Issue 20, winter 2015

https://doi.org/10.70090/AK15CTPE

If you were sitting in your living room in Egypt four years ago when tens of thousands flooded the streets, unless you were tuned to Al Jazeera, you would have likely had no clue. An uprising ignored by the press is not an error of omission; it is systematic suppression of information by the upper echelons of the Egyptian media. More than four years have passed and it appears little has changed in terms of the type of narrative emerging from Egypt’s national media. In the last 6 months several leaks[1] have emerged, offering further proof of a media in cahoots with the state. To understand this dynamic is to comprehend, at least in part, why Egypt remains in a precarious position.

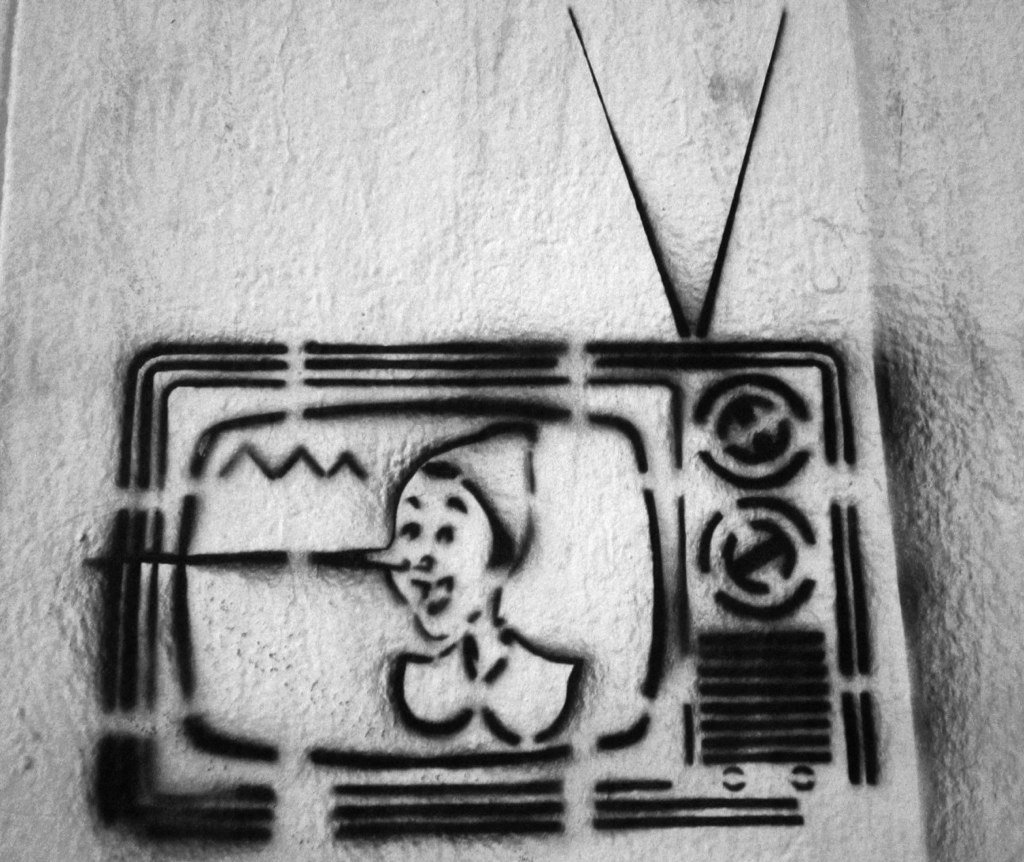

From the first days, state television sought to obstruct Egypt’s volcanic revolution. How this could occur in the age of the Internet, particularly in a nation where penetration rates had exploded by 2014[2], is a testament to the power of an Egyptian media wedded, at the corrupt altar of propaganda, to the Egyptian state. Cameras were turned in the other direction, showing a quiet Nile Corniche as, just hundreds of meters away, demonstrators faced off against police to decide the country’s future, and it did not stop there. In the great tradition of modern Egyptian media, subtlety was lacking. As articulated in a February 2011 piece in Foreign Policy[3], “Egyptian state media began running an insidious propaganda campaign in an apparent effort to terrorize ordinary Egyptians into staying at home and off the streets.”

By the time the revolutionary wheels were turning, and during those crucial eighteen days, the efforts of Egyptian State TV to turn the focus away from a burgeoning movement had delved into the comedic, as channels executed orders clearly emanating from the Mubarak state. If it wasn’t an actor droning on about “drums and different factions, boys and girls, drugs and sexual relations[4]”, it was Egyptian TV manufacturing fake call-ins to denounce the revolution. One such infamous incident involved ‘Tamer’ calling into Egyptian TV (ERTU) to say he had mingled with the men and women of Tahrir and they spoke ‘foreign language very well[5]’. The implication was obvious: Foreign interference in Egyptian affairs, playing on Egyptians’ worst xenophobic tendencies. When the deception was discovered, after coworkers recognized Tamer’s voice as that of a TV employee, it made nary a difference in the approach.

As momentum shifted after Battle of the Camels[6] and February 11th approached, the narrative from both state and private channels suddenly, and in near unison, shifted to a more pro-change tenor. Even as support for the idea of change grew, the notion of deep state-guided narratives remained. And since, the state has largely continued to rely on old tricks.

In the blink of an eye, Mubarak’s reign was terminated by the deafening roar of the millions of Egyptians who took to the streets. President Obama declared, “the word Tahrir means freedom…and forever it will remind us of the Egyptian people and how they changed their country, and in doing so changed the world[7].’’ But in the political realm, not all is what it seems. The counter-revolution was slowly organizing, but before it could do so, a solid media strategy by the interim rulers of the country, the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF), bought time for the offensive to come.

After a historic victory in Tahrir, on March 9th 2011, Egyptians were tortured in the Egyptian museum at its center. Fast-forward seven months to bloodier clashes between revolutionaries and SCAF, and as Egypt’s latest tragedy unfolded across the landscape, SCAF-controlled state media bared its knuckles. The Maspero Massacre should have been an open and shut case, eyewitness accounts in addition to video evidence indicated soldiers killing civilians in full view of the public. But in a starkly unbalanced diatribe, national TV stoked the fires of sectarian division. While Egyptian Christians were being run over by tanks outside the Egyptian TV and radio building (Maspero), Egyptian state television ran the inflammatory subtitle: “Army under attack by Copts[8]”. While Al Arabiya, Al Jazeera and several other local private TV stations, broadcast bloody images of armored personnel carriers running rough shod over unarmed Copt demonstrators, this presenter posited a fabricated reality. “Till now three are dead and twenty injured, all of them army soldiers, by whose hands? By a sect in Egyptian society… there are those firing bullets[9]”. These assertions were patently false, and in one astonishing swoop the victim became the perpetrator. Furthermore, The Guardian documented systematic manufacturing of propaganda, when a former TV employee told the paper that orders would arrive to spin the stories in one direction over another: ‘’I felt like a liar for a long time before I decided to quit[10]’’.

Though the revolution never ruled, the removal of Mubarak forced his camp, the deep state, and the army to make concessions in the short term. In the months that followed January 25, 2011, there was some semblance of media balance. ONTV was home to important pro-revolution presenters. For many months, as the military propagated the idea that the ‘the army and the people are one hand’, ONTV continued to do two things well and consistently: cover clashes with professionalism, and give room for debate about where the nation was headed. Another nascent effort at independent journalism was the privately owned Tahrir channel. Initially led by a host of pro-revolution journalists[11], in the space of a few months a counter-revolutionary partner was brought on board for a cash injection, and the channel shifted its coverage. It would become a telling sign: the insidious influence of pre-Revolution power players had never left the media arena - the dynamic would later have negative reverberations following President Sisi’s election.

But before this, there was Mohamed Morsi and his band of heavy-handed Islamist provocateurs. Chief among TV stations strictly propagating an Islamist vision was the Muslim Brotherhood owned Misr 25, the more popular Al Jazeera (and its Egypt channel Mubashir Masr), and lesser-known Salafist-leaning Al Hafiz and Al Nas. Most of these stations, with the exception of Al Jazeera, did not reach the mainstream. This was partially because they, for all intents and purposes, did not represent classic ‘journalism’. Functionally, these channels were a reflection of the world through an Islamist prism. They saw television, an important purveyor of information in a nation where literacy rates are relatively low by global standards, is an instrument to service the political needs of the ruling regime.

When there was a large gathering in Tahrir to promote Islamic identity the announcer opened by comparing Tahrir to Arafa, a Muslim pilgrimage site, and didn’t flinch when he suggested there were millions present[12]. Months later, during June 30th, it was the Islamist camp that insisted Tahrir could only hold 250,000 demonstrators.

These stations, as with the ruling Islamist cadre, presented a paranoid vision of an Egyptian state where Morsi was constantly hounded. So when Morsi saw it fit before the Ithadiya clashes[13] to usurp pharaoh-like power these channels were silent on the power play and trumpeted any dissidence as pro-ancien regime rhetoric. This media machine took it upon itself to prop up a vulnerable president under attack by enemies, both foreign and domestic. It is little surprise that among the first acts following Morsi’s removal was the closure of these channels[14].

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s arrival as the country’s informal leader on July 3rd 2013, ushered in a new wave of media manipulation, coupled with heightened levels of censorship. Limitations on freedom of speech have been compared to those imposed during Nasser’s time, where voices not representing the state narrative were all but silenced. To say that state owned and private television’s stance in the past 18 months has been largely unbalanced and unprofessional would be an understatement. What has happened is nothing short of a transformation of the television landscape, where multiple channels, while differing in name and number, deliver the same polarizing and reductionist messages. As the Wall Street Journal pointed out, even after the most grizzly massacre in modern Egyptian history, Rabaa in August 2013, left 1000 dead ‘these were deaths the Egyptian channels, by and large, did not report[15]’.

Leaks of activist’s conversations shortly after Morsi’s removal had people suspecting that State Security was directly supplying some presenters with the material. Glaringly, one of the most popular presenters at one private TV station was actually a former State Security officer. In print journalism, one paper stated it would publish a detailed account alleging that General Shafik had won the elections instead of Morsi. Whether true or not, the allegations, if based on sound journalism, should have been exposed to the public but were not. The editor-in-chief was subsequently brought in for hours of questioning by government agents. Despite this, Sisi has maintained that the state is open to all views. And although in rhetoric Sisi still espouses a freedom of speech stance, any pretense by the Egyptian state has been dropped: independent voices, such as Belal Fadl, Reem Magued and Yosri Fouda, have in many cases become persona non grata.

Yet, in an environment of cognitive dissonance many have still chosen to believe this path was acceptable. For the public, one of the many leaks, directly from the head of Sisi’s office, would be the proverbial smoking gun. Sisi’s point man, General Abbass Kamel, was heard telling the former army spokesperson “are you writing?’’[16] as he dictated the pro-government narrative to be relayed to their allies at the private TV channels dominating the airwaves. It is a conversation littered with a sense of entitlement and gross arrogance of the ruling elite vis-a-vis the Egyptian public.

After a particularly brutal October 2014 attack in Sinai left 33 dead, many editors-in-chief didn’t hesitate to gather and effectively declare that they would not pen a negative narrative of the state and the army in the interest of national security. They called it the loyalty pledge.[17] In such an environment, content that deviates from this guarantee are not welcome, and can have severe consequences. The many journalists currently languishing in Egypt’s jails can testify to that reality.

In the heyday of the revolution, there was a bright hope for transformation and freedom. The glare of this hope blinded many to the potential risks ahead. As the picture has grown bleaker, it has become increasingly clear that despite initial headway, the Egyptian media remains controlled by the state. The alternate reality often shown on television screens is a reflection of this.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub