It was the go-to pan-Arab newspaper that noted journalists, analysts, and anyone worth their salt wrote for, and that readers seeking professional reporting and deconstructing of events picked up for balanced coverage, diverse views, and hard-hitting editorials—all relatively speaking, of course.

Quite a tall order for a daily in a neck of the woods where press freedom isn’t de rigueur and journalists must often toe the official line, or else.

Today Al Hayat is treading water in Dubai and the Arab Gulf countries after the paper ceased publishing the print editions in the UK, Lebanon, and Egypt this year.

“The destiny of print was all over all and any wall,” said Jamil Mroue, son of the founding publisher/editor Kamel Mroue. “The customer/reader has migrated to the web: Al Hayat is no exception to this flow.”

The glory days seem a distant souvenir.

Word spread in 2017 that the daily intended to shut down its large Beirut bureau in June 2018.

The bureau was established in 1998 in a prime downtown location that also housed Laha, a women’s magazine it owned.

The closure was preceded by a notice to the Lebanese Finance Ministry as a precursor to the planned layoffs and subsequent arrangements for indemnities to staffers. The publishing house had a weekly called Al Wasat that it shuttered in 2004.

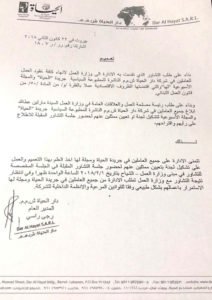

On January 22, 2018, director general Raja Rassi sent a circular to Beirut employees saying the management had informed the Labor Ministry that Dar Al Hayat’s publishing house was terminating the contracts of all staffers at Al Hayat and Laha, due to financial constraints.

Some 100 employees, in both editorial and managerial positions, worked at the Beirut office before the axe fell.

It’s been particularly painful for Beirut bureau staffers given the paper’s birthplace and its journalists’ perseverance under tough conditions over the decades, not least of which was Lebanon’s civil war.

The Lebanon operation had already been teetering on the brink following financial setbacks in recent years. Then came the order to cease the print editions in London, Beirut, and Cairo.

Readers can still browse the paper’s international and Saudi edition websites and download PDF versions.

Dar Al Hayat’s Dubai office has become the new focal point. All inquiries about the state of affairs are referred to Dubai, and staffers in different bureaus are reluctant to discuss matters on the record or on background.

In an interview with Al Ahram Weekly of Egypt, Cairo bureau chief Mohamed Salah said the drawdown and restructuring process had begun in 2016, and that a number of steps had preceded the decision to halt the print editions and close the offices in Beirut and London.

He explained: “The most significant were the plan to develop the website and the launch of ‘Hayat Press,’ a service that adapted the newspaper to social networking journalism or citizen journalism, which is to say it enables numerous individuals to contribute to writing and feeding the news through a social networking platform. It is like an interactive news agency and it is part of the single newsroom operated out of Dubai.”

The result has been a weak cocktail of content. On many days I saw stories written by the amateurs duplicating what the regular reporters had produced, often competing with them on the same page.

It’s a far cry from what the founder, his son, and subsequent editors had maintained as a standard.

Kamel Mroue launched Al Hayat in 1946. He paid the ultimate price when he was assassinated in his office two decades later because of his outspoken journalism.

The paper carried on until Lebanon’s 1975-90 civil war got in the way. It ceased publishing in March 1976.

“I relaunched Al Hayat in 1986 in partnership with Khalid bin Sultan,” said Mroue, referring to the Saudi prince whose late father was then the powerful minister of defense.

The arrangement was for the creation of a shell publishing company called “Brass Tacks” in which Prince Khalid owned 75% equity, Mroue had 24%, and future editor Jihad Khazen was allotted 1%.

Khazen, on behalf of the prince, got to own the 1% on the merit of arranging the deal between Mroue, his brothers Karim and Malek, and Bin Sultan. He functioned as the middleman fixer.

“’Brass Tacks’ signed a publishing contract with Al Hayat (owned by Karim, Malek, and myself) for the purpose of (the) relaunch,” Mroue said.

Unlike other regional publications, there were no restrictions on what the paper could publish and cover, bar (predictably) news and opinions about Saudi Arabia, and, to a slightly lesser extent, former president Hosni Mubarak's Egypt, Mroue said.

Mroue took the helm and began producing the paper in London as the Lebanese civil war made working out of Beirut difficult.

“I was the editor because I had planned the concept, gathered the team and set the policy of relaunching Al Hayat,” he explained.

But when the prince was appointed joint commander (along with U.S. General Norman Schwartzkopf) of the allied forces during the 1991 Gulf War, following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, Prince Khalid expressed his "need" to be in total control of the newspaper.

“As the editor (perhaps as a person, too), I was not considered totally trustworthy to be editor of a Saudi-owned paper,” Mroue said. “Khazen was appointed when in 1993 (after months of wrestling), we (my brothers and I) resigned to the fact and conceded to ‘lease’ the brand name Al Hayat.”

Mroue divested his shares in “Brass Tacks” for free. The lease was valued at $300,000 annually for ten years, which was to be annulled upon the forced bid by Prince Khalid to own all Al Hayat in 1996, he added.

But that didn’t save the paper.

“(It) goes without saying, that the transition from print to the web is not a natural metamorphosis: creating a web presence demands more planning, different creativity, and a radically shifted content and tech scale, than print,” Mroue noted. All this Al Hayat has not done with commitment.”

Additionally, today the other Saudi-owned pan-Arab daily Asharq Al-Awsat just happens to fall under the wing of Crown Prince Mohamad Bin Salman, so it benefits the most from that patronage.

I asked Mroue what had afflicted newspapers in the Arab world, and why Al Hayat couldn’t be sustainable and have a viable business model that evolved with the times, given its solid reputation and good journalistic coverage over the years, albeit under Saudi ownership.

His reply: “Media in the Arab world rarely engaged the reader. There are exceptions of course, but they are few and far between, in time and place.”

Despite his disappointment, Mroue wasn’t over with media, although he hadn’t planned on delving into journalism growing up.

“I may never have become involved in the newspaper business if I was not catapulted into it by the tragedy of my father's assassination,” he said. “At school, I was ‘gifted’ for maths and sciences; I likely would have taken a career track in the science or engineering domains.”

His father had also established the Beirut-based newspaper The Daily Star in 1952 and an umbrella company that included a marketing and research firm, and a public relations enterprise.

So in 1996 Mroue decided to relaunch the only English-language broadsheet—on hiatus during the civil war—with the seed money acquired from the forced sale of Al Hayat, and again, initially assumed the editor's role because he had developed the concept and gathered the team.

“Also, there was the consideration that in Lebanon I must anchor the political responsibility for the newspaper,” he said.

The Star gained a footing in the Lebanese market and earned a financially sufficient share to keep going, he said.

But in 2000, Mroue went further and seized the opportunity to twin with the International Herald Tribune (IHT), then owned by The New York Times and The Washington Post, to publish across the Arab Middle East.

That led to lucrative co-publishing contracts with newspaper publishers in Kuwait, Qatar, Egypt, and the UAE.

Enter the Internet, which in 2005 began proliferating far and wide in the Arab region, and the benefits from the co-publishing agreements began to dry up.

A year later disaster struck when the Lebanese party Hezbollah kidnapped and killed Israeli soldiers in a cross-border raid triggering a 33-day retaliatory war that destroyed much of Beirut’s southern suburb, many parts of the country’s south, crippled infrastructure, and nearly brought the economy to its knees.

That’s when the serious advertising drought set in, Mroue said.

“The Star pioneered the drive to take the paper on the Internet,” he recalls with pride. “Perhaps we were the first to start a seriously dedicated web edition, and it was a resounding success in comparative terms. “

The IHT web people and The Washington Post's folks were still mulling their web destiny and the online business model had not even been contemplated, let alone as a revenue stream.

“So, the fat accrued from the co-publishing agreements was burning up progressively and aggressively,” Mroue said. “I tried for three years to bring in capital by selling equity, to no avail.”

That left him with little choice: either concede a slow death or leave the enterprise in hands that were better financed. By 2010, he sold The Daily Star to Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

The demise of Al Hayat’s print edition for international readers, and the paper’s shrinkage has come on the heels of severe cutbacks in Lebanon’s media.

Assafir, a 43-year-old daily which emerged during the civil war and became a strong competitor to existing fare, bit the dust in December 2016, despite repeated infusions of funds from assorted patrons.

Al Itihad Al Lubnani, a broadsheet that was revived after years of slumber under different management to compete against already economically hobbled print media, published its final issue in mid-December 2017, a mere two months after its launch.

Prospects are dim. Other papers aren’t doing so well either, leading to countless layoffs and lawsuits in Lebanon on charges of “arbitrary dismissals.”

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub