Abstract

This paper, as a part of an on-going research project, examines Daesh's media (2014-2017) and seeks to provide a deeper understanding of how Daesh spreads its messages. It focuses on the importance of media as one of the main factors behind Daesh’s power. It also demonstrates that in order to export a powerful self-image to the outside world, Daesh considers media a significant part of Jihad, and consequently perceives the media war as equally, or even more important than the military war. In this process, Daesh relies on its own media to spread its content, while mainstream media enthusiastically release the news relevant to Daesh. Besides studying Daesh’s media, this paper highlights the importance of ‘message’ for Daesh: to present itself as a powerful and a victorious actor, while seeking to portray a weak and coward-like picture of its enemies to the outside world. This paper also examines the group’s communication strategy.

Introduction

This paper studies Daesh’s media, considering it as one of the main reasons behind its power since June 2014. It draws on Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, which is defined as ruling by consent rather than by force. Gramsci considered ‘media’ as a part of hegemonic power, besides church, schools, and trade unions, which create consent among people (Gramsci 1973). Besides creating fear among its people through coercive institutions, tools, and methods, Daesh has used media, schools, and mosques to govern its people through consent (Kadivar 2020b). The focus of this paper is on Daesh’s media, as important means, which Daesh has used to infiltrate people’s mind and hearts.

To Daesh, the real war, which is parallel to, if not greater than military war, is the media war (Media Man, You Are a Mujāhid Too 2015a; 2015b). Since Daesh believes the war against Islam and Muslims occurs through the media, as a means to transform the identity of the Ummah (Muslim Community) and to distort Muslims’ beliefs and values, it has invested in media activities to counteract enemy propaganda (Media Man, You Are a Mujāhid Too 2015a; 2015b). Therefore, in parallel with its military attacks and acts of terrorism in different countries, Daesh has placed a priority on developing a sophisticated communication strategy, and has increased its use of various media as important psychological warfare tools.

There is a large body of literature about Daesh’s media activities. Some scholars such as Winkler, et al. (2016) follow the deterministic approach and have built on McLuhan’s (2005) insight that “the medium is the message”, and in this case argue that “the medium is terrorism” (Winkler et al. 2016, 14-15). Unlike the mentioned approach, this paper follows a nondeterministic approach to examine Daesh’s media, and considers its media as one factor next to other cultural, political, and economic elements that have increased Daesh’s power. It also emphasizes that Daesh's media should not be examined as an isolated phenomenon, but should be studied through perspectives of global Jihad, Salafi-Takfiri ideology, and political circumstances.[1]

The main methods used to collect data in this study are archival research, desk research, and semi-structured interviews with experts familiar with Daesh’s activities in different countries.[2] This paper is organized as follows. Firstly, I examine the importance of media, and explore the various media produced by Daesh (since 2014) to understand how the group circulates its messages among its diverse audiences and creates consent among its people. Consequently, Daesh’s media strategy, its propaganda system, and the methods that it has used are studied respectively.

The Importance of Media

Since Daesh’s inception in June 2014, in order to effectively release messages, engagement with different types of media has been a significant part of their communications strategy. Daesh believes that the importance of the word is considerable (Majmou Rasa'il wa Moallafat Maktab Al-Buḥuth wa Al-Dirasat 2017, 1082), so, “media play a bigger role, as kuffar capable to enter in all homes and rooms through satellite dishes” (Majmou Rasa'il wa Moallafat Maktab Al-Buhḥuth wa Al-Dirasat 2017, 2703). Daesh has formulated offensive and defensive ‘information Jihad’ as significant parts of its battle against its enemies (Media Man, You Are a Mujāhid Too 2015a; 2015b), and has claimed that “words [are] sometimes more powerful than the atomic bomb” (Media Man, You Are a Mujāhid Too 2015b, 11). One of Daesh's senior media officials claims that “jihad in the media is half of our war, if not the majority, and the media men's activities were parallel, if not greater than, the military activities” (Media Man, You Are a Mujāhid Too 2015a).

For this reason, Daesh has noticeably invested in its media activities, and has targeted people inside and outside its territory. Therefore, ‘media’ and ‘message’ both have been important factors for Daesh's power. Daesh’s media “tend to be precise, credible, and very professional, which was not the case to similar groups” (Hashim, PI 2017). That caused its official texts to be considered seriously by its opponents and enemies. Besides offline media activities inside its territories, putting up billboards and providing Neghat Al-A’alamieh (media points or kiosks) with materials to disseminate, diverse digital media platforms have provided the capacity to directly reach its target audiences around the world.

Although one of the important functions of media for Daesh is communication, it is not limited to this role only. As Nayouf (PI 2017) points out, “they have exploited more than any man or political movement in the West all the possibilities of web 2.0.” Daesh has therefore benefited from its media to achieve different cultural, political, and economic objectives, including: disseminating its propaganda via various texts; recruiting and obtaining more supporters; defending the Khilafah (Caliphate); representing its Khilafah as a utopia; threatening and intimidating enemies and opponents; gaining public trust, particularly among the Sunni Muslims; fundraising; marketing; communicating with supporters; spreading news; mobilizing its advocates; increasing religious and political polarization.

According to the “3 Years on the Islamic State” (2017) infographic, which was published by Yaqeen Media Telegram channel, one of Daesh's unofficial affiliated media, from June 2014 to June 2017, Daesh released 41230 types of content, including 1670 audio releases, 2880 video releases, 4540 text releases, and 32140 photo releases. This infographic shows 46 official media offices among Daesh's media achievements.

Figure 1. Three Years on the Islamic State (Yaqeen Telegram Channel)

The tools and platforms that were used by Daesh and its supporters differed based on their popularity, usefulness, and security in a given geographical area. For example, Saleh (PI 2017) explains different off and online ways of recruitment in various regions and notes that in Muslim societies, recruitment is based mainly on intermediaries of clerics and NGOs. In the West, however, recruitment is done by sending messages to the person themselves by the organization’s accounts on Facebook and Twitter, communicating with the person electronically through a relative, or a friend within the Islamic State invites them to immigrate to it and provides them with the required instructions.

While Daesh, like other Salafi groups, uses media in presenting its ideology, it outperforms other active Takfiri groups in understanding the significance and potential of the media in releasing propaganda.[3] In this regard, Fallahpour (PI 2017) argues, other groups are mainly passive and their use of the media is a response to the false claims made by Western media rather than a significant component of their overall strategy.

To understand how Daesh disseminates its messages, the next subsection discusses its various media organizations.

Daesh’s Media Organizations

Since Daesh's main media rule is “don't hear about us, hear from us,” (Weiss and Hassan 2015, 174), a direct examination of its media organizations seems the most appropriate way to figure out how Daesh circulates its messages.

Besides different institutions, including the family, mosques, and schools, as the primary reference groups that create consent, meaning, and identity (Kadivar 2020b), Daesh has used various online and offline media to spread its messages. Daesh has attempted to capitalize on all opportunities to disseminate propaganda and stop any kind of counterpropaganda to influence a much larger audience. Using this strategy, Daesh created an environment in which people accept its messages more easily and consider these messages as fact, and spread fear amongst enemies constantly.

The Diwan of Media is the body responsible for any content released by Daesh, whether that content is audio, visual, or written. It announces the main media principles and duties, and defines the priorities of publication and broadcasting (The Structure of the Khilafah 2016). Daesh’s media can be categorized into official and unofficial media. Almost all official online texts have also offline versions, which are distributed among locals.

Official Media

The main official media producers of Daesh, according to The Structure of the Khilafah (2016) are the Ajnad media foundation, Al-Hayat media centre, Al-Furqan media foundation, Al-Bayan radio, Al-Naba newsletter, Al-Himmah publication, and local media offices in different provinces. Also, Dabiq, Rumiyah, French magazine Dar al-Islam, Turkish magazine Al-Qustantaniyah, and Russian magazine Istok (Al-Manba) are among the official magazines of Daesh.

Figure 2. Daesh’s Official Media

Al-Munasirun (Supporters) and the Languages and Translations departments are two significant branches inside the Diwan of Media.

The Al-Furqan Media Foundation

The Al-Furqan Media Foundation, the oldest media branch of Daesh, started its activities in November 2006. Initially, it was responsible for media production for the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) releasing official statements, various videos, CDs, DVDs, posters, pamphlets, and web-related propaganda products (KhilafaTimes 2015). Since 2006, Al-Furqan has released different official statements and audio messages of Daesh and its predecessors’ leaders. Video of Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi’s Khutbah (sermon) during Friday prayers at the Grand Mosque, Mosul, July 4, 2014, was released by Al-Furqan Media. Al-Furqan released the latest recorded speech of Daesh’s spokesman Abu Hamza Al Quraishi's on October 19, 2020.

The Al-Hayat Media Center

The Al-Hayat Media Centre was established in mid 2014 (KhilafaTimes 2015). It has distributed Daesh’s propaganda, such as videos, magazines (Islamic State Report, Dabiq Magazine (mostly in English), Dar Al-Islam Magazine (in French), Al-Manba’ Magazine (in Russian), Al-Qustantiniya Magazine (in Turkish), and Rumiyah Magazine (in different languages), MujaTweets, and nasheed clips.[4] All Daesh magazines have been discontinued without any announced reasons. The End of Sykes Picot (2014), The Dark Rise of Banknotes and the Return of the Gold Dinar (2015), Inside the khilafah 1-8 (2017), Flames of War I- II (2014, 2017) videos and For The Sake of Allah nasheed (2015) are among the most important productions of Al-Hayat media. Al Hayat Media promoted a video last year calling on supporters to carry out arson Jihad (Incite the Believers 2020). Al-Hayat has mainly targeted Western audiences.

The Ajnad Media Foundation

The Ajnad Media Foundation is one of the official media wings of Daesh, which produces Daesh’s nasheeds and Qur’an recitations. It was established in January 2014 and specializes in audio productions. It has released more than 150 nasheeds, such as Salil al-Sawarem (2014), Shariat Rabbuna Nouran (2014), Ghariban Ghariba (2015), Ghamat Al-Dawalah (2016), Dawlati Baqiya (2017), Dawlati la Tuqhar (2017), Rayat Al-Tawhid (2018).

The Al-Bayan Radio

The Al-Bayan was Daesh’s official radio station, it started its activities in 2014. Daesh ran the FM radio station Al-Bayan, which broadcast news of the Khilafah. Radio news bulletins in Arabic, English, and some other languages were also distributed through social media, especially in different Telegram channels in audio and texts. The Al-Bayan Network radio station covered official messages, general news of military operations in various provinces, religious programs, nasheeds, Fatwas,[5] interviews, along with other reports regarding the organization. A considerable archive of Daesh’s ideological audios that were released by Al-Bayan is still available in different platforms and several of them, such as Silsilat al-Ilmiyyah fi Bayan Masai’l al-Minhajiyyah (Scientific series in the statement of methodological issues 2017) were published as books in recent years.

Dabiq magazine

Al-Hayat began publishing Dabiq magazine in Ramadan 1435 (July 2014). After two years of being active and releasing 15 issues in the process, in September 2016 Daesh stopped Dabiq publication and replaced it with Rumiyah. Every issue of Dabiq contained Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s (Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad leader) quote: “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify – by Allah’s permission – until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.” (Dabiq 1-15 2014-2016, 2)

Rumiyah magazine

Rumiyah was a monthly online magazine. Its first issue was published in September 2016. Rumiyah replaced Dabiq, Dar Al-Islam (a French online magazine) and other magazines. Rumiyah was published in different languages, such as English, French, German, Pashto, Russian, Turkish, Indonesian, and Uyghur (Khilafatimes 2016) by the Al-Hayat Media Centre. Since its release, each issue opens with a quote by Abu-Hamza Al-Muhajir, Amir of the Islamic State of Iraq (2006-2010): “O muwahhidin, rejoice, for by Allah, we will not rest from our jihad except beneath the olive trees of Rumiyah (Rome)” (Rumiyah 1-13 2016-2017, 2). On September 9, 2017, Daesh released the 13th edition as the final issue of Rumiyah.

The Al-Naba’ Newsletter

Al-Naba’ is an Arabic weekly newsletter on provincial military activities and regional events by Daesh (KhilafaTimes 2015) and is still, at the time of publication of this study, published weekly. It is published regularly (every Thursday) by the Diwan of Media, and includes news, analysis, infographics, religious content including fatwa, and advertisement of other media productions, among others. It is published in both print forms and online, and distributed in different places simultaneously.

Figure 3. A fighter reading Al-Naba' newsletter

Its publication has developed through seven stages since 2011. According to Al-Naba’ issue 1 (2015, 2) these stages are:

1-The first issue of Al Naba’ was published in Jumādá al-ākhirah 1431 (May-June 2010)

2- Al Naba’ became a monthly newsletter in Jumādá al-ākhirah 1432 (May-June 2011)

3- Its first Weekly Statistics were issued in Dhū al-Ḥijjah 1433 (October-November 2012) including 4500 documents in 198 pages and its second Weekly Statistics were released in Dhū al-Ḥijjah 1434 (October-November 2013) including 7981 documents in 410 pages.

4- Al Naba’ published news of Wilayat Sham in Rabī‘ ath-thānī 1434 (Feb-March 2013). Al Naba’ Issue 39 was its first issue after announcing Islamic State of Iraq and Sham.

5- Al Naba’ became a semiweekly newsletter in 1435 (2013).

6- Al Naba’ altered to a weekly newsletter on 16 Shawwal 1436 (Aug 2, 2015), published political articles, photos, and the announcements of Diwan Media publications.

7- On 3 Muharram 1437 (17 Oct 2015) Al-Naba’ started its activity as an official weekly newsletter (Al-Naba’1, 2015, 2).

Figure 4. Seven stages of publishing Al-Naba’

Maktabat al-Himmah

Maktabat al-Himmah (Al-Himmah publication) is one of the most important official sources of Daesh’s propaganda that produces content for various audience groups. It has released different types of content, ranging from wall posters and billboards (for example about Jihad, Hijab, shari’ah law, promoting Daesh as a functional state, Remaining and Expanding), brochures, and books (such as Fiqh al-Jihad or the Wahhabi texts) to small leaflets about different issues (such as slavery, Zakat, Jihad, Fasting, and Hijab). It also released an app that teaches children reading and writing Arabic.

Figure 5. One of the Al-Himmah publication’s leaflets

Despite the closure of several written media, such as Dabiq and Rumiyah, the Al-Himmah publication has remained active and produces various types of materials in different languages for its audiences. However, with the defeat of Daesh in Iraq and Syria, the distribution of its offline materials is difficult; its online content is still circulating by Daesh supporters and members on various platforms.

Provincial Media Offices

Each province has its own media office, which is in coordination with the military and security officials in the region. According to Al-Masri (2015) its director should be in direct contact with the media official in the Base Foundation. These media offices have produced content related to their local areas, including news, photos, videos, and nasheeds. Millat Al-Kufr Wahidah (Al-Kufr is one Religion), Jayl Al-Khilafah (Generation of the Caliphate), Ummato Walud (The Fertile Nation) (1-5) are among the most significant videos produced by the provincial media offices. On Jan 8, 2021, Wilayat Sinai released its newest video, Nazif Al-Hamalat (Bleeding campaign), which was about IED attacks, kidnappings, and executions.

Figure 6. The Fertile Nation 4 (Wilayat Raqqa)

There are also several important media, such as Al-Itisam, Amaq, and Nashir that were not mentioned as Daesh’s official media by its authorized official centres and productions. However, many experts have considered them as significant as other official media in Daesh’s propaganda activities.

The Al-Itisam Media Centre

The Al-Itisam Media Centre is one of the most important media wings of Daesh, and has produced and distributed propaganda videos since it was formed in 2013. According to Stern and Berger (2015, 153), Daesh set up its first official ‘media foundation’ under the name al-I'tisam. The announcement of Al-Itisam media centre—affiliated with the Islamic State of Iraq—was issued by the Global Islamic Media Front (E'elan an Nashr Mussisat Al-I’tisam 2013). Al-Itisam has produced many high-quality videos, such as Nawafidh ala Al-Ard Al-Malahim (Windows on the Land of Epic Battles 2013-2014), Kasr Al-Hodud (Breaking of the Border 2014), and Risalah Al-Mujahid 1-5 (Message of the Mujahid 2014). (Al-Itisaam Media 2014)

The Amaq News Agency

Beside the above official media, the Amaq news agency, which is considered Daesh's mouthpiece, is among its important media, and is used to ‘break news’ about Daesh’s activities. Amaq was launched in 2014. It had a WordPress-based blog, which was removed in April 2016, and later continued its activities on Telegram. Amaq publishes short news texts, photos, audios, and videos. Its name was not mentioned in The Structure of the Khilafah (2016) video as one of Daesh’s official media outlets though. However, as Mustafa Al-Iraqi (2107), one of Daesh's supporters active in the English Telegram channel CALIPHATE_MEDIA, notes:

Amaq Agency is ‘official’ but at the same time ‘unofficial’. Because:

1: It’s run inside the State

2: It’s run by State officials

But at the same time, when Islamic State mentions their official medias … they never mention Amaq. And another difference between official reports and Amaq reports: Islamic State uses Islamic terms or names they themselves renamed.

Example of official reports: When naming their enemies: Rāfidhah, Nusayriah, Sahwāt, Crusaders, Mushrikin etc. Names of places: Renamed Deir Ezzor to Wilayat al-Khayr, Hasakah to Wilayat Barakah.

While Amaq reports are more ‘political’ like: Shi’ah, Syrian regime, Syrian rebels, Americans, Christians, and they don't use the State's renamed provinces but uses the original.

The Nashir News Agency

The Nashir news agency forms another propaganda arm of Daesh. It publishes photos, videos, audio, and short news in different languages. The tune of Nashir’s content is completely different from Amaq. It also republishes Amaq and other content produced in the provinces.

Figure 7. Nahir News agency Telegram Channel

As the above logo displays, Nashir introduces itself as “Specialized in the official news of the Islamic State Caliphate.”

Unofficial Media

There are many unofficial media associated with Daesh, including Al-Battar, Al-Yaqeen, Tarjumān al-Āsāwirtī for Media Production, Fursan Al-Balagh Media, Halummu, Alghuraba Media, Remah Media Production, etc. There are also thousands of private accounts of individuals in different platforms that were followed by thousands of Internet users (Munaserin), which have a significant role in spreading Daesh's propaganda. Moreover, Daesh has used traditional Internet sites and web blogs for broadcasting news in war fronts, organizational announcements, and ideological objectives.

After losing most of its territories in Iraq and Syria, the number of Daesh’s content decreased considerably, and Daesh's own survival overshadowed different proceedings, including its media activities. However, Amaq and Nashir news agencies, several official (such as Al-Naba, Al-Furqan, Wilayat media, and Al-Himmah) and unofficial media remain active (as of the publication date of this study) and produce content, which indicates that Daesh still seeks to portray a powerful self-image to the outside world by its media in spite of the defeats it suffered on the battlefield. For example, two-three days after Netflix released a film entitled Mosul (2020), Daesh’s supporters released a video entitled Al-Mosul Rewayat Al-Ukhra (Mosul Another perspective) (2020), with a Netflix logo, focusing on the takeover of Mosul from Iraq. It displayed Daesh as a victorious and powerful actor, supported by the local population. The main point of this video is that people were happy about Daesh's takeover. Another example is the publication of Sawt Al-Hind (Voice of Hind) magazine by a pro Daesh media group in India (2021).

The Media Point (Kiosk)

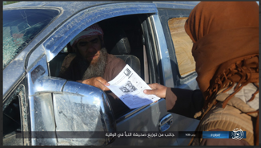

Media points (Neghat Al-A’alamieh) play the same role for Daesh in the real world, as different online platforms play in the virtual world, which is to disseminate Daesh’s propaganda to its target audiences. They are the links between the public and Daesh’s media, which are established by media offices in different areas under Daesh control.

Figure 8. A media point in Wilāyat Barakah

Daesh established a network of media kiosks across Iraq and Syria, which targeted people in all age groups. In June 2017, ‘Yaqeen Media’ – a pro-Daesh Telegram channel – released an infographic about Daesh’s accomplishments in different areas since June 2014 and estimated that there are 1000 media points in the Khilafah.

Winter (PI 2017) explains that “these range from open air cinemas to mobile kiosks, there'll literally be a minivan with a printer and a wide screen TV in the back.” Daesh also expanded its media points from booths to mosques and hospitals in Iraq and Syria. Additionally, Daesh has set up an integrated media archive at the media points in different languages (for example: from English, French, and Kurdish to Turkish, Farsi, and Bangla) as a resource for the public (Al-Naba 21 2016, 12). The media point has been a media and summons (da’wah) project that distributes different kinds of information to the ordinary people, which they then circulate through means such as cell phones, flash drives, and CDs. Another purpose is to distribute Daesh’s newsletters, magazines, books, pamphlets, announcements, and flyers. The media points are also used for screening films that document the current fights (Ibid.).

Daesh has also created mobile media points to deliver its content to remote regions. Using these media kiosks, Daesh delivers its own narrative to the locals. As Winter (PI 2017) stresses: “they are in symphony with a policy of creeping censorship whereby the Internet and satellite televisions were removed from the local civilian population.” He explains that a very important part of Daesh's offline propaganda strategy came in the form of direct engagement, with media officials walking around, talking to people, handing out da’wah materials and new propaganda releases, handing out sweets, and holding spectacles in town squares (Winter 2017).

Figure 9. A media point in Wilāyat Nīnawā

Studying media points indicates their important role in indoctrination and creating consent among local people inside the Khilafah, who did not have access to other kinds of media under Daesh’s rule.

Next, Daesh’s effective and sophisticated communication strategy will be investigated.

Daesh’s Media Strategy

Similar to other global actors, and consistent with Gramsci’s writings, Daesh's activities have been based on ‘consent’ and ‘coercion’. To create consent and fear and in order to advance its aims, Daesh has employed a sophisticated media strategy. Based on its main motto ‘remaining and expanding’, which has been repeated in different official statements and media content (such as: Al-Adnani 2015a; 2015b; Al-Nabā 34, 2016:3; Dawlati Baghiya 2017), and besides its military strategy, Daesh's media have been focused on producing diverse propaganda texts and techniques to show itself as: a powerful actor; communicating its ideology; neutralizing enemies’ propaganda; intimidating adversaries; encouraging new recruits to the Khilafah territories.

Daesh has used diverse propaganda methods and platforms to expand its power and spread its messages through its media far beyond its borders. It believes using more platforms, accounts, and channels increases its effectivity, helps it grow faster, and portrays a stronger picture to audiences. In its media activities, Daesh has learned many lessons from other Salafi-Takfiri groups to be self-reliant. As Nayouf (PI 2017) highlights:

Daesh is far from having invented everything. The jihadist filmography begins with the war in Afghanistan, continuing to improve in visual and technical quality, then expanding the means, themes and places of jihad (Bosnia, Algeria, then the wave of attacks of Al-Qaeda...). Using the international media (including Al-Jazeera), the Salafist video library is gradually challenging the monopoly of the image of Westerners. Al-Qaeda already had its news agency... In 2010, Al-Qaeda launched ‘Inspire’, the first online jihadist magazine, written entirely in English...

Daesh also learned from other non-Muslims countries, for example China and Cuba. In this regard, Ingram (2015) explains “the core mechanics of Islamic State communications strategy are broadly reflected in the writings of Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh and others.” Furthermore, Daesh adopted the strategies used by several leading social media figures, such as being intimate (like Katy Perry), networking (like Taylor Swift), and starting arguments with other high-profile figures, which then draws further attention to himself (like Donald Trump) (Singer and Brooking 2015). El-Meshoh (PI 2017) stresses, “The Islamic State did not invent something ‘extraordinary’. They merely used the tools and technologies available to everyone, even amateurs.” With that said, Daesh has pursued the strategies outlined below in its media to find more audiences for its messages.

Media Activity as a Part of Armed Activities

Daesh has improved its media strategy alongside its military strategy and has viewed its battlefield as broader than the ground upon which it fights. Daesh's media operatives have been present in the battleground beside the soldiers, and have produced videos, audio, written texts, photos, and news. Without their activities, Daesh would not be able to release its first-hand content depicting its combat. According to Daesh, media activity is a Jihad in the way of Allah, which has extensive potential to change the balance with respect to the war between the Muslims and their enemies, and is more powerful than a nuclear bomb (Media Man, You are a Mujahid too, 2015a; 2015b). It also considers every media operative, with their media works, as mujahid in the way of Allah (Media Man, You are a Mujahid too, 2015a; 2015b)). As Al-Hashimi (PI 2017) mentions, “Daesh has a media arsenal. A clever media discourse that seeks to intimidate its opponents and inflict the most psychological damage to their soldiers, leaders, and social and political incubators.”

Figure 10. A fighter with a head camera in the battleground

Because of this close relationship between media and armed activities, there is a direct relationship between the quantity and quality of Daesh’s media productions and its activities in the battleground. For example, the rate of Daesh's productions has reduced since its military defeats in 2016 and the death of its key media strategists. Nevertheless, it still has enough content to spread fear among its enemies and bring back hope and consent to its supporters. To release its propaganda, Daesh, unlike any group before it, commanded an online army of great magnitude and effectiveness (J.Magnier, PI 2017). At the highest level, it recognized the importance of using cyberspace to weaponize the media and spread its story widely (Bartetzko, PI 2017; Winter, PI 2017).

Effective Propaganda System

Like other successful propagandists, Daesh has used propaganda as a form of communication and persuasion to create consent, manipulate views and attitudes, influence behaviours, and manage public opinion to encourage or discourage certain forms of behavior. Furthermore, Daesh has employed propaganda as psychological warfare to confuse, mislead, demoralize, and dehumanize enemies; to win the sympathies of the population; and to create hatred towards foes.

Daesh has also made its propaganda eye-catching, consistent with the dominant beliefs of its people, and in line with their demands for change. It has used different kinds of signs and symbols in its propaganda such as words, slogans, heroic and attractive nasheeds, flags, clothing, and religious designs on its coins to convey its messages and to influence its diverse audiences.

Through its propaganda, Daesh has tried to recruit more fighters and attract more supporters outside its Khilafah (Ramadan, PI 2017; Saleh, PI 2017; Shaban, PI 2017). It has also sought to alienate, manipulate, and indoctrinate its people to influence their opinions or behaviors, and create consent among them (Al-Hashimi, PI 2017; J.Magnier, PI 2017). Moreover, Daesh’s propaganda has attempted to nullify its opponents’ acts and to terrify its enemies (Al-Tukmehchi, PI 2017; Hashem, PI 2017). Another aim of Daesh's propaganda has been to spread its news and transmit its ideological views to larger target audiences (Ramadan, PI 2017; Shabaan, PI 2017; Ornek, PI 2017; Ontikov, PI 2017).

In testimony, a former member of Daesh’s security apparatus stressed their tendency to lie in their media (Al-Iraqi 2019, 8), and explains two important methods of its media:

-

Improving the image of the 'Dawla', and portraying it as just and pious for those inside it generally and those outside it in particular, so that they would be able to draw in the monotheists thirsty for the law of God from different regions outside the 'Dawla'.

-

Showing the claimed force and might of the 'Dawla' – … in order to deceive the Muslims living in the lands of the 'Dawla' and outside it that the 'Dawla' is invincible, and that everything is under control, so they should not worry! (Al-Iraqi 2019, 8)

Al-Iraqi explains another of Daesh’s propaganda techniques and argues that Daesh’s media refrains from publishing some visual recordings for a long time so that they always have new material in their archive in times of resource scarcity (Al-Iraqi 2019, 9). Moreover, Daesh has controlled and influenced the minds, hearts, and behaviors of its target audiences, and stabilized its power using different techniques, such as: appeal to authority; appeal to fear; black-and-white fallacy; labelling and demonizing the enemy; faulty analogy; exaggeration; cherry-picking; and control of information.

Polarization Policy in Media

Polarization is a significant part of Daesh’s communication strategy. Daesh has highlighted the dichotomy between itself and its enemies in its media. Daesh has claimed the authority to speak, not only on behalf of all people under its control, but also on behalf of the entire Muslim world, using ‘we’. It also directly and indirectly, addresses ‘others’ uniformly as ‘they’. As Al-Derzi notes: “Daesh … depends on dividing the world into two parts: The Islamic World and the Kufr World” (PI 2017). Similarly, Ghanem Yazbeck (PI 2017) insists that “IS (and all Salafist-Jihadists) built their base, their conception of life and the world on a Manichean view…and this is why it is attractive to people.” This attitude has been reflected in Daesh’s media.

Daesh’s media are filled with claims and arguments that have a positive representation of the in-group and a negative representation of the out-group. They present the ‘self’ as Dar al-Islam in that the rule of Islam is dominant, and negatively portray enemies and opponents as Dar Al-Kufr, responsible for Sunni Muslims’ marginalization and humiliation. It has depicted the oppression that Muslims are subjected to everywhere, painted a victimized image of them and drawn the attractions of the Khilafah, where they only can provide the Muslims' rights, respect, and dignity. Daesh's media represent the Islamic State as the only defender and supporter of Sunni Muslims, which is a sign of in-group identity.

Daesh has tried to humiliate others in its media, and show itself as a powerful actor by producing videos or publishing images of kangaroo courts, uncommon violence and unusual killings, foreign-hostage executions, immolation and drowning of local citizens to frighten its opponents and enemies. Other aspects of polarization in Daesh's propaganda entail downgrading its enemies’ power, exaggerating its military successes in the battleground or operations in different countries, and downplaying or ignoring territorial and leadership losses in its various media, reframing its military defeats as tests from Allah, and convincing its audiences that Daesh continues to remain and expand its power.

Utilizing the Latest Technologies

Daesh has been flexible and up to date with technology and recent advancements. Its productions are very professional, high resolution, and high quality by any standards (Al-Tukmehchi, PI 2017; El.Meshoh, PI 2017; Ontikov, PI 2017). Besides benefiting from decades of cumulative media experiences in the world of Salafi-Takfiri groups, it has utilized a powerful media team and the latest technologies in producing videos, images, nasheeds, newsletters, and magazines to release its propaganda.

Daesh has been able to employ modern media tools of photography and cinematography and artistic direction to spread its messages, influence its audiences, and the international general public. According to Saleh (PI 2017), “Daesh ideologically was not as strong as Al-Qaeda's in the region, and therefore it had to rely on modern technological methods to attract fighters.” Similarly, Nayouf (PI 2017) claims that “their propagandists are highly trained staff, really digital natives of digital-age children, social networks... They know more about the functioning of the Internet and video games than about the Quran.” Moreover, Al-Hashimi (PI 2017) highlights the participation of foreign members who have technical and theoretical media expertise, which can be utilised to serve the organization and provide high technical media support. He explains:

Daesh has used CGI (computer-generated imagery) for some of its films, such as ‘Healing of the Believer’s Chest’, and AVID technology for editing various videos, such as ‘Flames of War’, which are both very expensive and complicated, and require professional producers and editors (Al-Hashimi, PI 2017).

Thus, Daesh has benefited from expert teams, professional media personnel, and sophisticated tools (for example, advanced cameras, sliders, cranes, green screens) to spread its messages among audiences.

Maintaining a Powerful Online Presence

Daesh has tried to show its ubiquitous and powerful propaganda on different online platforms. As “Daesh considers the social media [sic] to be a means of jihad for the sake of God, and as key elements of its success, as well as to support its strength,” (Rafiqi, PI 2017) it has invested in this domain considerably.

Despite the daily suspensions of thousands of its accounts in different online platforms and the removal of its texts, Daesh has tried to maintain its online presence by creating new accounts, reposting the deleted productions, finding new platforms for disseminating its texts, and alerting others to the new addresses. Besides, it started using Telegram, Hoop, Tam Tam, and many other social platforms after the suspension of its accounts on Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and Facebook. Although Telegram has blocked many Daesh-related channels, they have always quickly returned, and Telegram is still Daesh’s main platform.

Furthermore, while most of Daesh’s accounts were suspended on various platforms, through following a Whack-A-Mole game, dozens of new accounts or platforms were created and used daily. Al-Tukmachi (PI 2017) explains that Daesh uses these platforms to “escape international intelligence surveillance and to give the impression that it is widely backed and supported by public opinion by creating thousands of fake profiles on social media websites.” Moreover, J. Magnier (PI 2017) argues that by offering thousands of backup accounts to replace those suspended by Twitter and Facebook, Daesh wants “to make sure the entire world has access to the information distributed and manipulated by its war media ministry,” and “to make sure it was killing a large number of people with a very large audience watching, to gather recruits, inflict fear into the heart of its enemies and watchers, and give a disproportionate image of its power,” (Ibid.).

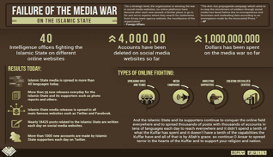

Based on the “Failure of the Media War On The Islamic State” infographic, which was released by Yaqeen Media’s Telegram channel in May 2017, Daesh has considered itself a winner in the media war that has conquered the online field everywhere. This infographic indicates that Daesh's media contents have been shared in more than 40 languages. While the number and quality of the media content deteriorated after Daesh's defeats in Syria and Iraq, and the consequent loss of most of its territories, many fighters, media strategists, and media men, it is still producing different types of content regularly.

Figure 11. Failure of the media war against Daesh (Yaqeen, 2017)

Another part of Daesh’s digital media strategy is hijacking hashtags, exploiting unrelated trending issues, and using the reputation of others. By using hashtag hijacking during global events, and the accompanying popular hashtags, Daesh has attracted and increased its potential audiences, like what it did during the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil. Daesh used a photo of a decapitated head and the caption “This is our football, it’s made of skin #WorldCup” to spread its message (Singer and Brooking 2015). Daesh has also used some special hashtags, such as #WeareallISIS (Stern and Berger 2015) in order to draw more attention on social media. Moreover, through using ‘The Dawn of Glad Tidings’, which is an Arabic-language app, Daesh tried to share and spread its messages to a broader user base.

Furthermore, besides publishing content for its supporters, it also works to understand the needs of this audience by frequently asking for surveys to be completed and pays attention to the reactions and comments they get (Al-Hashimi, PI 2017). Therefore, it can be seen that Daesh’s supporters fight tooth and nail against any restrictions placed on them having an online presence.

Sending Contradictory Messages

Viewing Daesh’s communication strategy only in terms of the professionalism of its media would lead to an incomplete picture. Therefore, studying the different contradictory aspects of Daesh's media content in the reviving, surviving, and expanding of its power should also be taken into account.

The subjects of Daesh’s media content are diverse, and these productions are not just on the topic of violence. The messages are tailored based on their target audience, therefore they are sometimes contradictory. According to Al-Hashimi (PI 2017), Daesh’s texts “combine opposite messages and methods that affect intellectual individuals as well as those who are ignorant.” Similarly, Hashem (PI 2017) suggests:

They tend to terrorize their enemies before even reaching them by posting pictures and videos of their brutality... It also aims to show its human face by producing footage of friendly IS members distributing aid to people in need in areas within the state’s proclaimed borders.

Figure 12. A care home for the elderly in Wilāyat Ninawa

Daesh has intentionally tried to display its atrocities and gruesome face next to compassionate features in its propaganda. However, violence and the murder of civilians were not Daesh’s main aims. Rather, these activities have been used in order to propagate their messages to a larger audience through the shock factor. According to Winter:

The brutality of some of its propaganda eclipses the complexity of most of its propaganda… but it has a lot more to offer than that, and the reason that people from around the world that have joined [...] is because it is promising them something they aspire to... (PI 2017)

While violence, hate, revenge, kindness, victimhood, utopian life, welfare, social services, and selective Islamic ideas are among the major contradictory themes and subjects seen in Daesh’s propaganda, portraying a normal situation and a utopian life inside its territories is an important tactic used in Daesh's propaganda. Through producing a variety of content, such as displaying meals, distributing images of its aids (zakat) among poor people, and releasing news about the opening of children’s hospitals, Daesh tried to highlight another face of the Khilafah, showing ordinary life inside its territories, displaying markets overflowing with food and clothing or workers repairing roads, and rejecting the propaganda against itself.

Daesh displayed itself as a fully functioning state that cares, supports, and defends its people. For example, to challenge the dominant discourse of its enemies about terror and terrorism, in the Al-Kufr is One Religion 1 (2014) video, released by the Wilāyat al-Khayr Media Office, when the audiences see a civilian’s home had been demolished, with the man stuck under the wreckage and his sheep killed by an airstrike, the narrator asks: ‘Where are the terrorists? Are these sheep terrorists? Or is this civilian a terrorist? [...] See what they do with Muslims? With their livelihoods, with their wealth [...] kill all Muslims...’ (2014). In the second part of Al-Kufr is One Religion 2 (2015), this message was repeated: ‘[…] they attack us. They attack our people. We did not attack them. They send fire on us. We did not burn them. All worlds denounce IS for Moaz al Kasase (a Jordanian pilot) burning, but no one denounced them for burning us, our homes, our youth…’ to neutralize enemies’ propaganda and justify its own violence.

Targeting Various Audience Groups

The audiences of Daesh's propaganda, as Smith (2019) notes, can be classified into: “(1) those who are initially predisposed to react as the propagandist wishes, (2) those who are neutral or indifferent, and (3) those who are in opposition or perhaps even hostile.” Propaganda can be more effective with different coercive, cultural, or economic actions to convince people, and Daesh has used all these methods to attract more Sunni audiences. As Chulov (2014, b) explained, “some Sunnis joining out of coercion, others from fear and a smaller number from a conviction that the jihadis share their values and are acting out pre-ordained prophecies,” and Daesh’s propaganda played an important role in cultivating this perception.

Among the methods Daesh has used to attract more audiences there are active interactions and close relationships with their supporters. Bouzar (PI 2017) claims: “While AQ relied on a theological plan to gain support, Daesh relies on intimate ties with the youths.” Similarly, Al-Hashimi (PI 2017) argues that Daesh's media discourse depends on interacting with the public. Moreover, Fallahpour (PI 2017) emphasises the importance of holding a dialogue as opposed to a monologue, to create a friendly atmosphere for increased influence. This strategy has helped Daesh find more supporters all around the world.

Daesh’s media has targeted audiences of different ages, genders, ethnicities, and nationalities, and has produced various kinds of productions for every taste. Whereas its offline media has targeted audiences inside its territories, its online media has been aimed at different audiences outside its territories, including both its supporters and enemies.

Furthermore, Daesh's media emotionally manipulates women in order to attract them from different countries to join its ranks. Ontikov (PI 2017) claims:

As for my country, Russian society was absolutely shocked when the MSU student from a rich family Varvara Karaulova had left her home in 2015 to join Daesh. She has fallen in love with a terrorist in Syria. And by the way, she was writing to him via social media.

Accordingly, Daesh’s propaganda audience is diverse and includes enemy politicians, mainstream media, ordinary people, members of Daesh, and supporters.

Providing Online and Offline Texts

Daesh's propaganda has included online and offline texts. Besides the online publishing of various materials, Daesh has released offline texts and distributed them in various places. Therefore, the role of offline media inside Daesh’s territories is quite important, and offline methods of communication should also be considered in addition to online media in studying Daesh’s propaganda.

Figure 13. Releasing a video in a mosque in Furat

In addition to Al-Himmah publication, which has produced many print books and brochures along with its online texts, Al-Bayan Radio and Al-Naba newsletter are also among Daesh’s notable offline media for local audiences. Daesh distributed its videos, newsletters, and magazines in various media points, mosques, and schools. As J. Magnier (PI 2017) argues, “Daesh did everything to brainwash its supporters and those living under its control, to keep these informed and fed with ‘cherry-picked’ information.” He also explains: “The discipline and the effective use of Daesh’s media, online and offline were at a high level.” (J.Magnier, PI 2017)

Figure 14. Distribution of print newsletter inside Wilāyat al-Furāt

However, due to lack of access to direct information from the inside, it is impossible to obtain precise statistics regarding print media circulation. It is also difficult to determine the number of Daesh’s accounts across different platforms, websites, and blogs as they are always subject to suspension.

While the target audiences of Daesh’s offline and online media are different, their messages follow the same goal, which is to portray Daesh as a powerful and victorious actor, and also to present its enemies as weak and defeated players.

Strengthening Counter-Surveillance Activities

While using diverse online media to disseminate its different messages to target audiences outside the Khilafah, Daesh has limited its soldiers and people’s access to the Internet, and social and mobile media inside its territories, and used various counter-surveillance technologies similar to its enemies’ tools to counter and neutralise their propaganda. As Mohammed Ali (PI 2017) states:

Due to Daesh’s deep understanding of the importance of social media, after it had controlled Mosul, Daesh sought to prevent the population from using the internet and social media, and thus to only be subjected to the content published by Daesh and its channels, and it punished those who violated these orders.

Daesh has also considered the cell phone as an enemy of its soldiers. Therefore, the work of mobile network communication towers was often disrupted by Diwan Amn al-Aam (Public Security Ministry), in order to protect the security of the soldiers against spyware (Al-Nabā 55 2016, 14). Daesh believes that these cell networks are managed by foes (apostates), and preventing their spies from contacting their masters has been part of the plan (Al-Nabā 55 2016, 14). It has also warned about using mobile phones in the headquarters (Al-Nabā 56 2016, 8). In this regard, J. Magnier (PI 2017) claims: “Daesh has an ‘online Social Media Hisba (police)’ to monitor what is shared by its militants or those living under its ‘state’, and those who could be potential spies or intruders.”

In addition, Daesh knows that the enemies’ security and Intelligence services allocate a large part of their capacity and resources to follow their soldiers and collect information on IS (Al-Nabā 55 2016,14). Due to this danger, Daesh members are not allowed access to the Internet and use of social media platforms were prohibited. For example, according to Shabaan (PI, 2017) “in Sinai, neither soldiers nor ordinary people have access to the Internet and social media.”

Figure 15. Delegated Committee bans fighters from using social media

Therefore, Daesh's online activity is paradoxical. On the one hand, it considers the Internet, mobile, and social media as the domain of Kuffar, and so it has limited its soldiers and people’s access to the Internet. On the other hand, it has used various counter-surveillance technologies to neutralise possible espionage operations. Moreover, it has benefited from online media and technologies to disseminate its messages to external audiences.

Circulating Simple and Repeating Messages

To maximize effectiveness, Daesh has created comprehensive propaganda, with endless reach. Daesh wants to be viewed and heard in as many places as possible. Repetition (and emphasis on certain messages) is an important strategy and the essence of Daesh’s propaganda.

Consistent with Gramsci’s emphasis upon the importance of repetitiveness, particularly when he explains, “repetition is the best didactic means for working on the popular mentality” (Gramsci 1999), Daesh repeated its messages across its various media to convince people of the validity of its messages. Through repeating messages, Daesh’s propagandists attempt to transform the beliefs and values of their audience. In this regard, Paul and Matthews (2016) argue, “repetition leads to familiarity and familiarity leads to acceptance.” Therefore, frequent exposure to short and attractive messages would encourage Daesh’s audiences to accept the messages. Daesh has exposed its audiences to the same messages in different formats (such as audios, videos, and written texts) as frequently as possible across numerous off and online media. In line with Rafiqie (PI 2017), who emphasises “the simplicity of speech” and “plays on passion” as two of the main elements of Daesh’s power, Daesh follows the idea that messages are more effective when they are simple, attractive, and repeated. For example, ‘Remaining and Expanding’ is the main creed of Daesh since its establishment and is a significant part of its propaganda. Through repetition of this simple message and memorable slogan in different media, and across diverse genres, Daesh has tried to reinforce its ideas and alternative views. Repetition is part of Daesh’s propaganda in order to stress the importance of the point, and to make messages seem more plausible.

Conclusion

Daesh has been regarded as a powerful actor in the international arena since its inception. The primary aim of this study was showing the role of Daesh’s media (2014-2017) and messages in this regard.

For Daesh, Jihad in the media is considered to be as important as Jihad in the real world in order to remain and expand. It has had different uses of media. These include conducting psychological warfare, training, fundraising, propagandizing, communicating, recruiting, networking, and planning and coordinating terrorist acts. Therefore, the media have played a fundamental role in Daesh's daily activities, and have mainly been about control, influence, communication, and visibility.

Daesh has relied on different kinds of media — especially various types of digital media platforms — to broadcast its propaganda messages to supporters and adversaries, both in and outside its territories. However, Daesh is not the first radical group that has used (digital) media to attain its purposes. In recent decades, all of the main radical, extremist, and terrorist groups have used the new (online) technologies of their era and have benefitted from various platforms to different extents. Since the 1990s, the Internet has been an ideal place for them and has helped them communicate, train, terrorize, and expand their frightening messages among audiences.

This study examined Daesh’s media power and sought to understand how and by which means and methods Daesh’s diverse media have worked and its messages have been released inside and outside the Khilafah in recent years. This paper scrutinized Daesh’s media power, including its official media and strategy to understand the role of its propaganda in a psychological war alongside its other activities. This was done to discover how Daesh communicates its ideology and produces content for its target audiences inside and outside the Khilafah. Studying its various media organizations, such as Al-Furqan, Al-Hayat, Al-Itisam, Ajnad, Al-Bayan, Al- Himmah, Amaq, Nashir, and Wilayat media offices has helped to know the ways and methods that Daesh has used media to distribute its propaganda and messages.

This research demonstrated that Daesh’s media activity has been a significant weapon against its enemies, and has acted as a continuation of its military actions to weaponize the Internet, terrorize people, and announce that they are more powerful than an atomic bomb. Furthermore, it showed Daesh’s polarization policy in the media via the highlighting of the dichotomy between “itself”, as the only supporter of Sunni Muslims, and “Others”, as those responsible for Sunni Muslims’ marginalization and humiliation.

Moreover, utilizing the latest technologies, such as expensive, complicated and professional tools for photography, and cinematography were other parts of Daesh’s media strategy. This strategy also included maintaining a powerful online presence, via creating new accounts to replace those suspended, to repost the deleted content, to find new platforms, to escape international intelligence surveillance, and to hijack hashtags to make sure the entire world has access to its content.

In addition, sending contradictory messages to reach diverse aims, such as to terrorize its enemies through coercive actions from one side and to create consent among its people via showing its human face, on the other; targeting various audiences to attract more people to its messages, both in- and outside its Khilafah; providing online and offline content/media for various areas, such as battlegrounds; strengthening counter surveillance activities in order to protect the security of its territories and the safety of its soldiers, to harden the work of its spies, and to neutralize its enemies' activities; and an effective propaganda system through which to create consent, transfer its ideology to the greater target audiences, and to prevent people from critical thinking have been other main Daesh’s media strategies.

The rapid growth of Daesh since 2014 has triggered much discussion about the reasons behind its fast rise and its attraction, and especially about the role of (digital) media and the Internet in its increased strength. The researcher believes that while Daesh's media matters, it has not been the causal factor behind its growth and other political, social, cultural, and economic issues should be taken into account next to its media activities. Lastly, while Daesh has put a high priority on different kinds of media to disseminate its messages, it should be noted that different mainstream media have also greatly helped it in the distribution of its content.

References

“Ahamm al-Marahil fi Masirat tatweer Nashrat al-Naba” (The most important steps in the process of publication of Al-Naba), Al-Nabā’ 1, Central Media Diwan, Oct 17, 2015, 2.

Al-Adnani, Abu Muhammad. “Ghol ‘Moutou bi Gayzekom’!” (Say, ‘Die in Your Rage!’). Al-Furqan Media, 26 Jan 2015a.

Al-Adnani, Abu Muhammad. “Fa Yaghtolun wa Yoghtalun” (So they kill and are killed). Al-Furqan Media, 12 March 2015b.

Al-Baghdadi, Abu Bakr. “Khuṭbah and Jum’ah Prayer in the Grand Mosque of Mūṣul (Mosul)” (Friday Sermon in Mosul, Iraq). Al-Furqan Media, July 4, 2014

“Al-Hatif al-Jawwal ... al-Ma'asiyat al-Musta'siyah” (Mobile phone ... intractable disobedience), Al-Nabā 56, Central Media Diwan, November 24, 2016, 8-9.

“Al-Hatif fi Khidmatik wa fi Khidmat A'ada'ek” (The phone is at your service, in your enemies’ service as well!), Al-Nabā 55, Central Media Diwan, November 17, 2016, 14-15.

Al-Iraqi, Abu Muslim, "Shahadah Amni Tayib” (Testimony of a repenting amni), Mu'assasat al-Wafa'al-Ilamiya, 2019, in: Opposition to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: The Testimony of a Former Amni, translation by Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad, May 21, 2019, http://www.aymennjawad.org/22715/opposition-to-abu-bakr-al-baghdadi-the-testimony. Accessed Aug 19, 2019.

Al-Iraqi, Abi Muslim, "Shahadah Amni Tayib" (The Testimony of a Repenting Amni (II)), Mu'assasat al-Wafa' al-'Ilamiya, July 2019, in: Opposition to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: The Testimony of a Former Amni (II), translation by Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad, September 29, 2019, https://www.aymennjawad.org/23303/opposition-to-abu-bakr-al-baghdadi-the-testimony. Accessed: Oct 2, 2019.

Al-Iraqi Mustafa, Difference Between Amaq and Nashir, CALIPHATE_MEDIA Telegram Channel, 2017.

“Al-Itisaam Media”, Justpaste.it, December 9, 2014. https://justpaste.it/pzd_content20141209. Accessed: May 25, 2018.

“Al-Kufr Millah Wahidah (1)” (Al-Kufr Is One Religion (1)). Wilayat al-Khayr, October 27, 2014.

“Al-Kufr Millah Wahidah (2)” (Al-Kufr Is One Religion (2)). Wilayat al-Khayr, February 14, 2015.

Al-Masri, Abu Abdullah. “Islamic State Caliphate on The Prophetic Methodology, in: The Isis Papers: A Masterplan For Consolidating Power”. The Guardian, December 7, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/07/islamic-state-document-masterplan-for-power. Accessed: January 12, 2017.

Al-Muhajir, Abi-Abdullah, Masa’il fi Fiqh al-Jihad (Issues in the Jurisprudence of Jihad). Islamic State: Al-Himmah Publication 2015.

Al Quraishi, Abu Hamza. “Faqsus Al-Qasas La'allahum Yatafakkarun” (So narrate to them stories of the past, so perhaps they will reflect) Al-Furqan Media October18, 2020.

“Awham al-salibiyyin fi Asr al-Khilafah” (The Illusions of the Crusaders in the Age of Khilafah). Al-Nabā 34, Central Media Diwan, June 7, 2016, 3.

“E'elan an Nashr Mussisat Al-I’tisam. Al-tabi'ah li al-Dawlat Al_iraq Al_islamiyah- Asdaratha ebr al-Jibhat Al-e'elamiyyah al-Islamiyyah al-Alamiyyah” (Announcement on the publishing of al-I'tisam media Foundation- A Subsidary of the Islamic State of Iraq- It will be Released Via GIMF) Jihadology. Feb, 21, 2013. https://jihadology.net/2013/03/08/new-statement-from-the-global-islamic-media-front-announcement-on-the-publishing-of-al-iti%E1%B9%A3am-media-foundation-a-subsidiary-of-the-islamic-state-of-iraq-it-will-be-released-via-gimf/. Accessed: July 23, 2017.

Chulov, Martin. “What Next for Islamic State, The Would-be Caliphate?” The Guardian, Sep 3, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/03/islamic-state-caliphate-what-next. Accessed Sep 3, 2019.

“Dawlat al-Islam Qamat” (My Ummah, Dawn Has Appeared). Ajnad Media Foundation, December 4, 2013.

“Dawlati la Tuqhar” (My State Will Not Be Vanquished). Ajnad Media Foundation, November 18, 2017.

“Dawlati Baqiya” (My State Remains). Ajnad Media Foundation, June 7, 2017.

“Flames of war1”, Al-Hayat Media Centre September 19, 2014.

“Flames of War II”, Al-Hayat Media Centre November 29, 2017.

“For The Sake of Allah”, Al-Ḥayāt Media Centre, September 6, 2015.

“Ghamat Al-Dawalah” (Rise of the State). Ajnad Media Foundation, January 16, 2016.

“Ghariban Ghariba” (Soon... Soon), Ajnad Media Foundation, February 4, 2015.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections From The Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. In Qu. Hoare (Trans) & G.N. Smith (Eds.). London: ElecBook, 1999.

Gramsci, Antonio. Letters From Prison. Selected, translated from the Italian, and introduced by Lynne Lawner. Translated from Lettere dal carcere. New York: Harper & Row, 1973.

Ibn Abdul-Wahhab, Muhammad. Al-Osul al-Salasah wa al-osul al-Sittah wa al-Qawaed al-Arba'ah (The Three Fundamentals, the Six Principles, the Four Basics). Islamic State: Al-Himmah Publication, 2017.

Ingram, Haroro J. “What Analysis of The Islamic State’s Messaging Keeps Missing”, The Washington Post. October 14, 2015.

“Inside the khilafah” 1-8, Al-Hayat Media Center 2017.

“Jayl al-Khilafah” (Generation of the Caliphate). Wilāyat al-Khayr, September 6, 2016.

Kadivar, Jamileh. Exploring Takfir, Its Origins and Contemporary Use: The Case of Takfiri Approach in Daesh’s Media, Contemporary Review of the Middle East 7(3) 2020a. DOI:10.1177/2347798920921706 .

Kadivar, Jamileh. Ideology Matters: Cultural Power in The Case of Daesh, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, (2020b) DOI: 10.1080/13530194.2020.1847039.

KhilafaTimes, https://khilafatimes.wordpress.com/about/. Accessed: Aug 28, 2017.

“Kasr al-Hudud” (Breaking Of the Border). 2014. Al-I’tiṣām Media, June 29, 2014.

Majmou Rasa'il wa Moallafat Maktab Al-Buhuth wa Al-Dirasat (Collection of the writings of Office of Research and Studies). 6-volumes. Islamic State: Maktab Al-Buhuth wa Al Dirasat., 2017.

“Message of the Mujahid”/1-5. Al-I’tiṣām Media, 2014.

“Mosul, Rawayat Al-Ukhra” (Mosul, Another perspective) Sarh Al-Khilafah, Nov 29, 2020.

“Mujahid Anta Ayyuhal A'alami” (Media Man, You Are a Mujā hid Too). Wilāyat Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn media office, 2015a.

Mujahid Anta Ayyuhal A'alami (Media Man, You Are a Mujāhid Too). Al-Himmah Publication, 2015b.

“Nawafidh ala al-Ard Al-malahim” (A Window Upon the Land of Epic Battles)1-44, Al-I’tiṣām Media. 2013; 2014.

"Nazif Al-Hamalat" (Bleeding campaign) Wilayat Sinai, Jan 8, 2021.

New statement from the Global Islamic Media Front: “Announcement on the Publishing of al-I’tiṣām Media Foundation – A Subsidiary of the Islamic State of Iraq – It Will Be Released Via GIMF”, 2013. Jihadology, March 8, 2013. https://jihadology.net/2013/03/08/new-statement-from-theglobal-islamic-media-front-announcement-on-the-publishing-of-al-iti%E1%B9%A3am-mediafoundation-a-subsidiary-of-the-islamic-state-of-iraq-it-will-be-released-via-gimf/. Accessed: May 23, 2018.

“Nuqat al-A’alamiyyah: al-Nafidha ad-Dakhiliyyah li-A’alam ad-Dowlat al-Islamiyyah” (Media Points: The inner window of The Islamic state's Media). 2016. Al-Naba 21, Central Media Diwan, March 8, 2016, 12-13.

Paul, Christopher and Miriam Matthews. “The Russian Firehouse of Falsehood Propaganda Model,” Perspective: RAND Corporation. 2016. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE198.html Accessed: July 4, 2020.

“Rayat Al-Tawhid” (The Banner of Tawheed) Ajnad Media Foundation, Jan 2018.

“Salil al-Sawarem” (Clanking of the Swords). Ajnad Media Foundation, September 25, 2014.

“Shariat Rabbana Nouran” (The Shari’a of Our Lord is a light). Ajnad Media Foundation, November 22, 2014.

Sawt Al-Hind (voice of Hind) 13, Feb 22, 2021.

Singer, Peter Warren and Emerson Brooking. “Terror On Twitter: How ISIS is Taking War to Social Media—and Social Media Is Fighting Back”. Popular science, December 11, 2015.

Smith, Bruce Lannes. “Propaganda”, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/propaganda. Accessed: September 4, 2019.

Stern, Jessica, and J. M. Berger. 2015. ISIS: the state of terror. New York, N.Y.: Ecco Press, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

“The End of Sykes Picot,” Al-Hayat Media Center June 29, 2014.

The Islamic State Delegated Committee. “Silsilat al-Ilmiyyah fi Bayan Masai’l al-Minhajiyyah 1-6” (Scientific series in the statement of methodological). Al-Bayan Radio. Sep 2017.

“The Rise of the Khilafah And the Return of the Gold Dinar”, Al-Hayat Media Centre 2015.

“The Structure of the Khilafah”. Al-Furqan Media, July 6, 2016.

“Ummato Walud” (The fertile nation) 1-5. Wilayat al-Raqqa, 2017.

Weiss, Michael and Hassan Hassan. ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror. New York: Regan Arts, 2015.

Winkler, Carol K., Kareem El Damanhoury, Aaron Dicker, and Anthony F. Lemieux. “The Medium is errorism: Transformation of The About to Die Trope in Dabiq”. Terrorism and Political Violence, (2016): 1–20. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09546553.2016.1211526?needAccess=true. Accessed Aug 2, 2018.

[1] Due to the limitations of space, this paper only focuses on Daesh’s media organizations and its media strategy.

[2] The interviewees included: Abdel Moniem El-Meshoh (A Saudi Arabian researcher in cyber-terrorism, Chairman of the Sakinah campaign; Ahmad Al-Derzi (A Syrian Physician, writer, and analyst); Andrey Ontikov (A Russian Political analyst in Middle East Affairs, Journalist at the Russian Izvestia newspaper); Ali Hashem (A Lebanese Journalist, AlMonitor and BBC Columnist); Ali Ornek (A Turkish journalist who works as Editor and Chief-editor in the daily Sol and the daily Hürriyet); Charlie Winter (A British researcher, studies terrorism, insurgency, and innovation, author of several papers about Daesh and its activities on social media); Dalia Ghanem Yazbeck (An Algerian researcher, analyst, writing about Radicalisation, Jihadism, and Daesh); Dounia Bouzar (French Director of the Centre for the Prevention of Islamic Sectoral Derivatives (CPDSI), writer of numerous books and articles about Jihadi thought); Elijah J.Magnier (A Lebanese senior Political Risk Analyst, veteran war correspondent, political and terrorism/counterterrorism analyst, Al-Rai Chief International); Hisham Al-Hashimi (A military strategist, historian, writer and researcher in extremism, and terrorism affairs); Mohamed Abdelouahab Al-Rafiqi (A former Salafi cleric and preacher from Morocco, the Chairman of the Almizane Centre for De-radicalisation and Prevention of Extremism); Mohammad Ramadan (An Egyptian religious scholar in Al-Azhar Al-Sharif, writing about Islamic thought); Mahmoud Shabaan (An Egyptian Journalist, working at Alhiwar TV, specialised in Islamic movements); Najah Mohammed Ali (An Iraqi Journalist, a columnist for Al-Quds Al-Arabi, writer of many articles about extremist groups); Roland Bartetzko (A German soldier who volunteered for the Bosnian-Croat side (the HVO) in the Bosnian War (1992–95) and the ethnic Albanian rebels (the KLA) in the Kosovo War (1998–99), a lawyer and writer); Salah Al-Tukmehchi (Director of the Iraqi Observatory Network, publisher, writer, and journalist); Saleh Nayouf (A Syrian writer, academic and researcher, writing about ideological and political thought and Islamic groups); Siavash Fallahpour (An Iranian writer and Journalist covering ME and Arab Affairs); Somer Saleh (A Syrian researcher and writer, writing about the Middle East and Daesh).

[3] Takfir is about labeling other Muslims as kafir (non-believer) and infidels, and legitimizing violation against them (Kadivar 2020a). Takfiri groups are groups that follow this approach and excommunicate other Muslims.

[4] The term ‘Nasheed’, as used by Daesh, signifies a special kind of song, mainly sung without instruments, and considered as Halal (licit) poetry. Nasheeds are mostly about religious subjects, such as Islamic beliefs, God and his Messenger.

[5] An official statement from an Islamic leader

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub