Much attention has been given to the role of electronic media in organizing recent protests in Egypt, particularly the ability of a group known as the “April 6 Youth Movement” to attract 70,000 members to a Facebook group in support of a general strike planned for April 6, 2008. Print media, however, have been relatively understudied despite their importance as a shaper and reflection of elite opinion and their role in influencing public perceptions of the protests. There was a dramatic discrepancy among Egyptian papers in how the strikes were described, and so a comparison of how Egypt’s official and independent newspapers framed the 2008 protests makes a fascinating case study in how social movements and their opponents seek to present advantageous versions of events. How this effect occurs is relevant to the study of both social protest movements and the ways in which authoritarian regimes deal with opposition.

Some may challenge the importance or influence of print media in Egypt; roughly half of the population of Egypt is illiterate and it is generally only elites who are the primary consumers of print media. While I am hesitant to overstate the influence of newspapers, to discount the message that print carries entirely is short-sighted. It can be argued that the goal of the competition over framing is precisely to influence those very elites who, after all, are generally those wielding political power. While this study examines newspapers published immediately after the April 6 strikes, the argument presented here should be generalizable to other forms of media such as television, or to any other medium in which we find a competition to establish an accepted interpretation of events – the dominant frame.

Framing social movements

Theorists of media framing hold that how news is presented will impact the way it is understood. At the most basic level, “frames” are organizing principles that are “socially shared and persistent over time, that work symbolically to meaningfully structure the social world.”[i] Framing “recognizes the ability of a text … to define a situation, to define the issues, and to set the terms of the debate.”[ii] How a given issue is framed exerts a powerful influence in how the public perceives the various elements involved. Thus, a government has a vested interest in making sure that it is represented favorably in the media it controls. How, then, do independent media outlets or protesters seek to challenge the frames advanced by government media?

Charles Tilly proposes that all social movements wish to be seen as demonstrating four key traits, to which he assigns the acronym “WUNC.” They are: worthiness (being seen as dignified, e.g. showcasing mothers or veterans), unity (using common symbols or slogans), numbers (creating a large headcount, filling or emptying spaces) and commitment (braving bad weather or resisting repression or opposition).[iii] Any deficiency in one category can be compensated for by another, but the total effect needs to be present to form a convincing demonstration. Just as popular protest movements and sympathetic media seek to display these four traits, their opponents in government or competing movements seek to neutralize or deny them.

What does it mean to “deny” these displays? In examining the papers under consideration, we see what McLeod and Hertog term “marginalizing” frames. These include violent crime or property crime which base stories around violence or vandalism and emphasize efforts of police to restore order, which protestors are depicted as damaging.[iv] Of particular note is Khalil Rinnawi’s work on the strategies Israeli media employed to delegitimize Palestinian participants in the al-Aqsa Intifada. These include drawing most information from official sources, which tend to emphasize the state’s efforts to restore law and order, portraying protestors as a threat to society which places the group outside the state and paints their actions as damaging to others (possibly including the readers), legitimizing the actions of the dominant group (for example, arguing that police were provoked), balancing the coverage in favor of the dominant group, and “blaming the victim” by implying that police are simply responding to protesters’ infractions.[v]

In many ways, these are extensions of Tilly’s WUNC characteristics; blaming the victim, emphasizing disorder and threats, and balancing coverage to favor the dominant group all attack the worthiness and commitment of the protestors. It is, indeed, a full reversal: instead of “resisting repression” by standing up to the police, governments seek to portray protesters as inciting police. Instead of being labeled as “organized students” or otherwise, protesters instead become “disorderly youth.”

Snow and Benford offer the concept of “resonance” to describe the effectiveness or mobilizing potency of proffered framings. Resonance hinges on credibility and salience: for a frame to be credible, it must be both empirically credible (“the sky is green,” no matter how well framed, will not resonate well) and come from a credible source. For a frame to be salient, it must fit into pre-existing narrative conceptions and values held by the readers.[vi] This is far more difficult to measure, but presents an avenue for future research.

Findings

I spent April 6, 2008 walking around downtown Cairo. There were only a handful of the usual cars on the road, and many shops and merchants were closed. Few pedestrians were outside, and a fair number of students were absent from the American University in Cairo – although classes were held as normal. Instead of the normal traffic, tens of State Security trucks sat parked at every intersection, with battalions of riot police and plainclothes thugs standing near the major squares. These tactics put a stop to any major protest; a group of three students that began yelling slogans in Midan Tahrir were immediately pushed into a van and driven away.[vii] Although there were not any large organized protests, the State Security response and empty streets indicated that the routine had been interrupted. This is precisely the arena of news media – to add detail and meaning to a situation outside the realm of readers’ experience. With this perspective, let’s consider the coverage of Egypt’s opposition and independent papers: the newcomer al-Badeel, Ibrahim Eissa’s al-Dostour, and al-Masry al-Youm.

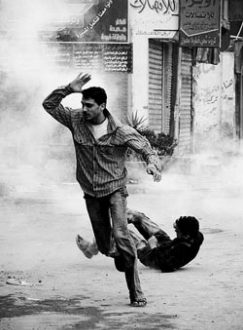

On April 6, 2008 al-Badeel led with the unusually large headline, “Wind of strikes sweeps over Egypt.”[viii] Below that ran three rows of main headlines: “Demonstrations and arrests and empty streets in every district,” “Demonstrations ignite in al-Mahalla [a factory town north of Cairo] … [State] Security meets them with tear gas canisters … more than 2000 demonstrators at the Lawyer’s Syndicate,” and “Random seizing of citizens … arrest of tens of members from Kifaya, al-Nasseri, al-Ghad, and al-Karama [opposition political parties].” At the same time, the front page was filled with pictures showing protestors on a building, one waving an Egyptian flag, surrounded by police. The caption read, “Security besieging demonstration at Lawyer’s Syndicate on Ramsis Street yesterday.” Other captions read “A procession of the students of Helwan University yesterday,” “Children in Alexandria carrying Egyptian flags” and “half-empty lecture hall at the University of Mansoura.” Two other photographs show empty streets and their captions indicate that they were taken in the middle of the day – when streets would normally be very crowded.

The main article on al-Badeel’s April 6 front page also features a telling interview with a police officer stationed in Tahrir Square, which reads in part:

Reporter: What’s the news of the country, sir?

Officer: The country is tranquil, as you see here, and totally secure…everything is good, thanks be to God.

Reporter: The country is “tranquil” or has been “made tranquil”? [i.e. pacified by force]

Officer: Enough with that al-Badeel talk, I know you all. The country is good…

Reporter: Why was the statement from the Ministry of the Interior so violent, saying ‘we will strike [the protestors] with an iron fist’?

Officer: that isn’t violent or anything … the law must go on so that you yourself will feel secure. If we did not uphold the law, you would be afraid for yourself, for your house, and you wouldn’t be walking in the street.

The choices on display in al-Badeel’s coverage combine to produce a positive impression of the movement and paint the protests as effective. In this case, we see protestors behaving patriotically, carrying the Egyptian flag, and identified as lawyers, students, etc. – not as “hooligans.” Their unity is displayed by actions such as marching, displaying signs, and standing together. The paper also emphasizes numbers, quoting 2000 as attending the protest at the Lawyer’s Syndicate and giving exact numbers of workers at companies that had participated in the strikes. Images serve to reinforce this perception, by displaying empty streets (large numbers absent – i.e. participating in the strike). Meanwhile, images of protesters always filled the frame; there was no empty space around them, which reinforced the impression of numbers and action. Al-Badeel’s coverage also highlighted the commitment of the protesters by mentioning the tear gas, random arrests and police brutality they endured for their participation. In other words, all four elements of Tilly’s WUNC are on display in al-Badeel’s coverage; not just on the front page, but carrying through the four page spread the paper dedicated to the April 6 protests.

Al-Masry al-Youm went to press with the somewhat unusual headline “Strikes – all parties are satisfied.” The subheadline reads: “Mahalla ignites – State security puts down protests in Cairo – The opposition succeeds without the Muslim Brotherhood.” The article goes on to explain that each party felt that they had achieved their objective: the organizers had achieved what looked like a strike, and state security had kept the upper hand throughout the day. The main text is located above the fold, with a large image of a bloodied protestor captioned “citizens of the city of Mahalla carrying an injured friend after confrontations with police.” Below the fold is, as normal, occupied by advertising. Their coverage continues inside on pages 3-6 (the normal page 2 “news roundup” was not interrupted), with pages 3 and 4 forming a full spread with large text on the bottom reading “Egypt in state of strike.”

In al-Masry al-Youm’s April 6 coverage, we see many of the same themes emerge, although less breathlessly than in al-Badeel. We see the same worthiness signifiers, with protestors identified as students and professionals and one image depicting a mother with her child in front of police lines. Depictions of groups standing together in formation yelling slogans and holding signs convey unity, while numbers are clear from full-frame shots of protestors, or again of empty streets. One article cites the “66 thousand” that had joined the Facebook group in support of the strikes. The commitment signifier of resistance to repression is also clear, with articles mentioning high numbers of arrests, and showing flag-waving protestors standing against large numbers of riot police. Topics of other articles include the stoppage of taxis and microbuses due to lack of riders, and mass arrests and protests in various districts. Other articles, though, do indicate the mixed results that the front-page article describes: “At the Mugamma’ [a large downtown state bureaucratic building] workers and state security show up, but citizens do not.” This phrasing indicates that although workers showed up for work, it was not “business as usual.” These patterns persist through the paper’s articles on the strikes later in the issue.

Finally from among the independent/opposition papers we have al-Dostour, headed by Ibrahim Eissa, who was recently pardoned from a six-month prison term for publishing rumors about Hosni Mubarak’s health. The paper ran the headline “Strikes succeed despite interference of government and the Brotherhood, and the parties,” printed over a picture of state-security trucks parked in empty streets. The main photograph depicted a group of protestors (including women and flag-wavers), and two articles appeared alongside it: one discussing police use of tear gas against protestors, and another from a strike organizer claiming that the strikes were “better and bigger than we had expected.” Inside, full-page coverage continued on pages 3-5 with large photos showing empty streets and groups of police. One headline reads: “Cairo: majority of shops close their doors … streets appear completely empty except for the men of the Interior Ministry,” while another announces that security forces were forcing Coptic shop owners to open their stores, even though it was Sunday. As with the other papers, we see the same signifiers appear in high density in the first few pages of the issue. Focused, picture-heavy articles give the issue a high degree of salience; its prominent placement indicates high importance. Coverage centers on WUNC displays, and portrays protestors sympathetically. Among these three “independent” papers sampled, individuals cited for quotation are generally balanced between protest organizers and participants and government or security sources.

A mirror opposite pattern emerges from the three state-run or state-sympathetic newspapers I surveyed: Rose al-Youssef, al-Akhbar, and al-Ahram. While the latter two publications have been running for the better part of a century or more, Rose al-Youssef is the reincarnation of what was once a well-known progressive magazine as a state-sympathetic daily paper. Reports indicate that its funding comes from a wealthy businessman with connections to the regime, and who is friendly to Gamal Mubarak, the president’s son.[ix] Analysis of these papers should provide a clear demonstration of “marginalizing frames” that attack the WUNC characteristics of the protesters.

Rose al-Youssef took the unusual step of running a super-headline (as al-Badeel did) the day of the strikes proclaiming: “Be steady – and don’t be afraid. Go to your work, there are no strikes, and no reason for concern.” The day after the strikes, their headline ran “Defeat of the call to chaos.” While surely this rhetorical flourish stands well on its own, it is clear that by framing the strikes immediately as “chaos” or as a possible cause of fear or concern, they are focusing on “disorder” of the protests, and the implicit need for the state to impose order. The headline continues: “educational system in schools and university and government agencies confirm the failure of the call to strikes,” “the government and the opposition both refuse the strike [called for by] emails and SMS messages,” “3 million Egyptians use the Metro, and 2,800 public transportation vehicles make the rounds through the streets of Cairo, and 34 aircraft took off.” The central picture is of a crowded metro station (an interesting counterpart to the empty metro stations seen in other newspapers), captioned with the slogan of the day: “normal movement in the streets of Egypt.”

Beyond the front page, a short mention is made on page 2 that “government institutions and the private sector” remained as normal. Their strike coverage continued on page 7, where a full page spread declares “Egypt refuses disastrous rumors,” with other articles again describing “stability” and “normality,” or arguing that production had in fact increased. One short article states “strikes afraid of the dust,” making light of the massive spring dust storm that swept thorough Cairo that day. On the last inside page, we find pictures purporting to show Cairo University students skipping class on the day of the strikes and instead playing soccer or shopping. It is not terribly difficult to discern the intended frame here: protestors are not worthy – not only would they have caused chaos, but some members who claimed to be participating were really shirking responsibility – playing games instead of going to class. Their unity and numbers are also called into question by portraying the strikes as a “failure” and emphasizing the absence of protesters, arguing that most in fact did the opposite by going to work or riding the metro. Even the simple jab that protestors were “afraid of the dust storm” challenges their commitment to their cause.

References to police action are not found at all in Rose al-Youssef’s main article, and no images of protestors or police are shown. Strong negative words, such as “incitement” or “rumor” seem to indicate that the protests were merely a hoax designed to harm industry and not a legitimate means of expressing grievances. Very clearly we can see the marginalizing or WUNC-negating frame forming. By spreading the story out through middle and back pages and providing few reinforcing images, the editor is sending a signal that this information is not salient, not very important.

Al-Ahram goes much further in challenging the salience of the issue on its front page: the story of the strikes is not even above the fold, and thus would not be visible on a newsstand. This, in and of itself, is a powerful statement. The top headline of the day instead discusses a diplomatic meeting between President Mubarak and Lebanese Prime Minister Fouad Siniora. The article dealing with the strikes declares: “Work continues as normal in all national institutions and refusal of strikes,” with the subheadline “Just one protest seen in the capital, and a regrettable disturbance in Mahalla al-Kubra. This “disturbance” in Mahalla actually continued for over a week, resulting in State Security barring anyone from entering or exiting and arresting journalists.[x] The short article repeats the claim that production increased, that no factories or companies were affected by strikes; the article states that they were not influenced by the “rumors.” It discusses specific numbers of major operations conducted in hospitals and the functioning of electricity companies. The implication is not terribly subtle that had the strikes succeeded the sick would have gone without treatment and the power would have been shut off. Coverage on page 3 mentions “Just one protest at the Lawyer’s syndicate, and the “regrettable” disturbance in Mahalla al-Kubra.” There is no further coverage of the strikes in the remaining 30 pages.

Here we find a slightly different effect: al-Ahram is clearly attacking the salience of the strikes in a much more strident way than Rose al-Youssef. However, many of the framing elements remain the same: the emphasis that the strikes were a complete failure (not unified or committed, certainly not numerous), and that they were not worthy because they were spreading disruptive rumors and possibly damaging critical state functions such as hospitals or power generators.

The third state-run/sympathetic paper, al-Akhbar’s approach seems to be a mixture of the preceding two. Their headline is large and central, above the fold: “Strikes and attempt at incitement fails.” The subheadline reads: “Work continues (the exact same wording found in al-Ahram) in companies, government institutions and agencies – and university classrooms. Workers achieve increase in production, and consider 6 April a day of work.” The photographs accompanying the article seem to reinforce this headline, depicting factories at work, and the Minister of Education himself sitting in on a class that appears full of students. The article reads: “Egyptians taught a severe lesson to those partisans […] with workers heading to their factories.” Page three continues coverage with “The people say no to strikes in every governorate” and repeats the claim that production increased in factories. One source is quoted saying that “certain powers tried to get workers to damage stability.” Another article on page 4 is headlined “the benefit of Egypt above the masses” and continues on the theme of increased production. The sources for these articles, and indeed in all three government-sympathetic papers, are nearly all government officials. One article quotes unnamed “experts” as stating that the “plans” of those seeking to stir up “commotion” failed.

Again we are presented with a convincing and more forceful attempt to delegitimize the protests; the same pattern seen above repeats, even down to the exact wording in some cases. Yet again, we see that protestors themselves are invisible: not pictured, and not interviewed at all. Al-Akhbar does, however, give much more prominence to their articles on the protests than al-Ahram. All three papers, whether seeking to ignore the issue or addressing it directly, tend to use framings that negate demonstrators’ claims to WUNC. Their framing of the protests as order versus disorder and reliance on government or security officials as sources shows strong similarities to the marginalization tactics described by Rinnawi.

Having addressed each of the papers in the case, there are two other factors that need to be mentioned: structural disparities, and the effects of state coercion. While all three independent papers are just that – independent – and thus reliant on their own financial means and advertising to stay in business, both al-Ahram and al‑Akhbar are state-owned and financed, giving them effectively infinite resources. Rose al-Youssef, although not officially nationalized, is funded by a large donor and is reported to lose money on every issue published.[xi] What are the implications of this for our study? If these papers do not require profitability, they can devote more print space to text and less to advertising, and are able to achieve wider distribution. Indeed, some of the independent newspapers are barely available outside of Cairo while most of the government sympathetic papers are available throughout the country (especially al-Ahram and al-Akhbar). Thus even if their frame is less resonant with readers, by giving it wider distribution it is able to achieve more influence.

Although I do not address the end effects of this framing contest, I argue that the real goal for the government is not necessarily to create a 100% convincing frame. All that is required is to erode confidence in the opposing frame on a large scale. The strong marginalizing frame seen above will reinforce the perceptions of those elites who already support the government, and will chisel away slightly at the influence of opposing frames on the perceptions of those who do not. The government has another tool in its chest as well: the coercive power of its courts and security apparatuses.

Although censorship is ostensibly banned, its influence lives on through the arrest of editors and journalists such as the recent well-publicized case of Ibrahim Eissa, editor in chief of al-Dostour.[xii] The most important aspect of this quasi-official censorship, though, remains the continuing power of the state to influence discourse in the way that it desires. Although lacking absolute power to regulate speech, the judicious use of legal and physical threats provides a hand on the rudder that can be used to “steer” coverage in the direction of its liking.

On the 2009 strikes

One year later, a renewed call for nationwide protests supported by some political parties and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood saw only a very small response and nothing near the scale of the disturbances in Mahalla al-Kubra in 2008. The outcome of the April 6 strikes of 2008 was very much unclear. If a person stayed home was this because they were afraid of police or because they supported the strikes? This ambiguous outcome provided the media greater latitude to impose their version of events. The events of 2009, however, did not lend themselves to the same degree of flexible interpretation.

Coverage in the government-produced or sympathetic dailies followed predictable patterns, according to the Egyptian blog The Arabist. Al-Ahram ignored the strikes, Rose al-Youssef proclaimed “new defeats” for protest supporters, while al-Akhbar emphasized the problems of “chaos” or “production stoppage” that might accompany strikes. Al-Badeel, al-Dostour, and al-Masry al-Youm referred to protests as weak, small and failed, respectively.[xiii] What are the implications of the 2009 strike for our study of framing?

In a very real way, the 2009 strikes illustrate how media outlets are ultimately bound by the facts on the ground, and can neither create a successful protest from whole cloth nor report on movements that don’t exist. Although independent media in Egypt operate in a difficult environment of both intimidation and structural constraints, they should not seek to counter the tactics that I describe by simply publishing mirror opposite framings of the government press. Frame resonance increases with credibility, so these media outlets should concentrate on being seen as a reliable source of information rather than scoring points. The best counter to the pervasive state-centric frame will be a credible, resonant and, most importantly, accurate portrayal of events.

Aaron Reese is a Master’s candidate in Georgetown University’s Arab Studies program, and received his bachelor’s from Rice University. He spent 2007-2008 studying at the American University in Cairo.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub