Issue 23, winter/spring 2017

https://doi.org/10.70090/YD17PPFV

During a lecture entitled “‘I Think We Will be Calm During the Next War’: Past, Present, and Future Violence in Lebanese Comics,” Ghenwa Hayek, assistant professor of Modern Arabic Literature at the University of Chicago, discussed Lebanese comics as a means of reflecting war and conflict. After her presentation she spoke with Middle East Studies graduate student and Arab Media & Society contributor Yishu Deng about the evolution of the art form and how the 2006 war in Lebanon initiated an outpouring of comics addressing war in the country.

Hayek is the author of Beirut, Imagining the City: Space and Place in Lebanese Literature (I.B.Tauris, 2014). An excerpt from her chapter “Beirut: Past, Present, Future? Memory and Anxiety in Contemporary Lebanese Comics” is available here.

Arab Media & Society: What sparked your interest in Lebanese comics? How did you start working on this topic, this genre specifically?

Ghenwa Hayek: I became interested in Lebanese comics in 2006 when I returned to Beirut to do dissertation work, war broke out and part of my project was trying to understand the different ways that Beirut had been represented in fiction across different moments of it’s history. I was particularly interested in trying to relate crisis with shifts in formal representation or modes of representation. Comics sort of became of the final chapter of this narrative, because for me it represented another shift in the long line of narratives about the relationship between Beirut and it’s people, and how different artists thought and imagined the city of Beirut.

AMS: To your mind, how was this long line of narratives formed? Did this expression through comics evolve from something else?

GH: I think it’s important to point out that I don’t think that this narrative is necessarily organic or even tells a complete story. What I was interested in—or the way I organized it in my book—is that I looked at prewar novels then traced the transformation of the Lebanese novel over the war years and post war period beginning in 1990. Finally, I got to the comic as a sort of a development of some of the ideas from these novels. So for example, how did historical novels written in the early 2000s imagine Beirut? How did they try to reconcile personal identity with the history of the urban space and the history of the changing city? For me, comics were the last in line in terms of genre and form, but definitely not the only, and definitely not the next natural evolutionary step.

AMS: You mentioned in your presentation that there has been an outburst of comics in the 21st century, in your view, what are the reasons behind this new popularity?

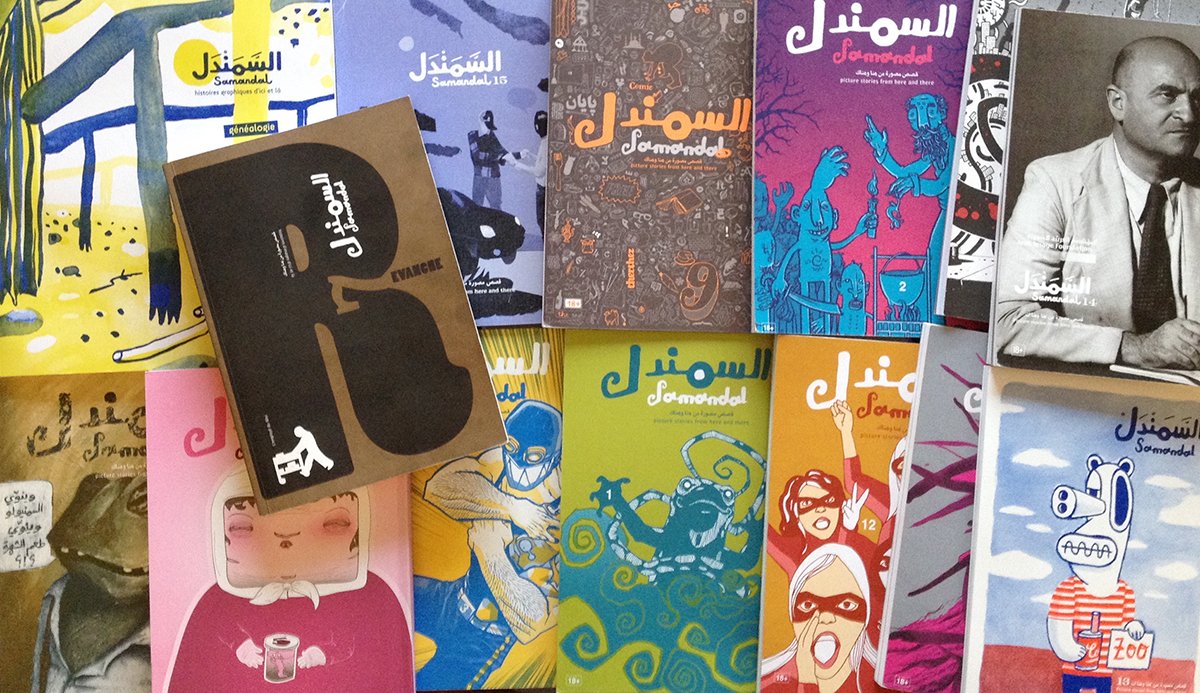

GH: I think part of it is a generation of people who grew up reading bande dessinée and comics, English comics, and Arabic translations of American comics: A generation who grew up on cartoons. The people who grew up with this visual language and identity coming of age and having this medium to express themselves. The two authors that I talk about in the book, Lena Merhej and Mazen Kerbaj but also the Samandal collective and others, they are all around the same age, so I think that there is a generational phenomenon that happened at this particular moment in time.

AMS: What do you think is the media’s role in this? And how has media been reporting on and covering Lebanese comics?

GH: I think that there has been a considerable amount of coverage of Samandal for example in the Lebanese media. For last year, when Samandal was sued by the government for indecency, that issue made a big slash in the international media. There was a piece written about them in the New Yorker and the New York Times. During the moment in which these novels texts were coming out, I think there was coverage in the Lebanese press, but it was nothing as dramatic and nothing as internationally impactful as when they hit their legal hurdles last year.

AMS: Who is the major audience of these comics? As international coverage has grown, has the audience become more international?

GH: Well Samandal, which both Lena Merhej and Mazen Kerbaj contribute to and Lena Merhej is an editor of, was never meant to be a purely Lebanese thing and from the beginning there were calls for contributions from across the world. They had contributors from many different countries, from the US, from the United Kingdom, from Brazil, so I think that the audience has always been international. And when you think about the blog (that I presented on) that was deliberately intended for an international audience. The text that accompanied the images were often in English so that more people could read and understand them. There was very often a direct address to a viewer sitting somewhere in the world to engage with not only the comic but also to actively take bits of the comics and put them in their cities, so I think that from the beginning the audience for that particular kind of comic production has been an international one.

AMS: How did the audience react?

GH: I am not sure, I mean I think that Samandal does very well, I think when they issued a call for help, in order to pay the cost of the fine they had been subjected to by the Lebanese government, there was a pretty good response. I don’t have information about the sales but it is a popular project. They have transitioned to an annual edition rather than issues throughout the year so it now comes out as a big anthology. This is going to be the third year that it does so and its usually around a theme. The first one was around the theme of Genealogy, the second was about the theme of geography, this coming one is around the theme of sexuality, so the comic itself has progressed and evolved from it’s early days in 2008.

AMS: We talked about the international audience and about the language a little bit too. I have noticed that in the comic itself, when it is Arabic, is all colloquial. How does this translate outside of Lebanon?

GH: That’s a very interesting question and I think there are people who do work on comics who are much better equipped to speak to this than I am. I think that there is always a sense with Arabic whenever it’s written in colloquial, there is always a problem of translatability, although Egyptian and Lebanese dialects tend to be understood. I think in the case of Samandal, because translations always come out with the text, it’s audience that doesn’t necessarily get the nuances of colloquial Arabic will always be able to refer to an English or French translation. But it’s always one of the challenges of colloquial Arabic.

AMS: Aside from war and conflict, are there any other topics that are examined in these comics?

GH: In the comics that I looked at for my presentation and for the book, I was really interested in this idea of witnessing war, bearing witness to a state of war. You can see it in issues of Samandal, for example, there were comics that are about everything, about everyday life, there are super hero comics, there are comics about falling in love, and teenagers. The subject matter is quite varied. For example, Lena Merhej’s next project “maraba wa laban,” or “jam and yogurt,” is the biography of her mother. It happens that her mother was raised in Germany during World War II and then part of her adult life was spent in Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War, but it’s not necessarily a war document or testament.

AMS: I think that’s all of my questions. Is there anything else you would like to add to the conversation, something that you want to specifically point out or emphasize?

GH: I think this is a very exciting time for Arabic language comics. I think that Jonathan Guyer is doing some really great things on his blog Oum Cartoon which just has a fantastic name. Last year I went to a fantastic MESA (Middle East Studies Association) panel on comics with several people who have been working on translating comics, mainly from Egypt but not necessarily just from Egypt. This is a really exciting time to be working on and also reading and engaging with this medium.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub