In the wake of the Arab uprisings, journalists, activists, and scholars coupled creative with revolution (or dissent, protest, resistance) to describe political graffiti, rap, art, and video. Distinguished institutions, from the Prince Claus Fund of the Netherlands to the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, lend the concept gravitas. The notion of “creative revolution” has a nice resonance. It is hard to think of a negative meaning to “creative,” and “revolution” acquires a positive sense when directed against loathed autocrats. “Creative revolution” appeals because it conjures up ordinary people standing up against oppression and doing so artfully. This language echoes rhetorical commonplaces about the uprisings being “nonviolent” and “nonideological.” But this nebulous notion is tricky. “Creative” seems to designate an artistic object, an item involving color, shape, melody, words, something that is supposed to stir feelings in us. Adding “creative” leaves a residual category of noncreative resistance. Can we really distinguish one from the other? Can we restrict creativity to aesthetics? Is using lemon juice to mitigate the pain of tear gas not creative? Are silent vigils not ingenious? Is using a cooking pot as a helmet to protect your head from police projectiles not imaginative? Are three persons riding a moped to a makeshift clinic, wedging the wounded and unconscious between the bodies of two unimpaired activists, not inventive? For the pairing of creativity and rebellion to convey anything beyond a vague notion of hip, nonviolent struggle, it requires a definition that reaches beyond aesthetic concerns to incorporate actions that are physical and symbolic, violent and peaceful.

The notion of creative insurgency accomplishes just that. Insurgency means “rising in active revolt.” The noun comes from the eighteenth century, through French and Latin, in which insurgent means “arising,” from the verb insurgere, from in, which means “into” or “toward,” and surgere, which signifies “to rise.” Insurgency connotes more activity and intensity than dissent, resistance, protest, but less upheaval than revolution. The uprisings cannot be described as revolutions, perhaps with the exception of Tunisia, for even if leaders fell, their regimes have survived, and the overall system of political, economic, and cultural repression endures. Insurgency captures two tempos of action—radical and gradual—that this book identifies and explains. Insurgencies include regular successions of low-grade ambushes punctuated by occasional outburst or major attacks, and insurgents are typically not recognized as worthy adversaries: Arab despots dismissed them as traitors and terrorists, as germs, rats, or snakes threatening the body politic. Insurgency also undermines claims that the Arab uprisings were nonviolent—rebels have torched buildings, hurled stones, clashed with police—and recognizes that violence can be symbolic, verbal, physical, and structural. Creative insurgency combines two types of violence that overlap and sustain each other: the kind of violence inflicted with words, songs, and images and the one wreaked with fire, stones, and rifles, acting in tandem to dislodge dictators. Doing so summons a broader sense of creativity, germane to art and aesthetic concerns, but also to other kinds of revolutionary action: chanting slogans and burning your body, spraying graffiti and tending to the wounded, circulating jokes and building barricades. If creativity, in the sociologist James Jasper’s definition, is an “extreme form of flexibility,” then few instruments can be as creative as the human body. People use their bodies for aesthetic expression, but also in actions that are creative in physical or political ways.

***

What are some attributes of creative insurgency?

Creative insurgency is willful, planned and deliberate. Rarely is it spontaneous. Mural street art is a laborious endeavor. Even stencils, executed in quick squirts of paint through precut templates, take a great deal of honing. Graffitists first cut stencils from cardboard, then practice intently to test different kinds of paints and materials (cardboard? Laminated paper?) and try out several colors. When I visited on graffiti artist in a decrepit suburb of Beirut, I noticed on the walls of his home studio half a dozen iterations of a famous stencil that I had tracked around the city. Some were crisp, others murky. In one, spilling paint oozed several inches below the stencil itself; in another, too much paint was spattered, deforming the stencil’s design. The artist used yellow on a dark wooden surface in the entrance, but daubed dark blue right on the off-white wall of the living room. Thorough preparation also applies to sloganeering, an intricate social process with formal and informal elements involving a division of labor between slogan composers who toil away from the limelight and charismatic slogan leaders who perform in public.

Creative insurgency is not an external expression of internally preformed emotions, ideas, or beliefs. It expresses rebellion as much as it shapes it. Spinoza understood human nature as a fluid fusion of body and soul, and Herder believed that what we feel and what we express are intricately connected, that “the human being who expresses himself is often surprised by what he expresses, and gains access to his ‘inner being’ only by reflecting on his own expressive acts.” This is fundamental: Creative insurgency gives voice and shape to revolutionary claims as much as it prods insurgents to always reassess their aspirations and identities. As a theory of power, creative insurgency rejects the distinction between mind and body, persuasion and compulsion, symbolic and physical violence.

Creative insurgency is a social process. It is not the work of an individual artistic genius toiling alone in obscurity. Arab revolutionary figures became iconic precisely because they represent something bigger than themselves. The bodies of Mohamed Bouazizi, Khaled Said, and Aliaa al-Mahdy refract various kinds of repression and resistance. Figures you will encounter is Qahera, Captain Khobza, and Sprayman embody widely shared fears and desires. Revolutionary practice itself is collective: some well-known artifacts are the work of groups of people, dedicated, coordinated, often anonymous. Several activists toiled to create and maintain the “Kullina Khaled Said” Facebook page; a handful devised the Top Goon web series. Kharabeesh (doodles), creator of the Journal du Zaba satirical videos, is actually a Jordanian group. Others include Mona Lisa Brigades in Egypt and Asha‘b Assoury ‘Aref Tareqoh (The Syrian People Know Its Way) in Syria. Like other kinds of human artfulness, creative insurgency arises out of social interaction.

Creative insurgents fuse familiar and foreign, old and new. These ingenious activists graft new meanings onto recognizable symbols. Bouazizi’s self-immolation echoed Kurdish self-immolators and Palestinian suicide bombers. A decades-old poem by Abdul Qassem al-Chabbi, a gifted Tunisian poet who dies in 1934, inspired revolutionaries in 2010. Revolutionary digital finger puppetry is a heady mix of ancient and avant-garde, wielding familiarity with puppetry, presidential speeches, torture sessions, and reality television. Firestorms of controversy surrounding naked activism are rooted in century-old quarrels over art and nation and contemporary polemics about feminist art and activism. It is in the volatile fusion of past and present that creative insurgency flourishes.

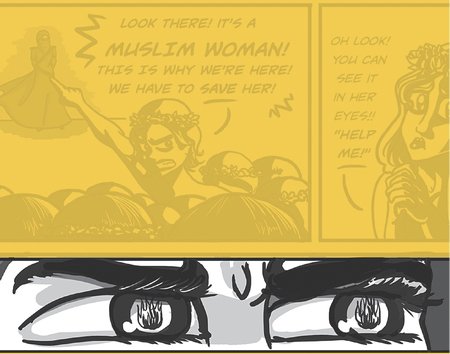

Hell-bent on projecting local struggles globally, creative insurgents use resonant symbolism. They draw on a historically deep repertoire in order to achieve a geographically wide resonance. Egyptian muralist Alaa Awad used neo-pharaonic motifs, and Franco-Tunisian artist el-Seed found inspiration for “calligraffiti” in Islamic calligraphy. To reach a worldwide public without undermining local authenticity, these artists must reconcile local rootedness with global attention. Though swaddled in local politics, revolutionary art seeks to extend its reach, but it cannot allow global political or commercial forces to absorb it completely, for then it ceases to be art. This is a burning issue because the uprisings have spawned a global renewal of Arab art. When activist-artists exchange the grit and peril of the streets of Cairo and Damascus for the comforts and safety of European residential fellowships, American museums, and Gulf galleries, they enter transnational circuits of art, money, and politics. Many artist-activists of the Arab uprisings are now refugees in Amsterdam and Paris, Beirut and Berlin, Sharjah and Stockholm. With the rise of the “creative-curatorial-corporate complex,” risks of selling out are as big as the rewards of fame.

Finally, creative insurgency plays a documentary role that broadens the impact of revolutionary action. Consider how digital images expanded the reach of Bouazizi’s self-burning from a desolate town in the Tunisian hinterland to global attention, and how activists used a panoply of media to spread their message to the world. Creative insurgency celebrates heroes, commemorates martyrs, and sustains revolutionaries. It depicts bodies murdered, maimed, or tortured and contributes to an evidentiary chronicle of political abuse. It triggers debate and contributes to a vast, crowd-sourced archive of revolutionary words, images, and sounds. Artistry is important, because the ability to attract a public depends on what the literary critic Michael Warner called the “differential deployment of style.” Creative insurgency, then, consists of imaginatively crafted, self-consciously pleading messages intended to circulate broadly and attract attention: forms in search of visibility.

***

How does creative insurgency unfold?

The Naked Blogger of Cairo identifies two modes of creative insurgency, radical and gradual. The radical mode of Burning Man entails embodied, life-or-death revolutionary action, like self-immolation. This type of insurgency occurs in one-time outbursts. It is violent and spectacular. The survival of the human body itself is at stake. Radical deeds are life-threatening actions spawned by deadly conditions. The radical mode is crucial because it is a direct confrontation with the ruler, an open challenge to his sovereignty. In contrast, the gradual mode of Laughing Cow subverts the norms of sovereign power. It trespasses its boundaries by launching symbolic attacks at the ruler. Body imagery is central to this type of revolutionary action, and a peculiar aesthetic of peril and deprivation underscores corporeal vulnerability. The gradual mode is distinctive in the incremental and cumulative ways it chips away at power. It can be seen in revolutionary humor. Through symbolic inversion, such actions pull the powerful down to the level of the powerless.

The radical and gradual modes entwine. They fuel and shape, prod and pull each other. Gradual rebellion expands prerevolutionary dissent in Egypt, Syria, and Tunisia: double-entendre parodies, ambivalent art, and allegorical theater that autocrats encouraged, tolerated, or manipulated. In contrast, radical creativity is a no-holds-barred, high-risk, high-reward gambit. Sporadic radical actions fuel waves of gradual infractions that reverberate widely, setting grounds for the next radical gauntlet. The violent outburst of Bouazizi’s self-immolation inspired graffiti, memorials, videos, and slogans that in turn galvanized other radical actions. Unfurling with different speeds, cadences, and visibilities, radical and gradual activisms mesh in time and space. Naked Blogger mixes Burning Man and Laughing Cow and muddies distinctions between them. By inviting both moral opprobrium and threats of physical oblivion, al-Mahdy’s digital nude selfie had immediate rhetorical and physical consequences. Many acts of creative insurgency are hybrids of radical and gradual.

Together, radical militancy and gradual activism set in motion a contest between three kinds of body—classical, heroic, and grotesque—that induces status reversals. Classical bodies, like the statues of antiquity, are bounded, hard, erect, and dominant. They are high-perched bodies that dictators give to themselves via ceremony, pomp, and ubiquitous statues in heroic poses—arms raised basking in the adulation of their subjects, hands clasped and a bold forward gaze contemplating a bright future, captions extolling contrived heroic deeds. But classical bodies are also immobile, cold, and distant, disconnected from the people and impervious to their struggles. Had you visited Egypt, Syria, or Tunisia before the uprisings, you would have been unable to avoid the gaze of one or another statue, portrait, or monument glorifying the heroic body of the leader. Classical bodies pretend to be heroic bodies, but that cloak is flimsy.

Heroic bodies put themselves in harm’s way for noble, larger-than-self causes. They burn with the fire of righteous indignation and just rebellion. Consumed by the oppression meted upon them and others by the dictators’ self-declared classical bodies, heroic bodies are leaders at the forefront of change. Because of their willingness to lead rebellion, heroic forerunners are vulnerable. They attract a lion’s share of repression. But in their corporeal vulnerability, heroic bodies are a living witness to injustice and a breathing clamor for dignity. In contrast to bounded classical bodies of despots, insurgent bodies are heroic when they overcome their own boundaries. Some are accidental heroes. Samira Ibrahim, a young Egyptian woman, stumbled into activism after Egyptian authorities subjected her to a “virginity test.” This kind of state-sanctioned rape, like self-immolation and torture, violates bodily frontiers—thresholds of human dignity. Others achieve heroic status by a willful act, like Bouazizi, or by tragic happenstance, like Khaled Said, the Egyptian youth fatally beaten by the police. Heroic bodies tend to be young, but some are not, though compared to dictators gone to seed, they look youthful indeed.

Heroic bodies turn classical bodies into grotesque bodies. The Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin developed the notion of the grotesque body to refer to the debasement of what is usually honored, respected, or feared. This is accomplished through contrarian imagery from human and animal anatomy. My usage of the term in a lethal, revolutionary situation differs from Bakhtin’s, who applied it to the sanctioned context of carnival, but the difference is a matter of degree.

Many believe that the revolutions stalled because revolutionaries agreed on the necessity to eject dictators but failed to articulate an alternative political vision. But as Annabelle Sreberny-Mohammadi and Ali Mohammadi wrote in their classic study of communication in the Iranian revolution, “All revolutionary movements are creative evolving processes that write their own scripts.” Claims that the Arab uprisings failed because the insurgents focused on spelling out what they were against but were unable to articulate a set of positive demands—what they were for—miss the point of creative revolutionary expression altogether. To the question, Did the uprisings really founder? the stories that follow offer glimpses of a momentous transformation of human bodies, from subjugated individuals to revolutionary persons. In fact, creative insurgency’s most vital contribution is the way it stitches personal and political identities together and transforms both in the process. Creative insurgency is the harbinger of a new sense of self. The body is crucial to the rise of revolutionary selfhood, for it is the body that connects ideas to action, mobilizing and directing symbolic and material resources, in a cycle of radical and gradual acts that drive creative insurgency. Revolutions cause total upheaval that puts values, beliefs, and norms up for grabs. Creative insurgency is a response to a “revolutionary situation,” a set of circumstances that compel individuals to congeal into collectives that challenge the status quo. In The Creativity of Action, the German sociologist Hans Joas describes a “situation” as “the ability of the body to move and communicate in an innovative way.” For this to occur, “creativity must be enacted through both the body and the social system of meanings that recognizes the action as different from the norm.” Indeed, “creative action unifies the mind and body in doing something perceived as different.” In the cycle of creative insurgency, a revolutionary situation spawns novel expressions that incubate new identities that fuel rebellion, which spurs a new understanding of the self, over and again.

Self-renewal and the birth of a new political identity depend on extracting sovereignty from the body of the ruler. Creative insurgency is the sum total of processes through which revolutionary subjects extricate themselves from the body of the sovereign in order to create a new body politic. During the Arab uprisings, activists opened symbolic wedges between the dictator’s two bodies, inserted levers in that space, and pushed with all their strength to widen the chasm to the breaking point between the nation and the dictator’s body. Creative insurgency, then, is hell-bent on wrenching body politic from body natural to rescue sovereignty form the grip of the tyrant and give it to the people.

The Naked Blogger of Cairo follows a straightforward organization. Though scholars of politics, art, culture, media, and the Middle East have plenty to sink their teeth into, general readers should find the stories compelling and instructive. Part II explains the radical mode of creative insurgency, and Part III, the gradual. Though the first draws mostly on Tunisia and the second on Egypt, both analyze patterns that exceed single countries. With the two types of activism explained, Part IV features exemplary cases of creative insurgency that show how the human body extends itself through the revolutionary public sphere, mixing radical and gradual insurgency. Several stories in the third part come from Syria and some from Egypt, but the analysis has a broader purview. Grappling with issues of sexuality, citizenship, and nationhood through a comparative analysis drawing form Egypt, Tunisia, global activism, and the French Revolution, Part V, home to the book’s title essay, probes a blind spot of the king’s two bodies doctrine by exploring the politics, aesthetics, and ethics of naked activism. Essays in Part VI take up debates about contemporary art triggered by creative insurgency, evaluate counterrevolutionary currents, including the sinister rise of Daesh, and give a final assessment of the body in revolutionary politics.

From The Naked Blogger of Cairo: Creative Insurgency in the Arab World by Warwan M. Kraidy. Copyright 2016 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub