Issue 38, Summer/Fall 2024

http://doi.org/10.70090/AMS.38.DT1

Abstract

This research seeks to identify influential online actors on X and study the thematic narratives in the digital public sphere, with a specific focus on communications pertaining to Palestinian protests. In challenging the mainstream narratives propagated by traditional media outlets in some Western countries, the global proliferation of digital media has facilitated the empowerment of underrepresented groups during the Gaza war in 2023. Against this backdrop, this research paper examines the role of X (formerly Twitter) in shaping the digital public sphere during the transnational pro-Palestine protests. The significance of the study lies in understanding the power of digital media in echoing the voices of influential online actors who diffuse information, document events, organize protests, and foster global solidarity for Palestine. Using a mixed-methodological approach, this research quantitatively examines 11,351 X posts that contain keywords relating to pro-Palestine protests, which were extracted using NodeXL Pro. Additionally, it qualitatively analyzes the content shared by the top 30 influencers. The results indicate that some traditional media organizations extend their roles as influencers into the digital environment. However, several activists and concerned citizens from diverse nationalities also actively shape narratives and positively portray the pro-Palestine protests.

Introduction

Israel’s latest large-scale military operation in Gaza was launched in response to an attack by Hamas on October 7th, 2023. As of publication, the ongoing violent incursion into Gaza by Israel has killed more than 56,500 people (United Nations 2025). This latest war in Gaza prompted global protests, demands for an immediate ceasefire, and accountability for Israeli human rights violations. On April 17, 2024, students at Columbia University set up a Gaza solidarity encampment on their campus, which inspired similar on-campus and off-campus protests throughout the world (Reuters 2024; Delandro 2024).

The proliferation of transnational pro-Palestine protests was a signal of global solidarity with Palestinians who are struggling to survive. However, ostensibly democratic governments in the West actively suppressed and silenced many protests. The Time Magazine article, “New Report Details How Pro-Palestine Protests are Suppressed in Democratic Countries,” quoted Tara Petrović as saying, “We’ve seen expressions of solidarity and we’ve seen repression of these expressions of solidarity at pretty much every corner of the globe” (Serhan 2024). Petrović was the author of a report published by CIVICUS Monitor, which determined that many protests were prohibited in multiple Western countries, which included France, Latvia, and Singapore (CIVICUS 2024). In addition, activists, writers, and concerned citizens were harassed after publicly speaking against Israel’s violations of Palestinian human rights. For instance, Australia’s State Library of Victoria terminated the contracts of four writers, which included Omar Sakr, Jinghua Qian, and Alison Evans. These authors publicly stood against Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza (Burke 2024). The CIVICUS report (2024) added that several students in the US and UK were arrested and interrogated for setting up encampments on campuses and expressing solidarity with Palestinians on social media.

Despite the active attempts to suppress transnational pro-Palestine protests, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED), a non-profit organization, recorded more than 30,000 pro-Palestine protests in 133 countries. Notably, only one percent of these protests resulted in reports of violence, which reveals the peacefulness of these events (Murillo & De Paris 2024). Simultaneously, online users exploited several social media platforms to mobilize demonstrations and influence public opinion regarding pro-Palestine protests. This research focuses on X as a digital platform that provides ordinary people, activists, and alternative media the capacity to challenge mainstream narratives propagated by traditional media and governmental institutions.

Literature Review & Theoretical Framework

The current research study seeks to understand the dynamics by which influential actors shape discourse during protest movements on X through the lens of networked publics and the digital public sphere. In this context, X serves as a key site of political engagement, enabling decentralized actors to influence online public narratives. Accordingly, this section aims to lay a theoretical foundation to understand the problem under investigation by critically reviewing existing scholarship and theoretical discussion of the digital public sphere and the role of X in political engagement.

New Public Sphere: Social Media

According to German Philosopher Jürgen Habermas, the public sphere is a social realm “in which something approaching public opinion can be formed. Access is guaranteed to all citizens. A portion of the public sphere comes into being in every conversation in which private individuals assemble to form a public body” (Habermas 1974, p.49). This social realm, where people met in coffee houses in the eighteenth century to exchange opinions and discuss public affairs, has traditionally been limited to the bourgeoisie. However, technological development has led to the inclusion of a wider section of the population as the communication channels, such as print media, have developed. Habermas criticizes some forms of mass media, such as radio and television, as inept at dismantling the public sphere because they promote a unidirectional flow of information. This type of one-way communication does not allow audiences to interact or respond to the content, which highlights the power of the political economy in shaping media dynamics (Habermas 1991).

The arrival of the Internet and social media platforms has reconstituted the traditional public sphere with a new digitized public sphere. Several scholars (Peter Dahlgren 2005; Manel Castells 2008; Dilli B. Edingo 2021) conceptualize social media as a new public sphere, which includes the basic defining attributes of inclusivity and accessibility that allow ordinary people to actively participate in and influence public opinion. In his renowned work The New Public Sphere: Global Civil Society, Communication Networks and Global Governance, Manel Castells examines the shift from “a public sphere anchored around the national institutions of territorially bound societies to a public sphere constituted around the media system” (Castells 2008). He identifies this media system as “a mass self-communication,” which emphasizes many-to-many communication models that circumvent gatekeepers, such as traditional media and government institutions (ibid).

As an extension of Habermas’ public sphere, the networked public sphere signifies a digitally mediated realm where individuals and groups interact and co-construct meaning through networked communication (Benkler 2006; Friedland et al. 2006). It systematically increases “communicative reflexivity at every level of communication,” empowering individuals to actively engage in online discussion (Friedland et al. 2006). The network structure erodes traditional media’s authority and agenda-setting power (ibid). The networked public sphere facilitates diverse communication networks that enrich and nourish debates involving social and political affairs. As such, it broadens communicative spaces for politics and ideology, while providing the capability for individuals from various cultural and geographical backgrounds to engage with and debate one another (Dahlgren 2005).

On the back of digital networks, individuals can swiftly form geographically dispersed and networked publics to challenge the power of mainstream media, while disseminating information and diffusing the protests worldwide (Penney & Dadas 2014). Zuckerman (2020) further explains the power of digital platforms as a political tool for mobilization and advocacy during socio-political crises, which speaks directly to the severe censorship measures enforced by the political leadership and its institutions. For example, while covering Israeli attacks on Gaza, the mainstream media in Western countries have “consistently prioritized Israeli lives over Palestinian ones, adopting Israeli framing and narratives” (Youmans, 2024). In response, young activists and concerned citizens from Palestine and throughout the world use social media platforms to challenge the mainstream narrative and broadcast the other side of the conflict.

The Role of X in Digital Public Sphere

Narrowing down the scope of digital media and political engagement, we now turn to focus on the significance of X (formerly Twitter) as a social media platform that influences public discourse (Majeed and Abushbak 2024). Several scholars examine the role of X within the ongoing conflict between Palestine and Israel. As it relates to the Gaza-Israel border protests on March 30, 2018, Tawseef Majeed and Ali M. Abushbak (2024) argue that X liberalizes Palestine discourse by providing virtual arenas where activists and ordinary users can discuss and disseminate information. They conclude that the microblogging site has been crucial to internationalizing conflict by stating: “The demands of the Palestinian civilians have been able to reach a more global audience via Twitter” (Majeed & Abushbak 2024, p.197). Similarly, Mahmood Monshipouri and Theodore Prompichai (2017) argue that social media has empowered younger generations to influence the public discourse of politics, which highlights the capability of individuals to use and consume, as well as create and produce, information to achieve either their ideological or political purposes.

However, Monshipouri and Prompichai also address the disadvantages of digital media. After the second intifada in 2000, both the Palestinian Islamist movements and Israeli government weaponized social media (Monshipouri & Prompichai 2017). They use these platforms to propagate their ideologies and “counter the new, digital dimension of activism” (Ibid, p.37). Further, while investigating the patterns of X’s actors, Siapera et al. revealed that state actors and non-state actors exploited automated software bots as a strategy to disseminate propaganda and manipulate the digital public sphere (Siapera et al. 2015). With that said, it is necessary to understand that X forms multiple networked publics and connects a broad spectrum of actors that “supersede both the news media and the two antagonists (IDF and Al-Qassam and Hamas) in terms of volume of communication” (Ibid). For example, the authors identify witnesses, who are ordinary users who witness the conflict and share their experiences, as influential emerging actors (Ibid). Within these networks, opinion leaders and influencers emerge to play a role in shaping online narratives.

Existing literature (Xiong et al. 2019; Edingo 2021; Daniele & Kelsch 2025) has thoroughly analyzed the role of X in digital activism. However, this study shifts focus from activism to the broader concept of digital public sphere and networked publics, emphasizing how online discourse is shaped by influential actors across local, regional, and international levels on X. By analyzing the networked publics and themes of these actors, this research offers novel insights into the dynamics of transnational digital conversations surrounding pro-Palestine protests, an area that remains unexplored.

Research Questions

Based on the previous discussion, the paper focuses on addressing the following questions:

- RQ1: Who are the influential actors, both local and international, who dominate the digital public sphere on X when addressing pro-Palestine protests?

- RQ2: What are the dominant themes in the influential actors’ discussions on X?

Research Design: Methodology

This research utilizes a two-stage, mixed-methods approach that combines Social Network Analysis (SNA) and thematic analysis to address the research questions. In the quantitative phase, I use NodeXL Pro to identify influential actors on X based on their structural prominence in networks. Using measures such as in-degree and centrality, I narrow down my sample to focus on the top 30 influencers. These influencers are highly visible in the network and play a crucial role in shaping the digital public sphere. In the second stage, a thematic analysis is applied to analyze the content of the top 30 influencers. In the following section, I will further discuss both methods.

NodeXL Pro is an established SNA tool designed by the Social Media Research Foundation. Using NodeXL, 11,351 X posts (formerly tweets), replies, re-posts, and mentions were extracted, which were published by 8,700 X users from August 16 through December 16, 2024. The keywords used to determine what data would be extracted involved pro-Palestine protests. After extracting networks of nodes (users), they were arranged into groups by cluster, and then grouped according to the dominant conversation moderated by the top influencer. Within each group, there are discussion leaders and active users who frequently post, reply to, or mention pro-Palestine protests (Shneiderman et al. 2014). They are usually located at the center of each network. Moreover, it is likely to find more than one influencer in one group.

This examination identifies the top 30 influential actors by ranking their betweenness centrality and examining their indegree. This study does not restrict the dataset by geographic location. Instead, it adopts an inductive approach to identify online influencers based on the indegree dimension and network centrality. The indegree dimension measures the number of connections each node receives in the network. Further, individuals with a high degree centrality are more likely to be influencers because they occupy “the right network positions” that empowers them to effectively disseminate information and shape the digital public sphere (Liu et al. 2017). As such, their posts will be shared and mentioned among their followers, which circulates this content throughout their network. Meanwhile, betweenness centrality is crucial because it measures the nodes that act as a bridge between disconnected networks or groups. These nodes or X users are often essential to pass information from one group to another and prompt the circulation of a message, which may lead it to go viral (ibid; Smith et al. 2014).

To narrow down the scope of the study, a thematic analysis is applied to examine the content of these 30 influential actors and identify the prominent themes in the digital public sphere of pro-Palestine protests. Although the findings cannot be generalized, a qualitative approach was used to better understand the discourse under investigation. Thematic Analysis (TA) is a method used to identify, analyze, and interpret patterns of meaning within qualitative data. Although Braun & Clarke (2006) argue that TA does not have a unitary theoretical framework, they suggest six phases of analyzing and reporting themes, which aligns with this study’s purposes of tracking the prominent themes. They view the theme as capturing “something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set” (p. 82). The six phases are as follows: first, the researcher should familiarize themselves with the data to understand the depth and breadth of the content. Second, generating initial codes, and this phase aims to sketch and organize the data into meaningful codes/concepts. Based on the research questions, I approach the data and identify potential relevant themes in the digital public sphere of pro-Palestine protests. Third, searching for themes involves merging different codes to form an overarching theme and focusing on analyzing the broader level of themes. Fourth, the reviewing themes phase examines the validity of individual themes in relation to the data set as a whole, excluding those themes that lack enough data to support them. Fifth, the defining and naming themes phase seeks to provide a detailed analysis for each individual theme. The sixth phase is producing the report to include “vivid, compelling extract examples” and “relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature” (Braun & Clarke 2006, p.87). I apply these six phases while analyzing the online themes produced by X users to address, support, advocate, portray, and criticize pro-Palestine protests. In this section, I will include screenshots of some of the original tweets to support my thematic analysis.

Findings and Discussion

Top Influencers: Global Broadcast Hub Networks on X

Using NodeXL, 11,351 posts were extracted from X and placed into Excel. The extraction included information such as the hashtags used in the posts, the date the users joined X, relationships (mentions, replies, and reposts), and the URL for each extracted post. X users relied on several hashtags to discuss, address, report, and document pro-Palestine protests. These hashtags also help to form a network of individuals with shared interests by enabling them to explore different perspectives and facilitating debate or conversation. The leading hashtags in the data under investigation are #Gaza, #Palestine, #freePalestine, #protest, #Israel, #Gazagenocide, and #Germany. These hashtags frequently co-occur with tweets seeking to amplify offline protests and, most importantly, raise awareness of the Israeli aggression against Palestinians in Gaza. Furthermore, the top-mentioned accounts indicate some of the influential actors that will be discussed in subsequent sections.

After extraction, the data was grouped with the Harel—Koren Fast Multiscale algorithm to examine the density of each cluster and its engagement with other clustered networks.

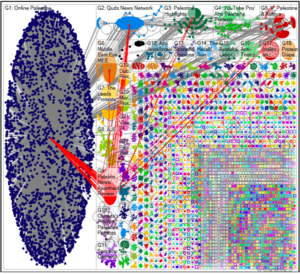

Figure 1: Global Broadcast Hub Networks on Pro-Palestine Protests

Figure 1 displays several networks around the globe that discuss pro-Palestine protests. Each network is formed based on how frequently users interact via mentions or replies to the discussion leader or influencer (Smith et al. 2014). This graph exposes a mixed pattern of network structures, which embody a Broadcast Hub Network and a Clustered Community Network. Broadcast Hub Network refers to the output of news media outlets, which garner heavy interaction from other groups (Ibid). The Broadcast Hub Networks include Online Palestine, Quds News Network, Middle East Eye, Palestine Highlights, Al Jazeera English (AJE), the Herald Sun, and Visegrad. Group 1, which is labeled Palestine Online (@OnlinePaleEng), is among the most influential actors in the digital public sphere regarding pro-Palestine protests. Online users from both the inside and outside of this cluster spread its published content or mention the news media outlet in other clusters, which includes group two (Quds News Network), group three (Palestine Highlights), and group five (V Palestine and Kuffiya). Palestine Online joined X in October 2020 and identifies itself on X as a media and news company that conveys “the voice of the oppressed Palestine people to the world.” It is a verified account that has more than 380,000 followers.

In the same graph, Quds News Network (@QudsNen) is another outlet that extensively disseminates information regarding pro-Palestine protests. Quds News Network is a news network based in London that was established in 2011 to advocate for Palestinians (Quds News Network, 2024). According to their website, they aim to “enhance the Palestinian narrative in cyberspace,” which is achieved by disseminating pertinent information via several social media platforms. These platforms include X where they boast an account (@QudsNen) that has more than 567,000 followers. Interestingly, X suspended the Quds News Network account in 2019 amid speculations the network violated cybercrime law (Al Jazeera 2019).

Palestine Highlights (@palhighlight) is another influential actor in the Broadcast Hub Network, which identifies itself as a Press TV Twitter account that focuses on Palestine. Press TV is an Iranian state-owned news network that was established in June 2007 and broadcasts in English (Press TV 2025). On X, Palestine Highlights is followed by more than 30,000 accounts.

Meanwhile, a Clustered Community Network focuses on trending topics, creating several medium-sized hubs that have their own followers, influencers, and sources of information (Smith et al. 2014). Figure 1 demonstrates that several Cluster Communities were established, such as group five, group seven, group nine, and group 10. For example, within group nine, which is labeled as Palestinian News and Apartheid Review, several hubs are moderated by multiple influencers. These include Palestinian News (@drr_palestine), which identifies itself as a pro-humanitarian activist who advocates for Palestinian rights and criticizes Israel’s human rights violations. The verified account joined X in August 2023 and is followed by around 95 000 users, which it actively engages.

Another hub moderated by Apartheid Review (@ApartheidReview) was launched in February 2023 by Jamie Angeli, a researcher and human rights activist. Apartheid Review focuses on denouncing Zionism and criticizing the U.S.’s unconditional support for Israel by sharing documentaries and visual content from her YouTube channel. Similarly, in group seven, a YouTube content creator dubbed Street Hawk (@streethawks) initiates a cluster that directly addresses the pro-Palestine protests in Leeds, UK. The verified account joined X in January 2023, which is directly after the October 7 attacks and Israel’s subsequent military operation in Gaza. Although Street Hawk has only around 1,000 followers, it actively reports on protests in Leeds and shares YouTube videos they produce. As shown in Figure Two, followers of group nine’s clusters engage with other groups by reposting the content in other networked groups, such as group one, group two, group three, and group five.

Figure 2: Clustered Communities in Group 9

Group 10 focuses on discussing pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protests in Canada. One of the top influencers who moderate the discussion in this group is Caryma Sa’d (@CarymaRules), who identifies herself as a lawyer, journalist, and satirist based in Toronto, Canada. She joined X in November 2016 and has more than 58,000 followers. She extensively reports on clashes occurring at pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protests, which often rely on visual content.

In group five, followers of Kuffiya (@Kuffiyateam) and V Palestine (@V_Palestine20) actively engage and share Online Palestine content. Kuffiya identifies itself on X as a volunteer team seeking to free Palestine by stating, “The way towards a Free Palestine begins with small efforts of small groups.” The account joined X in July 2021 and has around 50,000 followers. Similarly, V Palestine indicates that a free Palestine is one of its goals and adds, “We are on the frontline defending Palestine online” by exposing Israel’s crimes. The account joined X in October 2020 and has 43,000 followers. Both Kuffiya and V Palestine accounts do not have a blue check, which means the accounts have not been verified. They also share their respective Telegram accounts in their bio.

Top Influencers: Broadcast Hub Network Versus Cluster Communities

Based on ranking betweenness centrality and considering high indegree, Table 1 ranks the top influencers from both Broadcast Hub Network and Clustered Communities, which significantly shape the digital public sphere’s narrative regarding pro-Palestine protests. As previously discussed in the method section, betweenness centrality is crucial in identifying nodes that link between weak and strong ties, which act as a bridge between the disconnected clusters. Indegree demonstrates the number of connections each user has in the network. Users with high indegree are more likely to be at the center of the network, which empowers them to disseminate information and influence online public opinion more effectively. This section more closely examines the data to identify a wide range of influencers from both Networks, Broadcast Hub, and Cluster Communities. As such, it focuses on the top 30 influencers by identifying their location, the number of their followers, and the account description.

There are four categories of influential actors who received high indegree and betweenness centrality, which are news media, activists, concerned citizens, and content creators. The last group includes governmental institutions and politicians. All the listed influential actors communicate with followers in English. This is likely related to the keyword used to extract data for this research, which is pro-Palestine protests. The main findings include a broader base of activists, concerned citizens, and content creators that supersede the number of news media outlets. The most influential news media outlets on X are from Iran, Qatar, the UK, Europe, and other unidentified locations. This includes Online Palestine, Quds News Network, Middle East Eye, Visegrad, Press TV, and others.

Additionally, several cluster communities play a significant role in shaping online public discourse by initiating critical debates and providing opportunities for followers to share different viewpoints and engage in discussions. This cluster community includes 13 activists, three concerned citizens, and five content creators. In addition to reporting and documenting, some of these influencers announce the upcoming pro-Palestine protests, as well as advocate for users to physically join the protests. This category contains influencers from the U.S., Canada, Palestine, Ireland, and other unidentified locations.

Table 1: Top Influencers based on Indegree and Betweenness Centrality

| Account Description | Vertex (Username) | Followers | Location | In-Degree | Betweenness Centrality |

| News Media | OnlinePalEng | 385121 | Global | 2893 | 18039582.016 |

| News Media | QudsNen | 566963 | London | 272 | 3149471.799 |

| News Media | palhighlight | 31165 | n/a | 124 | 2642559.634 |

| Social Media | YouTube | 79442201 | San Bruno, CA | 104 | 2331335.690 |

| News Media | middleeasteye | 539896 | n/a | 99 | 1831468.655 |

| Citizen | jomickane | 48930 | UK | 58 | 1275521.940 |

| Content Creator | streethawk0 | 1091 | n/a | 41 | 1174018.655 |

| News Media | ajenglish | 8932779 | Doha, Qatar | 20 | 991037.848 |

| Activist | V_Palestine20 | 42767 | n/a | 52 | 863094.114 |

| Activist | CarymaRules | 58111 | Toronto | 63 | 725153.963 |

| Activist | drr_palestine | 93268 | n/a | 86 | 516729.846 |

| Activist | eyakoby | 63861 | n/a | 14 | 498074.000 |

| Citizen | drewpavlou | 137726 | Brisbane, Australia | 10 | 454252.000 |

| Content Creator | scootercasterny | 71476 | New York | 10 | 339248.000 |

| Citizen | inceptstellar | 4113 | Ireland | 38 | 321876.000 |

| News Media | visegrad24 | 1236007 | Europe | 16 | 303926.000 |

| Activist | sophiabroo53172 | 6268 | U.S. | 34 | 251478.731 |

| Content Creator | marionawfal | 1825886 | n/a | 8 | 250382.000 |

| Activist | mrandyngo | 1599441 | London | 14 | 245846.000 |

| News Media | presstv | 386714 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 14 | 240898.385 |

| Activist | Kuffiyateam | 49084 | Palestine | 41 | 225393.297 |

| Content Creator | redstreamnet | 107952 | Global | 6 | 223338.000 |

| Activist | sahouraxo | 655967 | n/a | 26 | 170898.564 |

| Activist | thestustustudio | 19427 | n/a | 15 | 134424.000 |

| Activist | motherl28134473 | 35465 | San Francisco | 18 | 116546.462 |

| News Media | mailonline | 2850405 | n/a | 12 | 89670.000 |

| Activist | ApartheidReview | 6825 | Sydney,

Australia |

12 | 80855.394 |

| Activist | shaykhsulaiman | 616758 | UK | 9 | 62790.000 |

| Content Creator | truckdriverpleb | 116598 | Canada | 8 | 62788.000 |

| Activist | suppressednews | 460415 | n/a | 7 | 62784.000 |

Qualitative Findings: Positions of Top Influencers- Themes

In this section, the research focuses on qualitatively analyzing the content of the top 30 influential actors—extracted from NodeXL based on the indegree dimension and network centrality—to identify the prominent themes. As explained in the methodology section, indegree measures the number of connections each node receives within the network. Individuals with a high degree of centrality are likely to be influencers as their network position empowers them to effectively disseminate information and shape the digital public sphere. Additionally, betweenness centrality is crucial in measuring the nodes that act as a bridge between disconnected networks or groups.

I applied thematic analysis to analyze the content and posts shared by these top 30 influencers. This allowed for tracking of the emerging dominant themes that shape the digital public sphere around pro-Palestine protests. While the network analysis identifies structurally influential actors on X, the thematic analysis of their posts reveals the dominant narratives in their online discussions. The themes include reporting pro-Palestine protests, documenting police attacks on protesters, featuring clashes between pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protesters, and a critique of pro-Palestine protesters. I use screenshots of some posts to support my analysis.

Figure 3: News Media on X reporting Pro-Palestine Protests

Reporting Pro-Palestine Protests

Several activists and news media outlets extensively report the pro-Palestine protests on X, which include outlets located in France, Norway, Canada, the U.S., Australia, Germany, and across the globe (Figure 3). For example, a Lebanese activist (@sahouraxo) reported on a huge protest in Sanaa, Yemen, which occurred on May 31, 2024. The post received more than 812,000 views, 444 replies, and 13,000 shares. In another trending post dated November 14, the same account reported a massive pro-Palestine protest that opposed Israel’s participation in the 2024 Nations League football match. The post received over 526,000 views, 330 replies, and around 6,000 shares. The Iranian-affiliated news media outlet @PressTV went a step further to post a video clip on November 16, which displayed Israelis attacking pro-Palestine fans during the football match between France and Israel. Attached to the footage is the text, “Here’s how netizens contradicted the mainstream media’s narrative.” Prior to this post by @PressTV, media reported that pro-Palestine protesters had attacked Israeli football fans (Haworth 2024; Times News 2024). The video clip contradicted this mainstream narrative.

On the other hand, @Kuffiyateam states that what is happening in Gaza is a genocide in a video posted on October 7, 2024. This video compiles footage taken from pro-Palestine protests in Ottawa, Canada. The video marks the anniversary of Hamas’ October 7 attacks and Israel’s comprehensive military operation that attacked unarmed and innocent civilians.

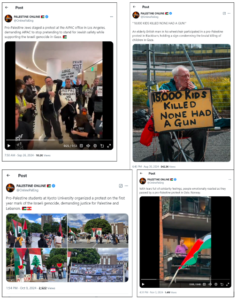

Figure 4: Online Palestine Trending Posts

The account @OnlinePaleEng ranks as one of the key influencers among the news media outlets on X, which frequently covers pro-Palestine protests and receives significant engagement. Figure 4 displays some of the trending posts published by @OnlinePaleEng, such as a video that captures the solidarity and strong emotions generated by pro-Palestine protests in Oslo, Norway. The video was posted on November 3, 2024, and received 1.4 million views, 361 replies, as well as 7,900 shares. Another post published on October 28, shows a protester in Sweden mimicking Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu by wearing a mask covered in blood and holding a baby upside down. The video received 840,000 views, 13,000 shares, and 290 replies. In another post on August 30, @OnlinePaleEng shared a photo of an elderly British man in a wheelchair holding a banner that states, “18,000+ kids killed; None had a gun.” The post was viewed by more than 42,000 users. In another video posted on September 26, the account reported a pro-Palestine protest led by Jewish activists at The American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) office in Los Angeles. The views of this video reached over 10,000.

Figure 5: Online Amplification of Students Offline Collective Action

Similar to the Arab Spring, pro-Palestine protests have observed a domino effect, in which university students orchestrate protests on campus to pressure their universities to cut ties with Israel in response to the Gaza War. Several individual activists and journalists highlight the transnational effect among student movements in different countries in Europe, Asia, and America. For example, in August 2024, a journalist and researcher @IndigoOiver reported that San Francisco State University has responded to students’ demands by “divesting” from weapons manufacturers affiliated with Israel and allegedly involved in the Gaza war, as shown in Figure 5. A few days later, @Unimelb4Palestine, a group of activists and students at the University of Melbourne, posted on X their demands to cut off any academic ties with Israel, referencing one of the university’s joint programs with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI). The first post received over 3000,000 views, 2,500 shares, and 37 replies. The second post received 17,000 views, 216 shares, and 62 replies. Despite the lack of tangible evidence to support the offline collaboration between students in the U.S. and Australia, it is highly likely that students agree on collective action by unifying their demands. Moreover, Figure 5 illustrates further the intertwined relationship between online and offline spheres as individual activists and journalists amplify these offline protests by reporting them.

Figure 6: From the U.S. to Japan on Palestine

Figure 6 reiterates two major patterns in the digital public sphere of pro-Palestine protests, which are the domino effect and the relationship between online and offline protests. In a post published in September 2024, a Japanese citizen @AkinmotoThn spotted that pro-Palestine protesters in Japan use a similar song as their counterparts in the U.S., highlighting that “there is no stopping this global movement from going global.” The post received more than 36,000 views and 828 shares. In another post, an independent journalist @BGOmTheScene reported a protest near the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, quoting a protester as saying: “This is a new generation of activism, and we will be on the streets until we have full liberation.” This post has not received high engagement, though it highlights the process by which X users feature an offline protest, signaling an important message about the new form of activism deployed by pro-Palestine sympathizers and activists.

The theme of the above examples serves to highlight the global solidarity with the people of Gaza and Palestine against Israel’s military attacks. Although Gazans continue to suffer tragic losses at all levels, they won the battle for global public opinion. This was achieved through the collective efforts of students, NGOs, Jewish organizations, activists, and others who mobilized digital and physical protests to pressure the governments and raise awareness among ordinary citizens. Reporting and broadcasting clips of peaceful protests on X served to challenge the mainstream narrative propagated by traditional media and governmental institutions, which sought to distort and misrepresent pro-Palestine protests.

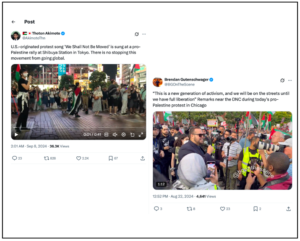

Documenting Police Attacks on Protesters

In addition to reporting on the pro-Palestine protests worldwide, news media outlets, activists, and concerned citizens on X were effective at documenting police violations during protests in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Morocco, and other countries. Figure 5 displays screenshots of several accounts, including @QudsNen, @MiddleEastEye, @redstreatment, @SupressedNews, @KuffiyaTeam, and others. These accounts posted videos and photos of police violence or physical encounters with protesters. The X account @SuppressedNews, which identifies itself as an alternative media company that joined X in January 2012, has more than 461,000 followers. On November 4, this account posted a short clip of German police attacking a woman in response to her verbal assault. In the attached text, @SuppressedNews likened the German police to Iran’s morality police and questioned the violence used by the police against protesters. The post received 73,600 views, 145 replies, and around 1,000 shares.

Figure 7: Screenshots of influential actors documenting police violations

The X account named @redstreatment, which identifies itself as a digital content creator seeking to “empower the oppressed and marginalized people”, frequently posts clips of police violations. For example, on September 21, a widely shared clip shows German police running after a child holding the Palestinian flag during a pro-Palestinian protest. The clip received over 3 million views, 26,000 replies, and 14,000 shares. On October 6, the same digital content creator posted a clip of German police dispersing a pro-Palestine protest and firing pepper spray into the crowd. The clip reached over 60,000 views, received 123 replies and 1,000 shares. In another post published on November 9, @QudsNen posted a clip showing German police dragging a protester.

Other influential accounts posted clips of police violations against protesters in the Netherlands. For example, @MiddleEastEye posted on November 15 a widely shared interview with two protesters who were allegedly beaten by Dutch police. The post received 150,000 views, 388 replies, and over 3,000 shares. On November 10, @QudsNen posted photos of the Dutch police attacking and handcuffing some protesters.

Figure 8: German Police Double Standards

In addition to documenting the violations of German police against pro-Palestine protesters, which was widely circulating throughout the digital public sphere on X, @redstreatment reveals the double standards of the police (Figure 6). On October 21, the account posted a split screen, which showed pro-Palestine protests versus a Nazi march, that illustrated the disparate treatment each event received at the hands of the police. As shown in Figure 6, on the right side of the screen, a police officer physically encountered a veiled woman during a pro-Palestine protest. On the left side, protesters holding the Nazi flag were allowed to march without police interruption. The text caption states, “While German police deploys K-9 units to a pro-Palestine protest, hardline Neo-Nazis are free to march through the city with only a handful of police present…”

The theme of documenting police violations in some Western countries, particularly in Germany, discloses double standards that directly question their values of democracy, freedom of speech, and human rights. The analysis above is consistent with the CIVICUS Monitor (2024) report, which demonstrates the repression of pro-Palestine protests in 2024. Moreover, there was an extensive online discussion regarding German police using excessive force and violence against protesters, which likely explains why #Germany is among the leading hashtags used by X users (Ibid).

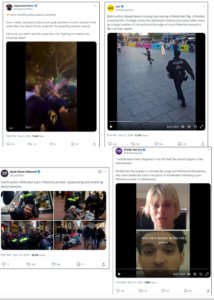

Pro-Palestine versus pro-Israel protesters

In previous themes, the majority of influential actors, which includes news media and activists, positively portray pro-Palestine protests and expose double standards. In contrast, a few influencers focus on highlighting clashes between pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protests and subsequent attacks initiated by pro-Palestine protesters.

Figure 9: Clash between pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protesters

For example, Eyal Yakopy (@Eyakoby) actively advocates for Israel and campaigns against anti-Semitism, while negatively portraying pro-Palestine protesters. His posts garnered traction and circulated widely. For example, a clip published on October 7 shows two girls covering their bodies with the Israeli flags while standing in the face of pro-Palestine protests. The clip received over three million views and 2,300 replies, which were not made publicly accessible by the account. He shared another video from a U.S.-based influential account credited to Oliya Scootercaster (@ScootercasterNy). In the post, @Eyakoby wrote, “two brave Jewish girls stand proudly while a crowd of terror supporters surround them.” The statement is misleading as he labels pro-Palestine protesters as terrorist supporters, while labeling the pro-Israelis as brave for facing the threatening crowd. However, the clip shows that none of the pro-Palestine protesters offended or attacked the pro-Israeli protesters. In another clip posted the same day, @Eyakoby reported the pro-Palestine protest attacked the Head of the Democratic Majority of Israel, which is consistent with the video’s content. However, he continued to negatively portray the pro-Palestine protesters by labeling them as Hamas supporters and domestic terrorists, while also calling for their arrest and prosecution. The post is circulated widely and received 1.8 million views despite the number of his account’s followers being over 73,000.

Critique of pro-Palestine Protesters

Similar to the previous theme, there are examples of activists and concerned citizens devoting their posts to negatively portraying pro-Palestine protests. For example, in a post published on December 3, @DrewPavlou blames protesters for storming a Church in Ireland (Figure 8). Similarly, on August 22, @Eyakoby posted a controversial clip of an interview with a pro-Palestine protester who claimed that he supports Hamas and its attacks on October 7.

Figure 10: Influencers Criticize pro-Palestine Protests

Discussion

Habermas (1974) emphasizes that the public sphere should be inclusive, accessible, autonomous, and involve rational debate. Based on data analysis, the online pro-Palestine discourse on X supports some aspects of Habermas’ theory but challenges others. X is an inclusive platform in the sense that activists, concerned citizens, independent media organizations, and other actors from across the globe participate and share their thoughts on pro-Palestine protests, with a few of them critiquing them.

Despite the fact that influential actors from across the globe used X to amplify offline pro-Palestine protests, it is remarkable to notice the absence of actors in the Middle East and North Africa from participating in the digital public sphere. There are possible reasons that might explain this observation. After the Arab Spring, the regimes changed their policy and acknowledged the criticality of digital media in the sense that they have been using the same tools to counter and suppress any calls for protests, including pro-Palestinian. As Marc Lynch (2021) argues, the MENA’s current public sphere is shaped by “digital authoritarianism,” by which the regimes “invested heavily in ways to control, surveil, and manipulate online activity”(p.5). Put differently, after the Arab Spring, the Middle Eastern regimes perceived the digital public sphere as a threat to their survival; henceforth, they tailored policies to eliminate such a threat and thwart any possible digital activism.

For Palestine, Giulia Daniele and Sophia Maria (2025) explain that Israel’s “cyber colonialism” and “digital occupation” limit and restrict Palestinians from actively shaping global public opinion. Similarly, the current study has observed the participation of a few Palestinian activists on X, and that could be related to Israel’s “digital occupation” or the platform moderation policies or algorithmic bias that seeks to reinforce pro-Israel narratives and downranking pro-Palestine content. Although it is challenging to support such an observation, it is noteworthy that several citizen journalists from Gaza, such as Bisan Owda, Motaz Azaiza, Saleh Al-Jafarawi, and many others, have been actively reporting and broadcasting the violence experienced by Gazans during the war on other social media platforms, in particular TikTok, which played a significant role in challenging the mainstream narratives of the Palestine-Israel conflict. Overall, this indicates that accessibility is limited to those who can freely express their political affiliations without being oppressed or detained by their regimes or occupation forces.

During the Arab Spring, activists strategically used Twitter (Parmelee & Bichard 2011; Breuer et al. 2015; Alimardani & Elswah 202l) as a tool to arrange and organize their protests, circumventing the regimes’ censorship and repression. Similarly, pro-Palestine supporters utilize social media platforms to feature and amplify offline events, demonstrations, and protests, creating a new form of activism. Digital activism, as scholars (Daniele & Maria 2025; Edingo 2021; Castells 2008; Dahlgren 2005) explain, is leaderless protests that rely on a mixed approach of online and offline public spheres. However, in this study, the online public sphere lacks ‘rational debate’, in which pro-Palestine discourse is split into two separate echo chambers, with the bare minimum of interactions between pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protests. The interactions will likely lean towards hostile engagement that fuels hate speech among the two camps, impacting the discussion's rationality and depth.

In this study, digital activism constitutes a counter-public where underrepresented communities speak against dominant narratives. Pro-Palestine advocates, including online media organizations, use X to report the violence experienced by Gazans during the war, a reporting that resonates globally and amplifies the offline protests that reflect global sympathy. Even though pro-Palestine transnational protests lack central leadership, it is possible to observe how student movements in universities in Australia, the U.S., and European countries strategically use a mixed online and offline activism approach to set a common agenda. As shown in the previous section, both the University of Melbourne and San Francisco State University orchestrated efforts to pressure their universities to cut off any academic ties with Israel in response to the Gaza war. However, this could be interpreted as a limited outcome, because it has not significantly changed the foreign policy of any of the Western states towards the Palestine-Israel conflict.

Conclusion

This study aimed to identify the influential actors on X in relation to pro-Palestine protests. Moreover, it examined each account's position regarding Palestine and Israel, as well as the main narratives they promote. Findings reveal that several media organizations—such as Quds News Network, Middle East Eye, and Press TV—extend their roles as influencers in the digital public sphere. Further, there is another emerging and powerful category of news media channel that only exist on digital platforms, such as Palestine Online and Palestine Highlights. Additionally, activists, concerned citizens, and content creators from diverse backgrounds—including Palestine, Canada, U.S., UK, and other unidentified countries—are among the most influential actors who significantly shape the discussions pertaining to pro-Palestine protests. As such, both news media and activists actively shape online narratives. Based on the sample under analysis, the most influential actors on X use the English language while addressing the pro-Palestine protests. This observation might indicate the eagerness of those influencers to target international audiences and communicate their messages worldwide. Also, they heavily rely on visual content to support their narratives.

The examination of content on X that highlights transnational pro-Palestine protests reveals two main camps. The majority of influential actors advocate for global solidarity with Gazans and Palestinians, while simultaneously pushing back against Israeli military operations. These objectives are achieved by framing the pro-Palestine protests in a positive way. In contrast, some influential actors negatively portray the pro-Palestine protesters while praising the pro-Israeli protesters. For example, they label pro-Palestine protesters as terrorists and Hamas supporters, while labeling pro-Israel protesters as brave and peaceful. The number of influential actors in this latter group that this research identified is likely related to the keyword search—pro-Palestine protests—used in the data collection for this study.

The dominant themes that emerged from discussions moderated by influential actors are reporting on pro-Palestine protests, documenting police attacks on protesters, featuring clashes between pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protesters, and criticizing of pro-Palestine protesters. The first theme aims to feature the large protests initiated and led by Palestine advocates across the globe. As previously discussed, it signals global solidarity with Palestinians and aims to pressure governments—particularly in the West—to intervene and demand an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. The second theme extensively documents police violating people’s right to protest, particularly in Germany, while some influencers use these examples to demonstrate the West’s double standards. The last two themes are used by some Israeli advocates to indicate that pro-Palestine protesters are aggressive and violent. They post inaccurate, but widely shared, posts that rely on misleading text that is inconsistent with the video’s content.

Overall, the research highlights the capacity that digital platforms occupy in empowering social media users to influence online narratives and contest mainstream accounts that are propagated by governments and traditional media channels. However, the digital public sphere has limitations. Most importantly, it lacks rational critical debate and dialogue between different camps of ideas and perspectives, which is the core of Habermas’ concept of the public sphere. This deficiency leads to the formation of fragmented networks, which results in like-minded individuals meeting to discuss and consume information that aligns with their beliefs and values. Additionally, the absence of fact-checkers on digital platforms is likely to incentivize the spread of disinformation and misinformation, which may contribute to promoting hatred discourse and divisive communities.

For further studies, the researcher recommends investigating the role of digital media ownership and its impacts upon the policies of social media companies, as well as algorithm controls that can actively amplify or suppress content. Algorithms play a significant role in empowering some voices, while marginalizing others. Such an assumption might contradict the optimistic view regarding the digital public sphere and its capability to maintain a many-to-many communication model, which provides opportunities for individuals to share and communicate their messages with the public openly and freely.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub