Issue 30, summer/fall 2020

https://doi.org/10.70090/RASG29JM

Abstract

This paper examines the journalism and media education programs in three countries in the Arab region (Libya, Syria, Yemen) that have been or are still in the throes of civil wars and/or polarization along conflicting political ideologies and control of different geographical zones. Based on an online questionnaire distributed among academics affiliated with universities in these three states, results show that the three countries suffer from an extreme lack of proper journalism and media education programs. However, online and blended education can serve as a bridge for these countries to overcome their constraints and challenges, and develop new models for their journalism and media education programs.

Introduction

Scholars and social studies researchers have always been intrigued by how war is covered and packaged to be presented to the world. Audiences often switch between different outlets in search for the voice that supports their side, as well as understand what the ‘other’ is saying. The question of objectivity becomes key, and issues of bias and ethical coverage remain central (Galtung 2003). Most studies in mass communication focus on media performance during times of war or conflict, yet rarely pay attention to journalism and media education during these times (Ziani, Elareshi, Alrashid, and Al-Jaber 2018). This paper surveys the importance of examining media education programs by analyzing the impact of journalism and media programs in three Arab states that have been or are still in the throes of civil wars and/or polarization along conflicting political ideologies and control of different geographical zones in each country, and how journalism and media education is affected partially and/or entirely by these divisions.

Journalism Education in the Arab World

Journalism in the Arab region has origins in ancient Egyptian and Arab manuscripts. The evolution of journalism in the past three decades has transformed how some Arab countries view and deal with news and journalism. Arab journalists have, over the years, learned their practice and skills on the ground upon completing secondary school education. It was with recent technological advancements that more structured university education for aspiring Arab journalists emerged. In 1939, the Egyptian Higher Press Institute was considered the first institution to offer mass-communication courses, later to be rebranded as the Editing, Translating, and Press Institute in the Faculty of Arts at Cairo University. Starting 1954, this institute developed into a more academic unit that offered bachelors, masters, and doctoral degrees in communication and journalism. In 1969, this unit further evolved into the Independent Media Institute, and by 1974, it became the first Faculty of Mass Communication in the Middle East (Abd El Rahman 1988) to teach and offer degrees to professionals. According to Reynolds (2013), the political idiosyncrasies of Arab countries have made it difficult to develop a “culture of journalistic professionalism that is faithful to one liberal model.”

Furthermore, when it comes to Arab media systems, it can be said that Arab governments heavily influence news and information both in terms of content and dissemination. Arab journalists are aware of these conditions and the associated restrictions, and often engage in self-censorship. Despite the views of some that Arab journalists exhibit a lower level of professionalism due to their self-censorship; this does not necessarily mean they are less educated or trained than their Western counterparts. According to Ziani et al. (2018), many Arab journalists are more likely to have received their professional qualification (university or college degree) from Cairo. Unfortunately, more recently there has been an increase in inadequately trained individuals in the field as requirements to practice the profession have been relaxed in many Arab countries, where anyone can become a journalist as long as they abide by the platform’s editorial guidelines (Ziani, Elareshi, Alrashid, and Al-Jaber 2018).

Despite this, but there is also a significant upsurge in the number of university journalism courses and degrees (Frith and Meech 2007). According to Tweissi (2015), there are approximately 135 university media or journalism programs in the Arab world, most of which were established over the last two or three decades. The main challenges facing this field are that academic programs often fall short in practical application and focus more on theory (Tweissi 2015; Allam and Amin 2017). Moreover, most of the university programs tend not to keep up with industry developments. For example, most Arab journalism programs at the university level do not yet offer digital media, media management, or new technologies. This is partially because many Arab countries do not have the means or resources to get their programs accredited. The journalism program at Qatar University, for instance, is one exception that is recognized by many Western universities. These challenges and more result in a poor quality of journalism graduates who later exhibit sub-par skills in the real world. Many Arab universities do not adequately prepare their students for the realities of the journalism industry after graduation. To overcome these difficulties, some Arab higher-education systems send qualified graduates to study journalism abroad to acquire better professional skills.

Journalism Education and War Zones

-

Yemen

The education sector in Yemen in general, and university education in particular, were not immune to the repercussions of the war that has plagued the country since 2014. In addition to the negative consequences of the war, several sectors of society have been impacted by sectarian and divisive content imposed by the Houthi coup militia. This has resulted in frightening amount of politicization and discord within the provinces under the control of the coup authority. Since the Houthis seized control of the capital Sana'a, they have sought by all possible means to impose a contractual guardianship on education and to compel their sectarian ideology into the curriculum. The war that resulted from the Houthi coup against the Republic six years ago has left deep scars on all levels of the education sector.

The war in Yemen, which began as a conflict between the government army and Zaidi[1] militia led by Hussein al-Huthi, began in 2014 in Sa‘ada. In September of that year, Hussein al-Huthi was killed by Yemeni government forces, and the conflict was later led by his father, Imam Badr Addin al-Huthi (Imam Badr al-Huthi has been the Imam of Yemen’s Zaidi sect since 1972 after receiving consensus or bay’a to assume this post).

The brutal war has devastated the country since early 2015. Twenty-one million people (around 75% of the total population) have required humanitarian aid, with 7.3 million being extremely food insecure, and 3.3 million displaced inside the country. Yemen’s health-care system has almost collapsed with around half of health facilities being only partially functioning or destroyed completely, leading to a rise in epidemics, disease, and famine (Al-Mekhlafi 2018; Laub 2016).

One of the causes of the decline in media education programs in Yemen is the politicization of public university administration by the Houthi militia, where they have ordered the arrests of academics, and deprived faculty members and administrators of their salaries. The government’s refusal to pay their wages along with those of employees in several other sectors, whose salaries have been suspended since August 2016, have resulted in labor strikes (Al-Mekhlafi 2018; Laub 2016).

Several media colleges in a number of Yemeni public universities have been bombarded by coalition fighter jets after the Houthis seized them and made them weapons caches (as was the case with Hodeidah University). All documents in the college's archives, including student data and research, were destroyed. In the case of the University of Taiz, the militia seized the site for tanks and the deployment of snipers. The campus became a battlefield, resulting in severe damage to the buildings, many of which were completely flattened, such as the Faculty of Medicine, Graduate Studies, and others (Al-Mekhlafi 2018; Laub 2016).

Despite these circumstances, public universities were only able to accept 15 thousand students. While this represents a good level of enrollment for private universities and institutes in the country, it is a mere fraction of the approximately 150 000 students enrolled in public universities in pre-conflict times (Al-Hadidy 2019).

-

Libya

Geographically, Libya is one of the largest countries in Africa at 1.77 million km2 with a relatively small population of 6.4 million people. The country is rich in oil reserves and despite significant socioeconomic stratification, was relatively wealthy in pre-conflict times. Prior to his 2011 assassination, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi held an iron grip as leader of the country for 42 years. The insecurity that has characterized Libya since the overthrow of Gaddafi, has caused many universities to cease operations and many professors to flee the violence. Today, only twelve out of a total of twenty universities are operational in the country (Musa 2019).

Over the past six years, Libyan universities have turned into violent arenas as feuding factions have attempted to extend their influence amid the chaotic economic and security conditions, the proliferation of arms, and the absence of the rule of law. Since the civil war that erupted in 2014, power in Libya has been divided among three main players; the National Army headed by General Khalifa Haftar, who controls Eastern Libya; the House of Representatives or ‘HoR’, also known as the Tobruk Government; and the Islamic group that found the Libyan conflict as an opportunity and moved to seize control of some Mediterranean coastal cities like Sirte (Libya Country Profile 2019).

Before the civil war, the main function of the media in Libya was to serve the Gaddafi regime, who undertook a sweeping nationalization of media entities when he came to power in 1969. He banned all private media despite stating in his manifesto, The Green Book[2], that the press is a means of expression for Libyan society.

Following the 2011 uprising, Libyan media became diverse in terms of audience and content. New and old newspapers represent the three different groups who exist in Libya today. Private and independent newspapers started to appear; however, journalists are still targeted by different underground militant groups. There are dozens of radio and satellite television networks owned by the state that serve the Libyan population. However, some play a role in the polarization among the different groups and parts of the country. This is in addition to a number of pro-Islamist and pro-revolutionary groups in the west of the country. Journalism and media education were also affected not only by the civil war but also by the fragmented society that is divided between the three current power players (Musa 2019).

Libya has twelve major public universities with media departments or schools of mass communication. This is a considerable number considering the country’s small population. Among the top journalism programs found in Libya are those offered by the University of Benghazi, Tripoli University, the University of Zawia, Azzaytuna University, and the Omar Mukhtar University in Bayda. There are also smaller private programs, but all these offerings suffer from a lack of facilities and trained faculty. Furthermore, the curricula are old and do not serve the fast and innovative changes in the media landscape, with particular reference to digital media (Musa 2019).

-

Syria

The Syrian Arab Republic, located in western Asia, borders Lebanon to the southwest, the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Palestine to the southwest. Syria has a population of 21.1million (2019) with diverse ethnic and religious groups. Syrian Arabs are the largest portion of the population, with Sunni Muslims making up the largest religious group (Syria Country Profile 2019).

Media education began in Syria in 1969, through the Media Training Institute at Damascus University. Eight years later, the department of journalism within the Faculty of Arts and Humanities opened, attracting thousands of students from all Syrian governorates. In 2010, the first media college in Syria opened.

The 2011 uprising broke out as a result of high unemployment, the need for political freedom, and complaints about corruption within the political system. What began as protests eventually gave way to a full-scale civil war with more than 360,000 people dead, 200 members of the media killed, millions of displaced people, and the destruction of many cities (BBC 2019).

Although there have been many efforts by international organizations to stop the violence that was defined by the UN as the worst since World War II, the Syrian situation remains the same. This makes research regarding changes in journalism and media education very difficult with respect to gathering data, conducting interviews, and examining journalism performance. It is worth mentioning that Syria is divided into three different political/media areas or zones where each zone is different than the other. The first zone is controlled by the government; the second represents opposition held territories; and the third represents areas with Kurdish majority (Price, Gohdes, and Ball 2015).

In government-controlled zones, the Syrian media are mostly directed by pro-government news agents, a system that enables the Syrian state to be up to date with events. Today, there are three state-run political daily newspapers (Al-Thawra, Tishrin, and al-Baath) and two private daily newspapers (Al-Watan and Baladna). Headlines of all newspapers usually come from SANA, the Syrian News Agency (Trombetta and Pinto 2019).

However, another form of propaganda was documented; jihadist propaganda, which was found in areas that were under the Islamic State’s (IS) control where all media messages promote Islamic propaganda and are driven from their distorted principles of Islamic Jihad that aim at recruiting young people to its forces (El Damanhoury and Winkler 2018). IS relies heavily on the media - and calls it "media jihad". From Islamic State of Syria and Iraq’s (ISIS) news agencies, the most important is the A’maq News Agency.

The Syrian revolution marked a major turning point for Syrian media, given the explosion in new media, which was accompanied by the widespread use of social media, and talk about a new type of press. The Department of "Electronic Media" was launched in the Faculty of Information in Damascus a year before the revolution started. It was established to keep pace with the development of media, however following the Syrian crisis, and local instability, the proper implementation of the program was hampered, both practically and theoretically (Al-Hadidy 2019). In addition, this forced the program to be limited to theoretical instruction, because of the adoption of “distance education” (Al-Laban 2019).

In zones with a Kurdish majority, it was documented that division arose between the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). This division was reflected in pressure on journalists. Kurdish language was banned until 2011, as was the practice and expression of Kurdish cultural identity, but there has been a surge of independent media, where Kurdish issues are discussed (Price, Gohdes, and Ball 2015; Al-Laban 2019).

Research Methodology and Limitations

In order to assess the status of media and journalism programs on the university level, Yemen, Libya, and Syria were selected as the sample countries for the purposes of the study. The researchers conducted an online questionnaire with experts. The criteria for selecting the sample included mainly academics who teach, or have taught at some point in time in universities in these three states. Experts also included scholars who have previously conducted research relating to journalism education, higher education, and journalism practice in the sample states. In order to maximize the sample size, the online questionnaire was sent to respondents in google documents in both English and Arabic. The questionnaire was comprised of 20 questions, mostly close-ended on a Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree). The questionnaire started off with a briefing statement, consent of identity disclosure, and screening questions to determine the educational level of the interviewees, as well as their prior work relating to Yemen, Libya, and/or Syria’s higher education programs, with particular reference to media and journalism programs. The study was conducted between fall 2018 to spring 2019.

One of the main limitations of the study was pinpointing relevant calibres for interviewing, as well as accessibility to the interviewees. The survey was initially circulated to a purposive non-probability sample of identified experts; 30 experts were targeted through personal contacts and referrals (snowball sample). Additionally, the questionnaire links (English and Arabic) were sent via social media, primarily Facebook, to the accounts of the experts associated with the three major universities in the three countries; University of Tripoli, Libya; Sanaa University, Yemen; and Damascus University, Syria, in addition to a closed Facebook group of scholars and academics called “MDLAB 2019” [Media and Digital Literacy Academy in Beirut]. Out of the 30 plus experts contacted, the researchers received feedback from 12. Some replied expressing disinterest or irrelevance to the topic of study. In future, this study could be further extended to other conflict areas in the Arab region, such as Iraq. More interviewees could also be targeted over a longer time frame to obtain a higher response rate.

The study examined four research questions:

RQ1: Does civil conflict affect the level of journalism education at universities?

RQ2: Does civil conflict affect the university enrollment rates?

RQ3: What are the main challenges facing university level journalism education in Yemen/Libya/Syria?

RQ4: Does civil conflict impact the quality of university curricula?

Findings and Analysis

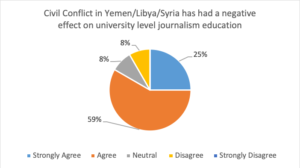

Results show that more than 80% of the respondents agreed (strongly agree and agree) that civil conflict in Yemen/Libya/Syria has had a negative effect on the level of journalism education at universities, while less than 20% were either neutral or disagreed. This idea was confirmed when they were asked about whether it can be said that university level journalism education has improved in Yemen/Syria/Libya post conflict. Again, around 85% of the respondents believed that the quality did not improve, while the rest were neutral.

Graph (1) The effect of civil conflict on university level journalism education

The second part of the survey focused on the challenges facing university journalism education in Libya/Syria/Yemen. Almost 90% referred to the damage of university infrastructure as a main challenge. Almost 85% said that absence of resources to facilitate faculty research, conferences attendance, or otherwise develop, is among the main challenges, and 90% said that high calibre faculty leave the country due to conflict. Furthermore, 100% confirmed that the lack of practical or hands-on training due to limited resources is a challenge. A smaller proportion (75%) believed that it is not safe for faculty and students to go to campus, and 70% of the respondents pointed to the inability of students to afford tuition fees in post-conflict times.

Table (1) Challenges facing university level journalism education in Yemen/Libya/Syria

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| University infrastructure ruined or negatively affected due to conflict | 58% | 33% | 8% | 0 | 0 |

| Teaching resources such as books, labs, and multimedia ruined or negatively affected due to conflict |

50% | 42% | 8% | 0 | 0 |

| Faculty lacking resources to publish their research, attend conferences, or otherwise develop |

50% | 33% | 0% | 17% | 0 |

| High calibre faculty no longer stay in the country due to conflict | 67% | 25% | 0% | 8% | 0 |

| Students cannot afford tuition fees in post-conflict times | 25% | 33% | 25% | 17% | 0 |

| Lack of practical or hands-on training due to limited resources | 50% | 50% | 0% | 0% | 0 |

| It is not safe for faculty and students to go to campus | 25% | 42% | 17% | 17% | 0 |

| High absenteeism rates from students | 33% | 50% | 17% | 0 | 0 |

| High absenteeism rates from faculty | 17% | 67% | 17% | 0 | 0 |

| Faculty salaries negatively affected due to conflict | 83% | 17% | 0% | 0 | 0 |

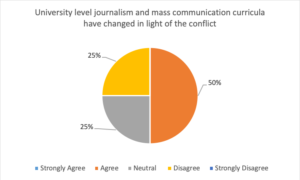

A majority of experts (90%) pointed out that the composition of the faculty involved in university level journalism and mass communication education that has been affected by the conflict. Among the reasons listed were: a lack of money to support qualified people; a reduction in the number of tenured faculty; hiring more part-timers; firing professional faculty and hiring advocates for those in power; and university administration no longer controlling academic or administrative work in accordance with laws and regulations. Around 65% agree that the level of curricula was negatively impacted as a result of the conflict; with around 75% believing that there has been a rise in partisan journalism.

Graph (2) Interviewee opinions on the impact of conflict on university level journalism curricula

Results show that 70% of the respondents agreed that there has been a rise in new forms of journalism such as constructive/humanitarian journalism or trauma and conflict journalism, while 60% agreed that there has been a rise in citizen journalism in light of the conflict, with one of the respondents elaborating that “the security grip prevented the citizen's press from appearing properly. Everyone who expresses a critical opinion is imprisoned and tortured.”

As for education quality and assessment tools, 90% said that they are absent from journalism programs in light of the conflict, 75% agreed that there is a lack of extracurricular activities due to the conflict, and 100% agreed that there is a lack of internships and placements. Moreover, 100% agreed that there is a shortage in technical resources such as equipment, cameras, studios, and labs. In addition, 100% agreed that online learning tools and facilitation are difficult to maintain due to the conflict.

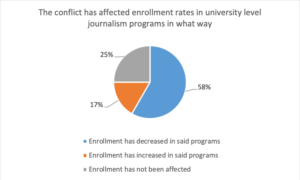

Finally, 58% of the respondents believe that the conflict has decreased enrollment rates in journalism programs, and 75 % believe that it affected graduation rates as well. Respondents were asked to provide any details or statistics they may have regarding registration, attendance, graduate rates from journalism programs during times of conflict in Yemen/Libya/Syria in comparison to pre-conflict times. Among the comments were: “the number of departments and faculties studying journalism has increased without oversight, which has negatively affected the quality of educational outputs; attendance during the conflict reaches almost zero and returns gradually when the conflict subsides; during the pre-conflict period enrollment was better, with the number of students enrolled in the press department reaching 30 and then decreasing after the war to 20, and then seven. The attendance rate currently does not exceed 50%.”

Graph (3) Impact of conflict on university level enrollment rates

Discussion

It can be argued that with the vast loss of jobs, decline in readability of print media, lack of IT, and trained individuals, the field of journalism is in crisis. This trickles down to journalism education, which has also fallen into a state of crisis for these reasons and more. Jobs at legacy newspapers and television are shrinking, and salaries are not competitive. The evolution to digital and new multimedia, while creates new roles and job descriptions for journalists, has resulted in a severe decline in full-time employment in the field with the rise of freelance and non-contracted journalists or one-man crews (Zachary 2014). All of these issues are exacerbated in the context of conflict, like in the cases of the three countries examined here.

Scholars argue that ‘good’ journalism practice mainly relies on expertise gained on the ground, from deep engagement with other disciplines, and multidisciplinary skills. As some journalism schools attempt to add digital tools to the curricula to meet needs of the market, it is still the case that the type of daily journalism consumed by the wider audience is often created by experts with direct mass reach through “blogs, articles, and tweets,” among other platforms (Zachary 2014).

The degradation of media education in the three countries examined are particularly alarming as the media serve vital roles in all societies; they inform, act as watchdogs, set the agenda, and offer a platform for opinion and expression. Moreover, they facilitate building communities by helping people find common causes, and engage in solving societal problems (Owen 2018).

Professional media institutions and instruction are important as relying entirely on new media can disseminate information directly to audiences with minimal or no intervention by editorial or political gatekeepers, or fact-checking mechanisms, thus introducing levels of instability and unpredictability into the communication process. Moreover, new media are more affordable, allowing content to spread without borders. This is why individuals who lack prior journalism education or proper training can still reach audiences at lightning fast speed (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017).

In years past, journalism schools or newsrooms never prepared fledgling journalists, reporters, or photographers on how to understand and deal with war trauma, how to comprehend its effects on both victims and survivors, and how to deal judiciously with trauma especially when reporting on a breaking story. Journalism educators and former reporters, William Coté and Roger Simpson, emphasized the consequences of an absence of proper trauma training for reporters and journalists, and showed how it negatively impacts the profession (Simpson and Cote 2006).

The three countries mentioned in this paper suffer from either a lack of proper journalism and media education programs or poor-quality programs that need to be completely revamped. Civil war in the three countries have complicated the development of journalism and media education programs as sectarian power struggles to control territories and people exist in each country. These groups would like to develop media enterprises supported by well-educated and well-trained media personnel that favor their faction. Under these circumstances there is the need for non-sectarian programs that focus on multi-platform journalism skills, and multi-disciplinary programs that educate students in print, broadcast, multimedia, and social media platforms. Needless to say, this increased emphasis on new telecommunication and media technologies requires resources for equipment, software, and facilities, in addition to qualified and trained individuals as teaching faculty and staff. There is a long road ahead for the development of journalism and media education in Yemen, Libya, and Syria. However, with online and blended education, dual degrees, and international branch campuses in the field of media and communication, these new forms of education can serve as a bridge for these countries to overcome the constraints and challenges that they face and find new models to develop their journalism and media education programs.

[1] A Shia sect that emerged in the eighth century out of Shi'a Islam, and was named after Zayd ibn ʻAlī, the grandson of Husayn ibn ʻAlī. Zaidis make up about 50% of Muslims in Yemen, with the majority of Shia Muslims in the country being Zaydi (Wikipedia).

[2] The Green Book is a short document that Muammar Gaddafi wrote to set out his political philosophy in 1975. It was "intended to be read for all people" (Wikipedia).

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub