Issue 27, winter/spring 2019

https://doi.org/10.70090/IVM27PIR

The impacts of new media have long fascinated scholars of contemporary Muslim societies. Beginning from the premise that new media configurations portend the “fragmentation” of religious authority (Eickelman and Anderson 1999; Anderson 2003), such works often display a curious mix of euphoria and anxiety about the “democratizing” potential of new media; these works also offer opportunities for circulating “radical” ideologies. Few studies, however, offer extended engagement with one particular individual, and when they do, they often gravitate toward the most extreme examples. The prevalence of satellite television has furthermore encouraged scholarly focus on vanguard trends like Salafism (Field and Hamam 2009) or the rise of lay religious authorities (Moll 2010), while those scholars who fuse more “traditional” forms of Islamic discourse with new media technologies (sometimes toiling quietly under nation-state sanction) are generally ignored. As a result, the continuities that hold discursive traditions like Islam together are elided, and the supposed “rupture” that media technologies inflict on it becomes over-amplified.

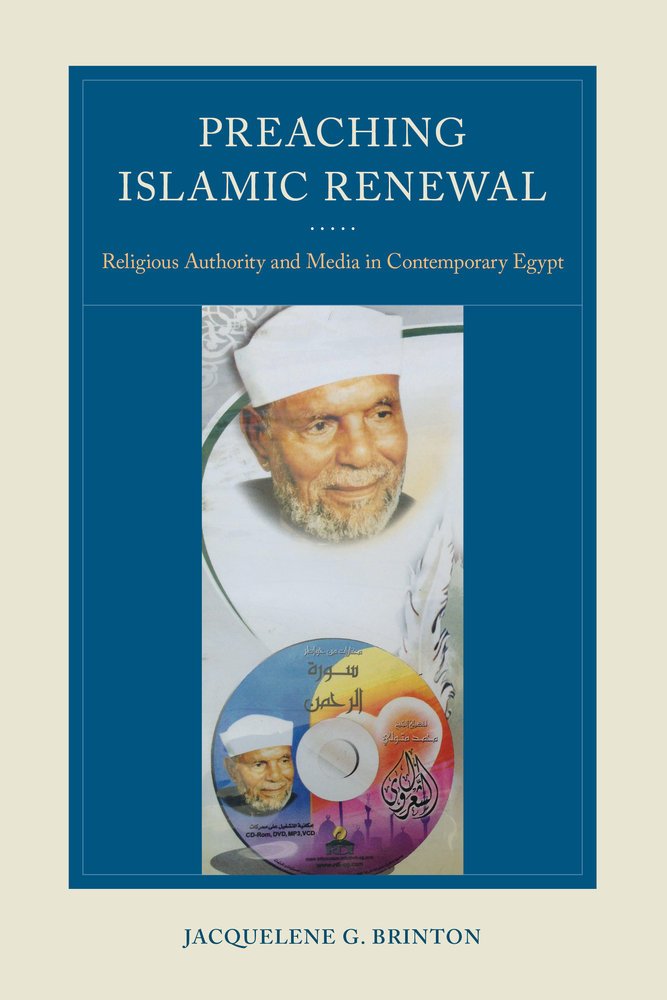

Jacqueline G. Brinton’s Preaching Islamic Renewal is poised to rebut such persistent narratives, offering a comprehensive study of the life and legacy of the Egyptian ‘alim (scholar) Muhammad Mitwalli Sha‘rawi (1911-1998). Sha‘rawi is an interesting case study, Brinton maintains, specifically because of the way he defies such binaries: an Al-Azhar-trained sheikh who became known as a “scholar of the people” (‘alim al-sha‘b) thanks to his television show Nur ‘ala Nur (Light upon light), and broadcasts of his Friday khutbas that reached some 30 million people each week. Building on her analysis of these programs and Sha‘rawi’s written work, along with extensive fieldwork among his followers and acquaintances, Brinton finds that innovative use of media was indeed central to the construction of Sha‘rawi as an authority figure. “Media, specifically television, influenced his discourse in production and reception, but, just as important, it influenced how he, as a man of authority, entered the lives of his viewers. Television transmission, with all of its political, societal, and material aspects, created the phenomenon of Sha‘rawi” (14). At the same time, Sha‘rawi’s influence was not just a matter of this wide circulation, but it was also rooted in more “traditional” sources: his Azhari credentials, his knowledge of classical Arabic, his apparent charisma, and above all, his deep engagement with the Qur’an as a source for personal ethical instruction. Thus, Brinton argues, Sha‘rawi’s impact can best be explained “by focusing less on discovering the gains and losses of particular groups and more on overall media effects.” (182)

Like other anthropologists who employ the biographical form, Brinton narrates Sha‘rawi’s life and work in a two-fold manner, telling a more general story about the evolution of religious authority in Egypt while also highlighting Sha‘rawi’s distinctiveness. In this regard, the recurring discourse of tajdid or “renewal” of the Islamic tradition (the subject of Chapter Three) offers a particularly interesting case. While the nineteenth century reformer Muhammad ‘Abduh saw rational interpretation (ijtihad) as a right and responsibility of all Muslims, and Islamists like Sayyid Qutb blamed the ‘ulama’ for “stagnation” in Islamic tradition, Sha‘rawi reasserted the role of the ‘ulama’ in leading the tajdid process. Similarly, while Islamists objectified Islam as a complete code or system (manhaj) for social life, Sha‘rawi grounded his ethical model in a personal relationship between the individual believer and God. Sha‘rawi combined this “personalization of the concept of virtue” (63) with a number of strategies to make his sermons more relatable. These included the mixing of classical and dialectical (‘amiyya) registers of Arabic, a gentle manner, and the reframing of the traditional genre of Qur’anic exegesis (tafsir) as his personal “thoughts” (khawatir) on the Qur’an’s relevance to everyday life.

Subsequent chapters are also arranged thematically, focusing on different aspects of Sha‘rawi’s discursive authority. Brinton carefully examines Sha‘rawi’s subtle reassertions of traditional knowledge hierarchies (Chapter Five); evocations of Sufi themes and displays of piety (Chapter Six); and the various linguistic strategies the scholar employs—the “metapragmatics” as they are referred to here and in other anthropological literature—to limit interpretation of contested terms (Chapter Seven). The model of religious authority that emerges, Brinton argues, is a relational one: followers not only cede authority to public figures by choosing them over others in a diffused media sphere, they actually help construct the discursive space in which authoritative claims are made through their own engagement. And yet Sha‘rawi’s strength, Brinton suggests, was his ability to recognize this relationality enough to bend it to his own purposes. While urging his audiences to “recognize and authorize those capable of applying God’s cure to solve the problems of humanity,” he simultaneously “sought to train the public to recognize that the knowledge derived by the Sunni scholars of his orientation was the true representation of God’s message” (111).

Media scholars will undoubtedly be most drawn to Brinton’s final chapter, “Television and the Extension of Authority,” in which the author looks to foreground the affective potential of the televisual medium itself. Engaging Bourdieu’s work on television and a handful of affect theorists—Massumi (2004) is surprisingly absent—Brinton attempts to show how “Sha‘rawi’s legacy as a televised religious guide was based primarily on elements of appeal and expectation, or seeing and feeling, that were enhanced through television as a visual medium” (184). This visual appeal is demonstrated by the widespread practice of people putting up Sha‘rawi’s image in their personal spaces after his death, an act in seeming defiance of his verbal injunctions that his image or grave not become objects of worship. For Brinton, this case seems to illustrate how affective transmission can both enhance authoritative charisma, but also overflow the discursive boundaries of Sha‘rawi’s own authoritative position. However, the chapter’s impact is hampered both theoretically and empirically. Brinton does not provide enough ethnographic material from Sha‘rawi’s television viewers, nor those who engage his photographic likeness devotionally, to offer insight into how affective transmission actually occurs. Additionally, while Brinton acknowledges the multi-sensorial aspects of television (188), her overall model and the one ethnographic example she offers seem to reduce it to a purely visual medium.

In the midst of such limitations, a more fundamental issue seems to remain unaddressed: how ideologies of televisual immediacy encourage, in particular, the traditional grounding of Sha‘rawi’s authority that the rest of the book does well in highlighting. This might require rethinking Bourdieu’s concept of television’s “reality effect” (185): people take televisual presence to be “real” because what they see on the screen appear to be things “as they are.” While Brinton is rightly critical of this, such ideologies are still quite potent, particularly in Yusuf al-Qaradawi’s justification of photographic and televisual depictions of the human image on the grounds that, unlike painting, these genres are not acts of “creation” because they merely “represent what is actually present” (193). Thus, one still wonders about the potential link between this televisual “reality” and constructions of authority more generally. One theme that recurs throughout the book is the way Sha‘rawi’s personal characteristics undergirded his authority: his charisma and pious comportment modelled the type of relationship he wanted his viewers to have with God. At the same time, Brinton shows clearly how firmly-rooted Sha‘rawi was in “traditional” models of authority and knowledge production, one predicated on direct teacher-discipline relations, even as he was trying to extend these relations to a mass audience. Given these factors, it seems plausible that Sha‘rawi’s authority relied not just on the wider circulation that television allows, but also on its fundamental ideology of presence that anchors any sort of affective relation—a sort of extension of Walter Ong’s “secondary orality” (Ong 1982; see also Messick 1996). Moreover, how do these factors relate to Sha‘rawi’s individual-focused framing of Islamic ethics? Does this ethical model somehow resonate best within the indeterminacies of television’s “secondary reception” (181)? And what does all of this mean for the relational model of authority Brinton highlights earlier? Although thorough answers to all these questions may not be possible in the span of a single chapter, connecting such media ideologies to the text’s other valuable arguments about religious authority might have given it greater coherence overall.

Whatever its limitations, Preaching Islamic Renewal remains a valuable text for scholars of contemporary Islam, thanks to its multi-layered engagement with issues of media and contemporary religious authority. Media scholars, too, should find the text provocative, raising important questions for future research.

Preaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary Egypt

Jacqueline G. Brinton

(University of California Press, 2016)

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub