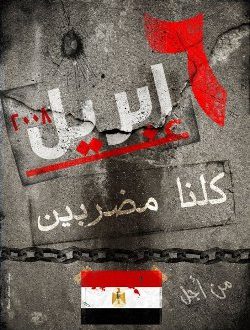

Observers of the Egyptian April 6th Facebook Group and its online mobilization in 2008 lavished attention on the possibilities of so-called “Facebook activism.” Western journalists and activists alike touted the potential of using Facebook to organize, a process imagined as “tapping into the ready-made structure of online social networks to make joining a group as quick as a click of a button.”[i] On the valuable piece of real estate known as the Washington Post’s op-ed page, Nir Boms hailed Facebook as the latest weapon against authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. “Facebook,” he claimed, “is quickly turning into a hotbed of ‘actual’ activism - a cause for alarm for many autocratic regimes in the Middle East....”[ii] Newsweek’s Jack Fairweather called Facebook “an important platform for dissent” in the Middle East.[iii]

Much of this attention was inspired by the perceived success of the April 6th Facebook activists in organizing a general strike in authoritarian Egypt. Barely a year later, however, local and global enthusiasm for the potential of Facebook activism was severely challenged when the group’s one-year follow-up strike ended as a highly publicized failure. Particularly in Egypt, Facebook activism is now dismissed as useless at best, and the failure of the April 6th group to engender a lasting political movement has come to symbolize the futility of even trying. However, a closer look at what really happened on April 6th of each year may offer some hope for the future of electronic activism in Egypt, as well as a more realistic appraisal of its possibilities and limitations. In particular, we need to understand how Facebook and other applications of Web 2.0 might contribute to the kind of broad-based grassroots political coalition that could in fact force the Mubarak regime into a genuine process of democratization.[iv]

Activism and demonstrations in authoritarian Egypt

In Khaled Al Khamissi’s wildly popular Taxi, the author relates a conversation with a cab driver who ridicules the size of a Cairo street demonstration held by the opposition group Kefaya [v]. “In the old days,” said the driver, “we used to go out on the streets with 50,000 people, with 100,000. But now there’s nothing that matters.”[vi] The driver located what he called “the beginning of the end” with the bread riots that rattled the Sadat regime in January 1977. The regime quashed that proto-revolution, “And since then the government has planted in us a fear of hunger….They planted hunger in the belly of every Egyptian, a terror that made everyone look out for himself or say ‘Why should I make it my problem?’” Clearly rattled by the driver, who was able to recall the exact dates of the 1977 demonstrations, Al Khamissi wondered what “the end” actually was.

Perhaps the end was the decades-long interregnum in street protests in Egypt, a pause that seemingly came to a close with the Second Intifada and the demonstration wave that has swept Egypt since 2003. But it is certainly true that opposition forces outside of the labor movement have struggled to put those kinds of numbers on the streets – a feat that might truly threaten the regime of Hosni Mubarak and the emergency law that has governed Egypt throughout his near 28 years of rule. Most demonstrations today consist of more riot police and plainclothes police (the dreaded bultagiyya, or thugs) than actual demonstrators. Al Khamissi’s driver put his finger on precisely the obstacle to collective action that plagues any attempt to spur change from below in Egypt – the question of why anyone should make anything their problem.

This assumption of apathy is perhaps why the regime appeared so threatened by the April 6, 2008 general strike, above and beyond the labor-based tumult that took place in Mahalla, north of Cairo. A Facebook group, which gathered more than 70,000 supporters in a few short weeks, organized a sympathy strike with the Mahalla textile workers that drew national and international attention, and arguably succeeded in shutting down daily activity in parts of Cairo and elsewhere in Egypt. If nothing else, the state took the threat of these activists quite seriously, even political observers in the country dismissed them as an ephemeral phenomenon, or worse, as dilettantes distracting organizers from the hard work of building a real opposition movement.

Since the 2008 strike, the leaders of the April 6th Youth Movement, as it came to be called, have been harassed and imprisoned, and the movement itself is now riven with the kind of factional splits the regime has long exploited to destroy its opposition, its de facto leader accused of seeking money from an American organization believed to have ties to the CIA. And the 2009 follow-up strike, staged on the one-year anniversary of the 2008 action, was widely regarded a colossal failure, another end to another beginning.

Like most political protests in Egypt today, it consisted of a few demonstrators surrounded by riot police, and the Egyptian public apparently ignored the call to stay at home in protest. This 2009 failure has led to an epidemic of cynicism, with activists believing that the halting openings in Egyptian public life that appeared between 2003 and 2006 have now been closed for good.

This article explores the reasons for the failure of the April 6, 2009 follow-up strike, and searches for signs that it may form only the end of the beginning, with future popular movements still bound to arise and shake up Egyptian politics in more grand-scale and lasting ways. It is not that nothing matters, as Al Khamissi’s driver might argue, but rather that organizers have not yet discovered and exploited what matters.

Crushing dissent: The state and the April 6th movement

Sensing that Egypt’s diverse political oppositions had won at least a symbolic victory on April 6, 2008, the regime set about making sure that such a convergence of technology, organizing abilities, and symbolic pressure on the regime would be hard to come by if organizers attempted a similar action again. Ironically, it may have been the movement’s very success in drawing press attention to itself that provoked the state to crack down so hard. As Hossam El-Hamalawy argues, “They scared the regime about what was going to happen that day. The April 6th guys came into the picture – around that time that had 70,000 plus members – and the newspapers dealt with it very sensationally.”[vii] Hamalawy believes that it was this press attention that distracted activists from the actual demands of the Mahalla workers and allowed the state to co-opt substantial portions of the strike leadership, splitting the leadership of the Mahalla workers between those allied with the state, including the local branch of the General Union of Textile Workers (GUTW) and those seeking an independent federation, including the Textile Workers League. Most importantly, some media outlets reported that certain strike leaders had secretly taken a no-strike pledge. It also did not help that the state flooded the factories with security services starting at 3 a.m., hoping to forestall any militant action.[viii]

The regime’s strategy for dealing with a follow-up strike was given a test run on May 4, 2008 when the April 6th movement attempted to stage another general strike on Mubarak’s birthday. The message behind this planned action failed to resonate with the masses, however, and given that it came on the heels of the arrests of well-known members of the movement itself, the strike attempt ended in failure. Then between May 4, 2008, and April 6, 2009, the Mubarak regime employed three distinct strategies to derail the April 6th movement – economic, repressive, and technological.

The repressive end was most familiar and the easiest to execute. The leadership of the group itself was hounded practically into submission, and many bloggers and activists affiliated with the group were arrested.[ix] First there was the forced exit of Esraa Abdel Fattah, one of the founders of the original April 6th Facebook group, from political life. Kidnapped and held for weeks, Abdel Fattah proclaimed when released that she would no longer be participating in politics. Her abrupt about-face from online organizer to quiescent subject set the tone for what the regime hoped to accomplish with Egyptian youth at large. Core leaders of the group, including Ahmed Maher and Mohamed Adel, also saw prison time. At the same time, the regime conducted an even more brutal and wide-ranging campaign against the labor movement in Mahalla, putting 49 workers on trial in the High State Security Court.

Apparently the regime felt so threatened by this movement, and by the online organizers who formed its core, that it took measures to crush it at the roots. The regime succeeded in instilling so much fear in most activists that many have saved text messages on their cell phones that are ready to send off to human rights lawyers, friends, and family when they’re inevitably snatched off the streets. And many more young people have been dissuaded from joining such movements in the first place, preferring instead to pursue the creature comforts of post-Infitah Egypt[AMS3][x]. Why risk getting your skull cracked in a demonstration when you could be relaxing in Ain Sukhna or the Sinai? Especially when experience has shown that would only be in vain.

The Mahalla workers, in solidarity with whom the April 6th general strike was organized, were also brutally repressed. As the blogger Sandmonkey argues,

As for the real heroes of April 6th, the poor underpaid and courageous workers who took a stand that day? Well, they were never interviewed by the media, or the satellite news networks, never were invited to a conference, or were the focus of a news piece. What they were the focus on, was the government's vengeance.[xi]

The scuffle in Mahalla was part of a long-running and intensifying battle between the Egyptian state and the labor sector – with 650 workers’ protests held between 2006 and 2007.[xii] Egyptian labor is organized under the umbrella of the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF), an organization that scholars consider to be co-opted by the state and largely part of the official power structure. Some scholars argue that even under these conditions labor has been able to wring concessions from the government, but overall the labor movement remains repressed and suffers from a lack of autonomy.[xiii]

Some elements of the labor movement are now seeking to construct trade federations outside the structure of ETUF, and the tax collectors recently had success in their campaign. Despite such victories, however, the state has conceded just enough to forestall the kind of national movement that the Mahalla strike seemed to threaten. Just before the planned May 4, 2008 strike, the government announced a 30 percent wage increase.[xiv] Targeted salary increases have also been waved before certain professional sectors (such as doctors) in an effort to defuse potentially serious labor disagreements.[xv]

So the regime capably executed its control strategies on the economic and repressive fronts. But what happened in the realm of technology, where the activists where supposed to have their greatest advantage?

Network theories and the failure of April 6th

What social media technologies help to solve, or at least alleviate, are obstacles to collective action and the dissemination of information.[xvi] Facebook and other forms of social media, including Twitter, blogs, and photo-sharing sites, lower the costs of forming groups, joining groups, and sharing information. They facilitate the rapid transmission of personally relevant information; “Because information in the system is passed along by friends and friends of friends (or at least contacts of contacts), people tend to get information that is also of interest to their friends,” notes Shirky.[xvii] Since social media technologies also reduce the distance between established networks of friends and acquaintances, they can serve as critical components in the building of shared meaning.

What Facebook did for the original strike group was to construct, very easily, a symbolic call to action that allowed a maximum number of people to join with the least amount of effort. The outcome was that the Egyptian state was confronted – almost overnight, since the group grew from nothing to 70,000 members in a matter of weeks – with what it regarded as a serious threat to its legitimacy. Whether Egyptians stayed home because they supported the strike or feared going into the streets remains an open question that is unlikely to be resolved. But the reality is that at least some sectors of the regime, and many international observers, regarded the strike a success and gave a good share of the credit to the April 6th organizers and the Facebook tools that made their efforts possible.

However, the problems that the April 6th movement had in organizing follow-up actions appeared to be unrelated to both the costs of collective action and the challenges of disseminating information in an authoritarian media environment. It appears that the movement’s message simply did not resonate with enough Egyptians to make a difference in the larger scheme of things, and that not enough groundwork had been laid by actual on-the-ground organizers. The call to strike on the anniversary of…a strike ... did not seem to most potential participants in collective action as worthy of the risks involved with either taking to the streets or skipping work and staying home. Such risks are substantial, even if one is predisposed to suffer for a cause.

In terms of ideas, most observers agree that the action was poorly conceptualized. Anniversary actions would probably only be a success if they commemorated an occasion of much larger significance – which is not to underestimate what took place in 2008, but rather to emphasize the fact that the greatest resistance had taken place in Mahalla and that it ultimately all ended with the regime more or less victorious. In other words, it wasn’t exactly clear what was being commemorated on April 6, 2009. So with the Mubarak regime having proven that the potential costs of repression remain very high in Egypt, most young people in the country took the rational approach and decided that they would let other people make a political statement for them. And in classic prisoner’s dilemma form, that statement was never made because the vast majority of people made precisely the same calculation. This outcome is also in keeping with the findings of collective action literature that suggests it is the presence of cogent demands that drives protest movements, rather than new technologies themselves. The youthful, elite organizers of the April 6th movement, social media technology in hand, are simply not capable of singlehandedly manufacturing the conditions that might lead to widespread protest in Egypt.

Another conceptual obstacle to the success of the 2009 follow-up strike was related to a factional split that can partly be traced to rumors about funding the movement - Ahmed Maher himself is alleged to have sought cash from Freedom House, an organization believed to have ties to the US foreign security apparatus. Rumors of CIA involvement in the April 6th movement crippled the activists’ credibility at a critical juncture and turned the group’s Facebook page into a battleground. Group leaders denied they had worked with Freedom House and reaffirmed their commitment to barring foreign involvement in the movement, but the damage appeared to have already been done.[xviii] One activist told me that while opposition forces are happy to accept technical assistance from foreign promoters of democracy, the acceptance of cash from organizations with known agendas can be deadly for the public credibility of organizers.[xix]

To truly understand the failure of the April 6, 2009 message, however, we must first understand what it was about the message of the previous year that had resonated with so many people. At the time, Egypt was undergoing price increases for basic staples just as the global economy was beginning to take a turn for the worse. Even those individuals who didn’t know anyone in Mahalla or particularly care about the fate of striking textile workers had an access point to the movement’s message about economic justice. The increase in the price of bread, in particular, called to mind the reason for Egypt’s last large-scale street action in 1977. And most importantly, the general strike call was yoked to a concrete, on-the-ground action – the strike of Mahalla textile workers and their demands for better wages and working conditions. Without the very real foment in the streets of that city and its emotive effect on Egyptian observers, it is unlikely that anyone in Cairo or Alexandria would have cared enough to join this kind of a Facebook group to begin with.

It was the absence of such a clear message that led to confusion about the purpose of the follow-up strike in 2009. Individuals were asked to stay home and not buy anything – but if they had to leave the house, to wear black. All of this was allegedly to protest the injustices perpetrated during and after the April 6, 2008 strike, making the whole movement somewhat self-referential. Given that the message of the April 6th movement had not reached important sections of the Egyptian population to begin with, basing the follow-up strike on the repression following the 2008 strike was probably not a wise tactic. Still, there were concrete demands. According to the movement, the April 6, 2009 strike had four: the institution of a national minimum wage, the indexing of prices to inflation, the election of a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution, and the suspension of gas exports to Israel.[xx] The third demand in particular was unrealistic at best, and probably only served to underline the regime's fears about the movement's true goals. The demand for a national minimum wage was almost certainly undermined by the regime's success in buying off sectors of the labor movement with wage increases. While this was less the fault of the movement than a success for the regime, it still points to the movement’s failure to craft an effective message. Finally, the demand regarding Egypt’s relations with Israel probably only served to muddy the waters.

Yet in addition to the fact that the organizers failed to develop a credible and mobilizing message to feed into their social networking tools, certain limitations to the potential of Facebook organizing itself presented challenges to the planned 2009 strike.

To begin with, Facebook groups seem to engender extraordinarily low levels of commitment on the part of their members. While the technical capabilities of Facebook – such as the public nature of “status updates” and the ability of users to change their profile picture to adopt a popular symbol– lend themselves to the production and dissemination of ideas, they do not necessarily facilitate the active and sustained mobilization of individuals. Ethan Zuckerman points to the problem of “serial activists”, who jump from cause to cause and join group after group – Gaza, April 6th, freeing Ayman Nour – without ever making a real investment of time or energy in any of them.[xxi] This potential for lack of commitment should have been understood when the movement’s initial follow-up action, the May 4th strike, turned out to be such a resounding failure.

So while the April 6th Facebook page still has 70,000 members, very few of them remain actively involved, whether on the group’s message board or in real life. According to one of April 6th’s senior members, the movement maintains only about 2,000 full-time members on the ground.[xxii] The April 6th movement eventually grasped this commitment problem and created a web presence [xxiii] to complement its Facebook profile, but even these technologies in tandem can't mobilize people without concomitant movement on the ground.

And in addition to engendering low levels of commitment, features of Facebook’s interface can actually undermine its utility under certain circumstances and be counterproductive to effective online organizing. Particularly at the height of a crisis, for example, the “wall” of a group and the main Facebook status update page of an individual can be inundated with messages. “In that flood of data, it’s possible to lose key messages,” contends Zuckerman.[xxiv]

A focus on Facebook also appears to have missed the apparent shift of online dissent from blogs to Twitter. As Hossam El-Hamalawy puts it, “the migration is not happening to Facebook, it’s happening to the microblogs.”[xxv] He adds, “Facebook is one of the outlets I have, but the heavyweights are not using Facebook.” The heavyweight bloggers El-Hamalawy refers to were skeptical of the April 6th movement and its potential, even before the first strike. As blogger Demagh MAK puts it, “The thing is that it’s just easier to use Twitter than a blog. You are in the middle of a demonstration and someone is killed or arrested -- you can’t leave the demonstration and write a blog. One is killed two arrested; you can just send it by Twitter and everybody now knows.”[xxvi] And in fact, it was Twitter that served as the most important clearinghouse for information regarding the events of April 6, 2009.

The decline of the April 6th movement has been caused by more than poorly framed messages, recourse to ration, and the inherent weaknesses of its main technological tool, however. The Mubarak regime has grown much savvier over the past year with respect to interfering with the communications efforts of activists, making it significantly more difficult for individuals to conduct activism via the tools of the internet and mobile phones. For starters, a sophisticated registration-and-tracing system is now in place for mobile phones, allowing the government to track users, interfere with their signals, and shut down large-scale attempts to text message. The Egyptian government successfully blocked the routes of activists’ text messages during the 2009 strike. As one of the primary organizers and leaders of the April 6th movement, says of the 2008 strike,

In 2008, we used SMS, we used mobile technology to contact all the people. We sent SMS asking people to call everyone and tell them there is a strike, and for people to use SMS to send us information. All of my friends, members of Kefaya, the parties, we sent SMS to numbers we didn’t know, we sent 2 million bulk mails, and about 50,000 SMS messages.[xxvii]

The blocking of the text-messaging service vastly complicated the efforts of the organizers, who were already cash-strapped. For another part of the problem is simple financial logistics – Egyptian telecommunication companies don’t offer unlimited texting services like those available in other countries. In the United States, for instance, for only a few dollars a month one can purchase a plan that allows one to send unlimited text messages, thus facilitating mass messaging, the coordination of far flung and wide ranging action, and the ability to adjust plans on the go. According to one April 6th leader, the movement tried to get around this obstacle by purchasing text-messages in bulk from India at a rate of $.01 per message, but the regime successfully blocked these messages as well. This meant that the only coordinating mechanism on the ground the day of the 2009 strike was the micro-blogging service Twitter, although this too had shut down its component that allows users to send text messages, meaning Twitter messages had to be sent via the Mobile Web rather than SMS. That change significantly raised the costs of using Twitter on the go. Those activists who can afford the pricy costs of the mobile web, either through USB internet connections or their cell phones, were still able to communicate and send many-to-many communications through Twitter, but they were limited to the wealthy few. And stripping the April 6th activists of their messaging capabilities left them with essentially no means of executing or altering their plans after it became clear that the state was ready for them.

The regime has also instituted changes in the structure of internet cafes, vital sites of access to the internet for the average citizen that had been critical to the building of online public spheres in Egypt and in particular the creation and initial success of the April 6th movement. For years individuals had been able to enter cafés and get online with minimal interference from either café owners or the state. However, as of August 2008, café owners were required to collect vital information about the individuals using their computers.[xxviii] There can be little doubt about the intent of these regulations, and while their effect might be limited in practice, on a symbolic level the attempt to regulate access so closely could only have a chilling effect on the kind of writing, dissent, and activism individuals are willing to engage in. While sympathetic café owners still provide access to activists without collecting this information, it nevertheless forms an additional hurdle to spreading information by creating a general environment characterized by the threat of surveillance, coercion, and arrest. The reduction in the number of locations where unfettered internet access is available for a low cost can only reduce the network transmission capabilities of the technology and interfere with the ability of organizers to communicate and implement their plans.

Potentially a workaround to the clampdown on internet cafés, Egyptian telecommunication companies now offer mobile internet access via USB modems that are convenient for use on personal laptop computers.[xxix] This is in many ways a unique and useful service, enabling individuals to bypass the unwieldy process of having an internet connection set up in their homes, which for fast and reliable connections can be an expensive and time-consuming endeavor. Activists tell me that this USB connection is quite good, works most anywhere, and is very fast. However, the process of obtaining these devices also falls under state surveillance, as applicants are required to submit identity papers, addresses, and phone numbers, making it possible for users to be tracked by the service providers and hence the state authorities. Like all attempts at interfering with internet access, on-the-ground realities offer any number of workarounds, as sympathetic merchants are sometimes willing to sell USB modems to individuals submitting fake or falsified information. However, as with many attempts to step between the web and potential users, this measure is not necessarily about perfecting enforcement or stopping the truly dedicated and savvy user from accessing the internet. Rather, it’s about placing roadblocks between the internet and users in the same way that slowing down the load time of a web page will deter many individuals from bothering with that page at all.

Finally, activists also have to contend with the reality of de facto non-generative technologies. Zittrain defines generativity as “a system’s capacity to produce unanticipated change through unfiltered contributions from broad and varied audiences.”[xxx] In other words, while many internet technologies were designed to be “open boxes” amenable to alteration by their owners, non-generative technologies are more like closed boxes, tied to their manufacturers and vulnerable to remote alteration, tracking, and destruction. Examples of non-generative devices include the ipod and TiVo; an examples of a generative devices would be the eminently adaptable and reprogrammable PC. Zittrain argues that you can think of this as the difference between “contributors or participants rather than mere consumers.” In the US, non-generativity is related to issues of profits and corporate interest, but in Egypt it is more closely related to surveillance and control, and is the model instituted by the regime and Egyptian telecommunication companies for accessing the Internet and using mobile devices.

Organizers from the April 6th movement have described what such non-generativity means for them in practice – while it’s easy to change your mobile phone’s “simcard” and hence your number, the phones themselves contain a chip that can’t be removed or altered, making it possible for your initial service provider to track that phone indefinitely. The capabilities of the mobile phone can thus go in two directions, both enabling users to communicate with them and regimes to silence them – as illustrated by the events of June 2009 in Iran. When the Green Revolution took shape, the government shut down the text-messaging network[xxxi]; Iranians were still able to access the Internet, either directly or through proxy servers, and therefore update various forms of social media communication. Yet the shutdown occurred at a critical moment during the Iranian events, preventing individuals and organizers from using their mobile phones as coordinating and frame-building devices and thus essentially crippling the capacity of mobile phones to serve as an accelerant when most needed.

The cumulative effect of such deterrents can frustrate technology users to the point of simply accepting that there are things they can’t or shouldn’t be doing. Removing these individual nodes from a large network can slow down the information transmission capacity of social media and compromise their utility, in keeping with Metcalfe’s law about the value of communications networks growing as the number of their users rises.[xxxii] It doesn’t seem that the Egyptian regime intends to shut down networks altogether (though that of course remains an ever present possibility, particularly during short-term crises). Rather, its aim seems to be creating uncertainty and hardship for activists engaging with technological tools at the same time that are persecuted in much more straightforward and old-fashioned ways.[xxxiii] The number of activists willing to put up both with state harassment and technical interference is surely not as high as the number of activists willing to engage in this activity absent such efforts.

Conclusion

It would be unfortunate if the failure of the April 6th Youth Movement in this one particular instance led to the end of youth activism in Egypt generally, or even the departure of the newly-mobilized urban youth elite from the field of activism. Egyptian youth constitute a substantial majority of the population (58 percent of Egyptians are under 25) and will have to play a critical role in any serious process of political change that may take place in the coming years.[xxxiv] Yet the state these activists are tangling with is a battle-tested authoritarian regime with decades of experience dividing and conquering its opposition. It will take a much savvier opposition, with much clearer goals and a much stronger presence on the ground, to seriously threaten the state. And even with the global financial downturn, there are still enough Egyptians profiting from the economic order that the “end” of the Mubarak regime – if it comes – is likely to be quite unexpected and unplanned, as in the popular response to the Iranian presidential election earlier this year.

As El-Ghobashy argues, there has in fact been a certain democratization of Egyptian public life over the past 25 years – she cites the growth of human rights organizations, the increasing strength of the judiciary, and the revival of professional associations[xxxv]. El-Ghobashy contends that this process has been enabled and accelerated by what she calls the “internationalization” of Egyptian politics. I would add the development of independent media outlets like Al-Masry Al-Youm and Al-Sharouk and the recent struggles of the labor movement to the list of democratic victories that are painstakingly being carved out in Egypt today. Despite the setbacks faced by the various opposition forces, a trend toward democratization has been clear, even as the government has walked back freedoms in other, more high-profile areas.

Yet if a viable opposition is to take shape with the assistance of electronic media like Twitter and Facebook, that opposition will have to pay much more careful attention to the kinds of small-scale struggles over freedom taking place every day in the courts, the press, the labor sector, and the professional associations. Where was the April 6th movement, for instance, on the long-running strike in the Tanta Flax and Oils Company?[xxxvi] Electronic activists will have to pick up the banner of the struggle for an independent labor federation and to pay closer attention to the kinds of battles that can and cannot be won in the courts. It will also have to draw the right conclusions from what worked on April 6, 2008 and what didn’t on April 6, 2009. The 2008 strike probably wasn’t so much a large-scale mobilization as a test run for the kind of information dissemination that the international media has written so extensively about in Iran this year. As El-Hamalawy notes, “It was a day where information technology played a crucial role, the updates coming out of Mahalla, people were exchanging info on Facebook about the strike, they were mobilizing, how can we help, this and that.”[xxxvii]

And future actions should probably be tied either to on-the-ground labor activism or to those areas in which activists and professionals have had the most success contesting the regime’s hegemony: human rights and issues of constitutional and economic justice. These issues are the subject of widespread political agreement among Egypt’s divergent opposition forces,[xxxviii] and if they can successfully pool their resources, social media are likely to play a critical role in building political consensus, coordinating and executing concrete actions, and in putting together international human rights coalitions that can put pressure on the regime. The most promising route might be for the April 6th movement, with its ties to international media organizations and NGOs, to somehow link up with the labor movement in advance of the 2011 presidential elections – even if not all sectors of the opposition agree with the labor movement’s economic principles. As other revolutions have demonstrated, unity around issues of democracy must precede struggles over the post-revolutionary landscape. However, it is up to individual activists to turn the possibilities of social media into reality, and even the most tech-and-politically savvy individuals will continue to face determined resistance from a regime that has so far confounded any and all attempts to challenge its hegemony.

David M. Faris is finishing a PhD in Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania. He conducted extensive fieldwork in Egypt between 2007 and 2009 on the relationship between new media technologies and politics.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub