Since 2011, the Kuwaiti telecom company Zain Group, one of the largest in the Middle East, has produced a series of popular ads broadcast annually during Ramadan. The ads are songs, usually featuring celebrities singing and dancing with children. Since 2015, the ads have become noticeably more political. In 2016, the ad was shot in a refugee camp and featured Arab celebrities singing about suffering and hope. In 2017, the ad carried an anti-terrorism message, and in 2018 it portrayed the plight of Muslims and referenced Palestine, Myanmar, and the refugee crisis. As the ads have become more political, children have been given bigger roles in speaking about politics. While the earlier ads featured adults but seemed to target children as an audience, the latter ones have featured children as protagonists, and are targeted at an adult audience. The period from 2011 to 2018 saw dramatic shifts in the Arab public sphere from an unprecedented burst in freedom of expression during the 2011 uprisings to a renewed overwhelming wave of oppression and censorship.

In 2018, speaking out in most Arab countries remains a dangerous endeavor. In this essay, I will situate the most recent Zain Ramadan ad within this context. Against the backdrop of political oppression, I focus on the mediated child figure because I suggest that when adults are not permitted to speak and have nothing left to say, the child is reconfigured to speak on their behalf. But what can the child figure say?

This brief essay focuses on Zain’s viral 2018 ad, with more than 17 million views on YouTube. The three-minute song features a boy, who appears to be about six years of age, singing to and addressing world leaders. As it went viral, and got circulated on WhatsApp and other social media, it created intense controversy (Sleiman 2018). Arabic speakers were divided. On social media, many celebrated it as a touching message that spoke truth to power. Its detractors were of two camps. Some criticized it for being too political while others complained that its depiction of a child pleading to world leaders is politically demeaning and cringe-worthy. Below, I argue that it is important to analyze what political work the figure of the child is made to embody in popular media texts such as this video. Because children are typically configured as malleable entities in the making, their depiction in media often reflects changing socio-political meanings (Castañeda 2002).

Accordingly, I suggest the ad reflects the current political moment in the Arab world whether in its genre of ‘political ad’ or in its circulation, reception, and content. In the Arab world today, free political debate is under immense pressure and there is a dearth in narratives and representations of public resistance against overwhelming internal oppression, external meddling in the Arab region, and inter-Arab fighting. The fact that an ad by a telecom company went viral and generated a political debate reflects a need to address the collective pains people feel in relation to a divided and humiliated region. This background makes tackling the region’s urgent problems marketable. But of course for something to sell in such an environment, it has to tread the political terrain carefully. And so, what better figure than a child is there to appear to speak about politics without saying anything coherent? It is for this reason, I suggest, the child figure has featured prominently in the purportedly “political” ads of a telecom company reaching out to a pan-Arab market.

The ad has a strange plot and lyrics. It begins with a middle class (judging from his attire) boy walking in a hallway that turns out to be US President Donald Trump’s office. “Mr. President, Ramadan kareem. You are invited to have iftar with me, if you find my home in the debris.” As the child continues his song, we see an actor playing the role of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The song lyrics shift to talking about the refugee crisis as the child sings “and the death boats reach the land of dreams with no children on the cover of magazines”— an indirect criticism of European hostility toward refugees. The video shows people rushing out of boats onto the shore as an actress playing the role of German Chancellor Angela Merkel welcomes them and hugs the children.

The clip next shows the boy lying on a bed in a bedroom singing, “Mr President, I cannot sleep,” as he describes his fear of bombs and war. While he tries to sleep in his bed, the North Korean leader Kim Jong-un comes in—looking touched by the ordeal as he sheds a tear. The boy’s bedroom suddenly becomes destroyed as if his house was just bombed as he sings, “every time I close my eyes I hear an explosion. My bed gets lit up with smoke and fire.” In an apparent reference to the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, we then see fatigued people walking across a forest and crossing a river. The lyrics are: “Mr. President, we are the escapees, the shunned, accused of faith and devotion, sentenced to extermination. Our voices have been silenced for making a faith declaration.”

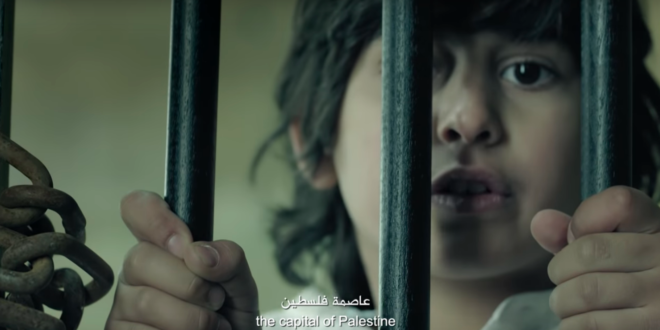

The boy is then back in the office of Trump and has a defiant message about Palestine. He addresses Trump “Mr. President, our iftar will be in Jerusalem, the capital of Palestine.” The boy protagonist then visits a prison cell occupied by a blonde teenage girl wearing the Palestinian Kaffiyyah, a reference to Ahed Tamimi—the iconic teenage activist who got detained in Israel for slapping a soldier in the occupied territories. The boy breaks the lock off the prison cell and both kids run out happily. The last scene shows the protagonist boy and the girl Ahed playing, holding hands as they turn their backs to the camera. They are shown also holding hands with men wearing traditional Gulf clothes representing the different national attire of Gulf Cooperation Council member states. All of them are walking towards the highly recognizable Jerusalem skyline. The issue of Jerusalem, of course, dominated news bulletins for several months in the Spring of 2018, because the US symbolically moved its embassy from Tel Aviv to the disputed city.

The virality of the ad, its widespread interpretation as politically significant, and the controversy it generated, are a symptom of a repressed and troubled public sphere. Several public figures took to Twitter to share the ad and applaud its message. Jordan’s Queen Rania shared the ad in a tweet, which stated “We do well to listen to children’s voices.” A former Omani official tweeted that the ad’s words will “shake the ground underneath Zionists and their supporters,” while a popular Kuwaiti commentator uploaded a video hailing the ad as “a refined message” and dismissing its critics as unable to handle the words ‘Jerusalem is the capital of Palestine.’ Many YouTube videos were uploaded of Americans and Europeans being shown the video by Arab friends and reacting emotionally. However, pro-Saudi voices used the Twitter hashtag ‘Zain ad’ to attack Kuwait—accusing the ad of harboring a pro-Iranian and pro-Muslim Brotherhood message and claiming the content is inappropriate for a telecom ad. The ad was actually banned by the Saudi MBC broadcasting group (Al-Bahawid, 2018) — a sign that no matter how watered-down political representations are, they are deemed too controversial by Saudi media, particularly in relation to the Palestinian struggle. This hostile reaction comes despite the ad’s ambiguous message, for instance when showing the Gulf figures approaching Jerusalem it is unclear whether their path to the holy city is for the purpose of confrontation or the normalization of ties. Other Arab commentators decried the weak message of the ad. Counter YouTube videos were widely shared on social media using the tune of the ad with alternative lyrics about supporting Palestinian resistance, expressing pride in Islam, or hostility towards Western leaders.

Regardless of the controversy about its political message, the ad, in fact, only signals geopolitics but treats it in a de-politicized way with no clear perpetrators. Significantly, only Western/global leaders are portrayed as prone to getting shamed into pity by a crying and pleading Arab child. Rather than politically courageous, Zain’s ad in fact infantilizes the Arab body politic, decontextualizes pressing problems, and, more troublingly, panders to a narrative of helpless victimhood. It reduces the Arab body-politic to a child pleading to Western and global leaders to take the Arab and Muslim plight into consideration. While European and American leaders are recognizable in the ad, we see no Arab leaders. While it shows the scale of suffering in the region and by Muslims globally, it does not hint at any responsibility or context. The suffering of Syrians as refugees and Palestinians as an occupied people is rendered equivalent, as is the suffering of the Rohingya. The only reason given for the suffering is that the victims are Muslim, a convenient self-Orientalising interpretation (Sleiman, 2018) that absolves not only Arab leaders, but also elite audiences, from any sense of accountability or even a responsibility to interpret the reasons for suffering in the region. Is any Arab leader responsible for the plight of refugees? Are Arab leaders complicit in the Israeli occupation? These questions are deemed irrelevant. In addition, the depiction of Ahed Al-Tamimi erases her political agency and absolves the Israeli occupation by failing to depict who arrested the teenager and why. She is portrayed as just a helpless victim rather than a part of a popular movement against occupation.

The ambiguity of the message and representation of helplessness makes the child figure an appropriate political speaker for a weakened political message catered to a marketplace of consumers. Culturally read as innocent and as a symbol of humanity at large, the child figure conceals regressive politics through infantilizing the Arab body-politic and portraying it as a pleading and tragic entity. The child’s tears may be moving but they do not move publics to do anything—only perhaps to become customers of the telecom company. While that is the purpose of the ad, its reading as political indicates an impossible desire to celebrate a moral stance that reflects the region’s pain without deepening the fractures in Arab societies and upsetting any Arab leadership. Within this context, the Arab child is figured as the political speaker when adults are pushed to choose to say nothing at all.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub