saddlebag, and then a crier cried: O camel-riders! Lo! ye are surely thieves! (70) They cried, coming toward them: What is it ye have lost? (71) They said: We have lost the king's cup, and he who bringeth it shall have a camel-load, and I (said Joseph) am answerable for it. (72) They said: By Allah, well ye know we came not to do evil in the land and are no thieves. (73) They said: And what shall be the penalty for it, if ye prove liars? (74) They said: The penalty for it! He in whose bag (the cup) is found, he is the penalty for it. Thus we requite wrong-doers. (75) Then he (Joseph) began the search with their bags before his brother's bag, then he produced it from his brother's bag. Thus did We contrive for Joseph. He could not have taken his brother according to the king's law unless Allah willed. We raise by grades (of mercy) whom We will, and over every lord of knowledge there is one more knowing. (76)

([19]) The YouTube video shows the names of the zamil writer and performer this way:

أداء عيسى الليث Ādāʾ ʿysā āllyṯ

كلمات بسام شانع klmāt bsām šānʿ

([20]) For a detailed account of the latest UN resolutions against Yemen, refer to

https://www.un.org/press/en/2020/sc14121.doc.htm.

([21]) See page 3 of Security Council resolution 2216 (2015) [on cessation of violence in Yemen and the reinforcement of sanctions imposed by resolution 2104 (2014)]. The full version of resolution 2216 (2015) is available at the following link: https://www.refworld.org/docid/553deebc4.html

([22]) For more details on these obstacles, see the UN report published on March 21, 2021 https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sc14470.doc.htm

([23]) The zamil includes the plural form of Pharaoh or ālfrāʿnẗ, which refers to the name of an ancient ruler in Egypt known for his tyranny and oppression. The same name is mentioned in the Quran and many biblical references use the phrase “the Pharaoh of the Oppression'' to refer to the persecutor of the Israelites. For more information about the biblical version of the name, see the English Bible Dictionary: https://st-takla.org/bible/dictionary/en/p/pharaoh-oppression.html

([24]) For more details about Zayd bin Ali and the religious doctrine of Zaidiyyaism in Yemen, see https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2017/12/18/who-are-the-houthis-and-why-are-we-at-war-with-them/

([25]) The Arabic word سادة “Sada '' refers to descendants from Prophet Muhammed’s family, and in the context of North Yemen the term denotes the revered status of the Zaidi Imams, who ruled Yemen for a long period of time, before the establishment of the Republic of Yemen in 1962. In the twelver Shia belief, any descendants of the prophet’s family are regarded as divinely appointed leaders. For example, the leading figure of the Houthi movement in Yemen, Abdul Al Malik Al Houthi, is often referred to by his followers as “al saeed” / السيد, a religious leader or imam descended from Prophet Muhammed’s family.

([26]) See Charles Schmitz’s account of Zaidi Sa'adah in Yemen in his 2015 BBC report titled “The Rise of Yemen’s Houthi Rebels,” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-31645145.

([27]) “The Believing Youth,” al Shabab al-Mumanin in Arabic, was established in the province of Sa’adah with the aim of educating young people about the Zaydi branch of Shiite Islam, which had ruled Yemen for centuries and was oppressed by the new republic state after the Yemeni revolution of 1962.

([28]) The names Gureida and Qaynuqa’a refer to two Jewish tribes that lived in the city of Medina in Saudi Arabia and according to many historical resources these two Jewish communities were expelled by Muslims for breaking an important treaty known as the Constitution of Medina that time.

([29]) The Houthi cry (also known as the Sarkha / scream in Arabic) expresses the movement’s slogan: “God is great, death to America, death to Israel, curse on the Jews, victory to Islam.”

([30]) For more details, see Waleed Mahdi’s commentary on the Houthi cry in a book chapter titled “Echoes of a Scream: US Drones and Articulations of the Houthi Sarkha Slogan in Yemen,” in Cultural Production and Social Movements After the Arab Spring: Nationalism, Politics and Transnational Identity, eds, Eid Mohamed and Ayman El Desouky. (London: I. B. Tauris, 2021), 205-221.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub