Issue 32, summer/fall 2021

https://doi.org/10.70090/ES21PSDJ

Abstract

This article examines the processes by which Jewish Americans become involved in Palestine solidarity activism through a case study of the non-profit organization, Jewish Voice for Peace. This study finds American Jews tend to attribute their support for Palestine to historical events and media rather than planned activities such as interfaith dialogue and awareness-raising initiatives. In addition, despite popular perceptions that understand Jewish Americans’ paths to supporting Palestinians as uniquely arduous, my data suggest that most Jewish activists in the Palestine solidarity movement did not go through major ideological transformations to arrive at their positions. Instead, support for Palestine appears to be more ideologically accessible to Jewish activists than previously theorized. These findings suggest that media can serve as a powerful force to reorganize diasporic commitments and generate transnational support for justice and peace in the Arab world. They also imply that Western support for anticolonial struggles in the Middle East is more likely to be won through accurately reporting on such events rather than more targeted interventions designed to change people’s minds. While many social change organizations devote considerable resources to shifting the thinking of people who oppose their cause, my data suggest that such resources may be better spent mobilizing these groups’ existing bases.

Introduction

In Jewish community centers, schools, and synagogues throughout the United States, American Jews are socialized to identify as members of a diaspora that centers Israel as the Jewish homeland. This process is undergirded by economic and political forces that incentivize American Jews to support the state of Israel which in turn, often lead Jewish Americans to side with Israel in its conflict with the Palestinians. The 2020 Pew study of Jewish Americans, for example, found that 82 percent of Jews consider caring about Israel to be either an important or essential part of their Jewish identity, and the majority of American Jews reported feeling very or at least somewhat attached to Israel (Pew Research Center). Furthermore, while only two percent of American Jews strongly support the Boycott, Divest, and Sanctions (BDS) movement (a clear indicator of political solidarity with Palestinians), 34 percent strongly oppose it.

Despite this context, a growing contingent of American Jews are mobilizing in support of Palestinians’ rights and against the state of Israel. One of the organizations at the center of this activism is Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP). According to their mission statement:

JVP seeks an end to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem; security and self-determination for Israelis and Palestinians; a just solution for Palestinian refugees based on principles established in international law; an end to violence against civilians; and peace and justice for all peoples of the Middle East (Jewish Voice for Peace).

JVP has over 70 local chapters and more than 200,000 supporters. In addition, the organization includes a Rabbinic Council, an Artist Council, an Academic Advisory Council, a youth wing, as well as an advisory board comprised of high-profile public figures. In recent years, JVP has experienced significant growth, with their $400,000 budget in 2009 rising to nearly $3 million in 2021 (Jewish Voice for Peace).

This study analyzes data from a survey of JVP’s national members in order to understand the factors that lead American Jews to support the Palestinian cause. The results of the survey (n=690) show that a majority of JVP members experienced a turning point in their political views on Israel/Palestine. Surprisingly, the results also reveal that Jewish members of JVP experienced ideological turning points at roughly the same rate as non-Jewish members. The data further suggest that most JVP members, both Jewish and non-Jewish, overwhelmingly attributed the cause of their turning points to historical events and the media’s portrayal of those events. These findings speak to the power of media in shaping transnational political action through facilitating ideological transformations among diaspora groups. They also challenge the idea that Jewish identity hinders individuals’ involvement in Palestine solidarity activism. Contrary to past research and popular perceptions, the process of ideological transformation on Israel/Palestine appears to be quite similar for both Jewish and non-Jewish activists in the Palestine solidarity movement.

Diaspora and Zionism

In many ways, Jews are the quintessential diaspora group, with the term often used to directly describe the Jewish people’s millennia-old history of exile and transnational community (Ages 1973). More generally, diaspora refers to any group that is scattered throughout the world from their historical homeland and still maintains a common bond of ethnicity, religion, culture, and/or national identity (Coles and Timothy 2004). Current conceptions of Jewish diaspora that locate this historical homeland within the state of Israel are rooted in the rise of the Zionist movement (Smith 1988). Although early Zionists entertained several locations for the Jewish state, Zionism today generally refers to a Jewish state in Israel/Palestine (Spangler 2015). As such, Zionism is often conceptualized as the return of the Jewish people to their ancient, biblical homeland, Eretz Yisrael. As the Israeli National Anthem goes:

As long as within our hearts The Jewish soul sings,

As long as forward to the East To Zion, looks the eye –Our hope is not yet lost,

It is two thousand years old,

To be a free people in our land The land of Zion and Jerusalem.

Nearly half of American Jews have traveled to Israel, with those under 35 often first traveling there on an organized homeland tour called Birthright. Founded in 1999, Birthright has brought over 750,000 young people with Jewish lineage on free ten-day tours to Israel (Birthright Israel). The program, which targets 18 to 26-year-olds, has become a cornerstone of the Jewish-American experience, and a rite of passage for many Jewish-American millennials (Saxe and Chazan 2008). On these trips, young American Jews are further socialized into supporting the state of Israel through touristic activities that emphasize the Jewish people’s ancient, diasporic connection to the land of Israel.

In contrast to such mainstream approaches to Jewish nationhood, scholars such as Boyarin and Boyarin (2003) have argued for the revival of diaspora, not Zionism, as the central, organizing tenet of Jewish identity. According to Boyarin and Boyarin, Jewish identity should move away from a focus on geography, and instead celebrate the de-territorialized, generational connections among Jews that have functioned to preserve ancient beliefs and traditions. Instead of striving for a “proud resting place,” they suggest that Jewish identity should be defined by a permanent state of dispersal, composed of “perpetual, creative, diasporic, tension” (Boyarin and Boyarin 2003, 103). Stuart Hall (1994) similarly rejects the centrality of collective, physical return in his conception of diaspora. Like Boyarin and Boyarin, Hall prioritizes the experience of diaspora rather than the elimination of diasporic exile. As he explains:

[D]iaspora does not refer us to those scattered tribes whose identity can only be secured in relation to some sacred homeland to which they must at all costs return, even if it means pushing other people into the sea… this is the old, the imperialising, the hegemonising, form of 'ethnicity'. We have seen the fate of the people of Palestine at the hands of this backward-looking conception of diaspora - and the complicity of the West with it. (Hall 1994, 235).

In this quote, Hall directly refers to the ongoing displacement and oppression of the Palestinian people that has resulted from the Zionist movement. While Zionism is often presented as a movement for self-determination of the Jewish people, it is also settler-colonial force, as Palestine was inhabited by over half a million Palestinians, most of whom were forcibly expelled, at the time of Zionist settlement (Halper 2021; Khalidi 1991; Mamdani 2020; Pappé 2007; Sekaily 2015).

As a result of Israeli settler colonialism, Palestinians have now lived under a direct military occupation for over half a century. Numerous international agencies and local organizations have documented the plethora of human rights abuses that occur on a daily basis in the Occupied Territories. For example, despite Israeli citizens’ ability to move freely between Israel-proper and the West Bank, Palestinians’ movement is blocked by hundreds of Israeli checkpoints, road blocks, and closures. These obstructions to Palestinian movement not only cause humiliation and violence, but they also produce economic stagnation, serve as a mechanism for land confiscation, and facilitate Israeli control and surveillance (Gordon 2008; Halper 2021; Khalili 2012). Despite this extreme imbalance of power and the disproportionate number of Palestinian casualties from the conflict, 58 percent of Americans report that they sympathize with Israelis, while only 25 percent more strongly sympathize with Palestinians (Saad 2021). As previously discussed, support for Israel is even more pronounced among American Jews. Rather than simply being a matter of politics, allegiance to Israel is deeply woven into many Jewish Americans’ senses of identity and connections to Judaism (Waxman 2016).

Dissent in the Diaspora

While most American Jews hold favorable views towards Israel, a growing number of American Jews are resisting their communities’ support for Israel and are mobilizing in solidarity with Palestinians. This shift has a generational character, as younger American Jews are diverging from previous generations’ seemingly unequivocal support for Israel (Cohen and Kelman 2010; Sasson 2010; Waxman 2017). According to the Pew study:

Young U.S. Jews are less emotionally attached to Israel than older ones. As of 2020, half of Jewish adults under age 30 describe themselves as very or somewhat emotionally attached to Israel (48%), compared with two-thirds of Jews ages 65 and older (Pew Research Center).

Several scholars attribute this shift to the “distancing hypothesis,” which asserts that young Jews are less attached to Israel than previous generations (Cohen and Kelman 2010). Other scholars, however, maintain that young Jews’ more critical stances represent a deeper engagement with Israel, rather than alienation from it (Sasson et al. 2010; Waxman 2017). Regardless as to which interpretation more accurately describes this trend, Jewish communities across the United States are nonetheless being forced to grapple with growing internal resistance to Zionism.

One of the clearest manifestations of this trend is the recent proliferation of nonprofit organizations that aim to mobilize the Jewish-American population into a more critical relationship towards the Israeli state. In 2007, J Street, the first liberal “pro-Israel, pro-peace” lobby of its size entered the political scene. J Street’s mission statement reads, “J Street organizes pro-Israel, pro-peace Americans to promote US policies that embody our deeply held Jewish and democratic values and that help secure the State of Israel as a democratic homeland for the Jewish people.” (J Street). J Street is adamant about being characterized as a pro-Israel organization, and clearly affirms its belief in the Zionist ideal of a Jewish homeland. Despite this, J Street’s inclusion in “pro-Israel” spaces continues to be a point of controversy, which has resulted in repeated instances of J Street being ousted from Jewish federations, synagogues, and campus groups (e.g., Elsner 2018; Grubaugh 2013; Sokol and Shwayder 2014).

Five years after J Street was founded, Open Hillel, a student-led initiative, was formed after Harvard’s Progressive Jewish Alliance (PJA) was barred from co-hosting a panel with the Palestine Solidarity Committee entitled “Jewish Voices Against the Occupation.” To justify its stance, Hillel (the Foundation for Jewish Campus Life) cited its guidelines of not allowing chapters to partner with, house, or host organizations, groups, or speakers who:

- Deny the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish and democratic state with secure and recognized borders

- Delegitimize, demonize, or apply a double standard to Israel

- Support boycott of, divestment from, or sanctions against the State of Israel

- Exhibit a pattern of disruptive behavior towards campus events or guest speakers or foster an atmosphere of incivility (Hillel, n.d.).

On account of such restrictions, the Open Hillel movement accused Hillel International of creating a litmus test for inclusion in Jewish campus communities based on students’ support for Israel. Students from across the country identified with the group’s critiques, and joined the movement to begin pushing for more inclusive Hillel guidelines while resisting Hillel’s attempts to silence critics of Israel (Open Hillel, n.d.).

Though formed in 1996, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) has experienced massive growth in recent years, with some calling it the fastest growing Jewish organization in the United States (Halper 2021). As JVP continues to increase its membership, its politics have moved steadily to the left. In 2011, JVP members voted to officially endorse Palestinian civil society’s call to support the BDS movement, and in 2018, JVP issued a statement announcing its official opposition to Zionism. JVP’s political stances position them outside the margins of most mainstream Jewish-American approaches to Israel/Palestine, and within the realm of Palestinian solidarity activism. Still, in spite of their relative distance from mainstream Jewish institutional thought, JVP continues to grow as a prominent force for U.S.-based Jewish solidarity with the Palestinian people.

As a political “middle-ground” between J Street and Jewish Voice for Peace, If Not Now was founded in 2014 in response to that year’s major Israeli assault on Gaza. Today, If Not Now serves as an activist home for many young Jewish Americans who oppose Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. While J Street focuses more heavily on institutional channels of change at the government level, and JVP embraces traditional solidarity politics, If Not Now focuses specifically on shifting the political climate within the Jewish American community through education, direct action, and targeted political campaigns. Unlike J Street and JVP, If Not Now directs their activism exclusively towards Jewish-American support for the occupation. For example, If Not Now launched their #YouNeverToldMe campaign to encourage young Jews to share personal stories of problematic Israel education programs as well as their #NotJustAFreeTrip campaign, which focused on critiquing Birthright.

Methods and Case Study: Jewish Voice for Peace

This analysis focuses specifically on Jewish Voice for Peace as a case study to understand how diaspora Jews become involved in Palestine solidarity activism. Since JVP’s members represent some of the most engaged and steadfast Jewish critics of Israel, their paths to activism provide a useful lens into the processes that facilitate engagement with the Palestinian cause among American Jews. Given the ways that many American Jews are socialized to understand themselves as members of a diaspora that should support the Israeli state, this study uses the case of JVP to identify which factors may motivate Jewish Americans to reformulate their relationships to Israel/Palestine. Specifically, I collaborated with staff members at JVP to include a series of questions on their 2015 membership survey that was then used to analyze their members’ political views and ideological transformations on Israel/Palestine.

Jewish members of JVP vary in terms of their relationships to Judaism and how they understand the concept of a Jewish diaspora. In 2017, JVP’s New York chapter published a book entitled, Confronting Zionism: A Collection of Personal Stories (Jewish Voice for Peace NYC 2017). In these stories, JVP members detail the ways that they were raised to see themselves as members of a Jewish diaspora that centered Israel as their homeland. For example, as Talia Baurer writes, “I grew up knowing that Israel was my homeland, that I had deep biblical and historical roots there, and that its existence made me safer in the world – among other insidious mythologies.” In 2019, JVP launched a monthly podcast entitled Diaspora. In the series, various JVP members share accounts of how they were taught to associate their Jewish identity with Israel and to embrace traditional conceptions of Zionism. While there are certainly some members of JVP whose relationships to Judaism and diaspora are less pronounced, these cultural products highlight the large number of JVP members who identify as diaspora Jews.

Based on anecdotal accounts such as those detailed above as well as national polls that demonstrate overwhelming support for Israel within the Jewish community, one would suspect that Jewish activists would experience more arduous paths to supporting the Palestinian cause than non-Jewish Palestine solidarity activists. In order to explore this hypothesis, a series of questions were developed and included on the JVP national membership survey. The first of these questions asked JVP members, “Before becoming a JVP supporter, your political views on Israel/Palestine were:”

- The same as they are today more or less.

- Slightly less critical of Israel.

- Much more supportive of Israel.

- More critical of Israel ([1]).

Respondents who answered “slightly less critical of Israel” and “much more supportive of Israel” were combined to form a single variable of “less critical of Israel before joining the organization.” This created a dichotomous variable to compare those who were previously less critical of Israel to those who had similar views of Israel before joining JVP. Next, respondents were asked, “Was there ever a turning point(s) in your activism or views on Israel/Palestine?” - Yes or No. If respondents answered “Yes,” they were then asked, “What caused the shift in your views/opinions about Palestine/Israel?”

The survey was sent via email to all of JVP’s members (about 6,000 individuals). The survey had around an 11 percent response rate, with 680 people completing the online questionnaire. Of these 680 responses, 501 individuals, who met the criteria for analysis([2]), responded to the question regarding their views on Israel before joining JVP and 487 responded to the turning point question. Of the 332 respondents who answered “yes” to having experienced a turning point, 276 responded to the follow-up question – “What caused the shift in your views/opinions about Israel/Palestine?” The options for this question included:

- Exposure to different media/news outlets

- Seeing/participating in an [organization] or other group’s protest online or in-person

- Attending a local [organization] or other group’s educational event

- Experiencing a particular cultural work – book, film, play, dance, article, etc.

- A specific historical event (war, intifada, etc.)

- An academic experience – class, lecture, etc.

- Meeting/speaking with Palestinians

- An interfaith/dialogue/educational program

- Traveling to or living in Israel/Palestine

- Other (fill in the blank)

Many respondents selected more than one option due to the ‘select all that apply’ nature of the question. About half of the respondents to the survey identified as Jewish, while the other half did not. To compare the responses of these two groups, multivariate logistic regression and t-tests were conducted to analyze the results of the survey.

Findings

Similarities Between Jews and Non-Jews’ Previous Views

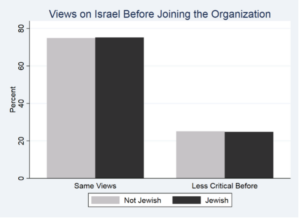

As seen below in Table 1 and Figure 1, Jewish and non-Jewish JVP members’ answers to the question of “Before becoming a JVP supporter, your political views on Israel/Palestine were:” followed similar patterns. About 75 percent of Jewish JVP members had the same level of critique of Israel before joining JVP, whereas about 25 percent were less critical of Israel before joining JVP. Non-Jewish JVP members had an almost identical breakdown, also with about 75 percent having the same level of critique before joining JVP and about 25 percent being less critical before joining the organization.

Table 1: Respondents’ Level of Critique of Israel Before Joining the Organization

| % (n) | |

| Total (n=501) | |

| Same Level of Critique | 75.05 (376) |

| Less Critical Before | 24.95 (125) |

| Jewish (n=250) | |

| Same Level of Critique | 75.20 (188) |

| Less Critical Before | 24.80 (62) |

| Not Jewish (n=251) | |

| Same Level of Critique | 74.90 (188) |

| Less Critical Before | 25.10 (63) |

Figure 1. Views on Israel Before Joining the Organization

Given the ways that American Jews are socialized to support the state of Israel, one would expect that Jewish respondents would have been less critical of Israel prior to joining JVP compared to non-Jewish members. While support for Israel is common across the entire American population, Jewish Americans consistently express higher rates of support for Israel than the general population, and this support is often interwoven into individuals’ sense of a diasporic identity. In a poll administered by the Ruderman Family Foundation of 2,500 American Jews, about two-thirds of respondents reported that they are emotionally “attached” or “very attached” to Israel, and four out of five respondents identified as “pro-Israel” (Winter 2020). As such, one would expect that a significantly larger proportion of Jewish JVP members would have previously been less critical of Israel prior to joining JVP compared to non-Jewish members. Instead, the data showed a similar division between those who were previously less critical of Israel and those who had the same level of critique before joining the organization for Jews and non-Jews.

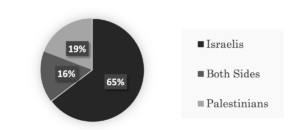

It is also surprising that a large proportion of JVP members (both Jewish and non-Jewish) had relatively similar views on Israel/Palestine before joining JVP compared to their political views today. According to a 2018 Gallup poll (see Figure 2), 65 percent of U.S citizens answered “Israelis” to the question of “In the Middle East, are your sympathies more with Israelis or more with Palestinians?” In contrast, only 19 percent of people answered “Palestinians.” These statistics would suggest that most Americans would need to experience a significant shift in their political thinking to support an organization like JVP, since people in the United States are more likely to be conditioned to support Israelis over Palestinians. In other words, because dominant political frameworks on Israel/Palestine in the United States tend to facilitate widespread support for Israelis over Palestinians, one might assume that someone who came to support an organization like JVP would have previously been less critical of Israel.

Figure 2: 2018 Gallup Poll “In the Middle East, are your sympathies more with Israelis or more with Palestinians?

This finding is especially surprising for Jewish JVP members. According to the aforementioned 2020 Pew Study, 82 percent of Jews consider caring about Israel to be either an important or essential part of their Jewish identity (Pew Research Center). An even clearer indication of Jewish Americans’ support for Israel is seen in the 2018 Jewish Electorate’s Survey, which showed that 92 percent of Jewish voters consider themselves to be some variant of “pro-Israel” (Morganti 2020). Given these statistics, it is particularly noteworthy that so many Jewish members were already critical of Israel before joining JVP.

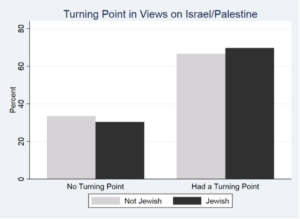

These findings were corroborated by respondents’ answers to the question of whether they experienced a turning point in their views on Israel/Palestine (see Table 2 and Figure 3). Again, one would expect that Jewish respondents would go through turning points at a higher rate than the non-Jewish participants, since most American Jews politically identify with Israel and would therefore need to experience a significant ideological transformation to become Palestine solidarity activists. In contrast, however, both Jewish and non-Jewish JVP members expressed relatively similar rates of experiencing a turning point in their views on Israel/Palestine. While 69 percent of Jews experienced a turning point, 67 percent of non-Jews experienced one as well. Although Jews experienced a turning point at a slightly higher rate than non-Jews, this difference was not statistically significant and therefore does not appear to represent a meaningful difference.

Table 2: Rates of Turning Points

| % (n) | |

| Total (n=487) | |

| Turning Point | 68.17 (332) |

| No Turning Point | 31.83 (155) |

| Jewish (n=242) | |

| Turning Point | 69.42 (168) |

| No Turning Point | 30.58 (74) |

| Not Jewish (n=245) | |

| Turning Point | 66.94 (164) |

| No Turning Point | 33.06 (81) |

Figure 3. Turning Points Among Jewish Versus Non-Jewish JVP Members

Analyzed together with the previous results on criticism of Israel before joining JVP, these findings suggest that contrary to what the existing literature on Jewish Americans’ relationships to Israel would imply, Jews who join organizations that are highly critical of Israel do not appear to have gone through transformative processes at higher rates than the non-Jewish members of those organizations. In other words, diaspora Jews involved in Palestine solidarity organizations do not change their political views on Israel/Palestine before becoming activists at significantly higher rates than the non-Jewish members of those organizations. While these data cannot speak to whether those transformations were perhaps more intense for Jewish respondents – they do reveal a surprising result, that Jewish and non-Jewish activists go through a turning point in their views on Israel/Palestine at similar rates.

Turning Points and Media

In contrast to the first finding that seemed to suggest that most respondents did not go through a significant political transformation regarding their views on Israel/Palestine, most respondents (both Jewish and non-Jewish) answered “yes” to the question of “was there ever a turning point(s) in your activism or views on Israel/Palestine?” As previously discussed, national polls suggest that around 65 percent of Americans express support for Israelis over Palestinians. This aligns with the survey data that shows that around 67 percent of non-Jewish JVP members experienced a turning point around their views on Israel/Palestine. In theory, if JVP members reflect wider attitudinal trends in U.S society, one would expect for about two-thirds of its members to experience a shift in thinking, which is what the data showed.

These findings suggest that there is not a significant difference in terms of the prevalence of ideological turning points between Jewish and non-Jewish Palestine solidarity activists. Jewish activists only experience turning points at a slightly higher rate than non-Jewish activists, and this difference was not statistically significant. These findings therefore challenge recent academic scholarship that centers overcoming Zionism in diaspora Jews’ support for Palestinians (Omer 2019; Schneider 2019; Waxman 2016). In addition, these findings suggest that it is quite common for both Jewish and non-Jewish pro-Palestinian activists to experience a turning point in their views on Israel/Palestine. This result then begs the question of which factors are most likely to facilitate such turning points.

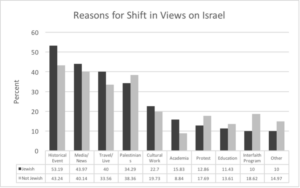

As seen in Table 3 and Figure 4, the most common reasons that respondents attributed to their shift in views on Israel/Palestine were historical events([3]) and media. Given the fact that historical/current events are often learned about through various types of media, it appears that most activists changed their positions on Israel/Palestine because of media coverage of the conflict. Even more so than non-Jews, Jewish activists overwhelmingly attributed their turning points on Israel/Palestine to historical events and the media. Accordingly, these findings speak to the power of media in shaping transnational political allegiances among diaspora groups, in that media coverage of current events may have the ability to reorganize diaspora groups’ political relationships to a base state and to make them more critical of a “homeland” country.

Table 3: Results of T-Test Comparing Jewish and Non-Jewish Reasons for Shift in Views on Israel

| Variable | Means of Non-Jewish Respondents | Means of Jewish Respondents | Difference | t-statistic | Cohen’s d | p-value |

| Historical Event | 0.43 | 0.53 | -0.10 | -1.695 | -0.200 | 0.091* |

| Media/News | 0.40 | 0.44 | -0.04 | -0.657 | -0.077 | 0.511 |

| Travel/Live | 0.34 | 0.40 | -0.06 | -1.128 | -0.134 | 0.260 |

| Palestinians | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.714 | 0.085 | 0.476 |

| Cultural Work | 0.19 | 0.22 | -0.03 | -0.614 | -0.073 | 0.539 |

| Academia | 0.09 | 0.16 | -0.07 | -1.805 | -0.214 | 0.072* |

| Protest | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 1.133 | -0.134 | 0.258 |

| Educational Event | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.555 | 0.066 | 0.579 |

| Interfaith Program | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 2.082** | 0.248 | 0.038** |

| Other | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.269 | 0.150 | 0.206 |

**p<.05, (two-tailed test of significance) *p<.1, (two-tailed test of significance)

Figure 4. Reasons for Shift in Views on Israel

Multiple studies have revealed the ways in which the American media tends to reinforce viewers’ political support for Israel and to promote the dehumanization of Palestinians (Alper and Earp 2017; Jhally and Ratzkoff 2004). Given the ways the American media is slanted towards a positive representation of Israelis and a negative representation of Palestinians, it is noteworthy that nearly half of JVP activists attribute their shifts in thinking to journalistic accounts of the conflict. On the one hand, this suggests that mainstream media sources may evoke sympathy for Palestinians among American viewers, even with their documented bias against Palestinians. On the other hand, this finding speaks to the importance of alternative news sources in educating Americans about the conflict.

Media versus Planned Interventions

Jewish and non-Jewish members’ other reasons for their turning points followed a similar pattern. Both Jewish and non-Jewish activists chose “historical event,” “media/news,” “traveling or living in Israel/Palestine,” as well as “meeting Palestinians” as their top four selections; while “cultural works,” “protests,” and “educational events” came after these four primary selections for both Jews and non-Jews. The two selected reasons that held distinct levels of importance for Jewish compared to non-Jewish activists, were “academia” and “interfaith programs.” While non-Jewish JVP members ranked academia as the least common reason for their turning points, Jewish members ranked interfaith programs as the least common. The only item that produced a statistically significant difference between Jewish and non-Jewish respondents at a p value of less than .05 was the option of “interfaith programs,” with a significantly higher percentage of non-Jewish respondents reporting interfaith programs as shifting their views compared to Jewish respondents. This likely reflects the fact that Israel is frequently addressed in Jewish cultural spaces, whereas non-Jews may only have opportunities to deeply engage with the topic through programs that actively center Jewish and Muslim voices.

Together, these findings not only reinforce the salience of media in facilitating shifts among diasporic populations’ political thinking, but they also suggest the relatively weak influence of planned actions to spark ideological transformations. Rather than trace their turning points to organized interventions such as protests and educational programs, both Jewish and non-Jewish respondents were more likely to attribute changes in their political thinking to major events in Israel/Palestine and media representations of those events. Much of the research on how Jewish Americans come to embrace more critical stances on Israel/Palestine focuses on planned activities such as travel, dialogue programs, interfaith initiatives, as well as cultural and educational opportunities. Concurrently, significant resources are regularly funneled into such programs (Aviv 2011; Kelner 2010; Taylor et al. 2012; Sasson 2010; Saxe and Chazan 2008). Synagogues participate in encounter programs, individuals travel to Israel/Palestine on homeland tours, universities host cultural and academic events, and political groups organize protests and other direct actions to sway public opinion on Israel/Palestine. While each of these types of activities played an important role in some participants’ turning points, historical events and different media sources’ portrayal of those events were overwhelmingly the most frequently selected responses. This suggests that political transformations do not primarily result from planned initiatives such as the ones listed above. Instead, ideological changes appear to be more frequently prompted by socio-historical events and media coverage of those events.

Discussion

Most respondents, both Jewish and non-Jewish, reported that they experienced a turning point in their views on Israel/Palestine. At the same time, a majority of these respondents also reported that their political views on Israel/Palestine were more or less the same before joining JVP. Together these findings suggest that most Palestine solidarity activists (both Jewish and non-Jewish) have held longstanding critical views of Israel. Their turning points then can be largely understood as catalysts to deepen and evoke activism on the issue rather than representing a total reversal of individuals’ political opinions. Nonetheless, it is clear that transformative processes play an important role in many individuals’ paths to Palestine solidarity activism. Past literature would suggest that Jewish activists, in particular, would depend on dramatic ideological transformations to become Palestinian solidarity activists. The results from this study however, demonstrate that Jewish and non-Jewish JVP activists report relatively similar rates of change in their views on Israel/Palestine.

The Mundanity of Jewish Support for Palestinian Rights

These findings generate a number of conclusions that dispel popular perceptions of Jewish activists in the Palestine solidarity movement. First, members of the Jewish diaspora who become critical of Israel appear to follow a similar ideological trajectory as non-Jews. Previous literature would predict that Jewish activists would require a higher rate of ideological transformations in order to join Palestine solidarity organizations than non-Jews. The results of this study reveal however, that Jewish and non-Jewish activists report similar rates of experiencing a turning point in their views on Israel/Palestine, and a similar degree of criticism toward Israel before joining JVP. While theoretical conceptions of critical diasporic engagement with Israel/Palestine emphasize the exceptional character of Jewish dissent, my findings suggest that Jewish identity may not play as large of a role in shifting activists’ political views as previously theorized.

One explanation for this finding is that anti-Zionist diaspora Jews’ more critical viewpoints result from a distinct form of political socialization that differs significantly from most diaspora Jews. For example, perhaps a larger percentage of Jewish solidarity activists grew up in households with parents who were explicitly anti-Zionist, or perhaps anti-Zionist Jews are less likely to have participated in mainstream Jewish institutions like Jewish day school, summer camp, or synagogues. Alternatively, Jewish Palestine solidarity activists may not receive distinct forms of early political socialization compared to other American Jews. If this is the case, one might instead conclude that the barriers to American Jews becoming Palestine solidarity activists are simply not as great as many assume. However, given the fact that only two percent of American Jews support the BDS movement, and that most Jewish JVP members held views that were critical of Israel before joining JVP, it appears more likely that JVP’s Jewish activists represent a subset of the Jewish population in the United States in terms of their political backgrounds.

Although multiple surveys demonstrate that American Jews are more supportive of Israel than non-Jews, the processes by which Jewish Americans and non-Jewish Americans become involved in Palestine solidarity activism appear to be relatively similar. Both Jewish and non-Jewish activists tend to learn about events that trouble them, usually through media, and they become more critical of Israel for committing those acts. In fact, Jewish Americans were even more likely to experience turning points as a result of the media (compared to organized interventions) than non-Jewish activists. While 53 percent of Jewish JVP members attributed their turning points to historical events and 44 percent attributed it to media/news, 43 percent of non-Jewish members attributed their turning points to historical events and 40 percent attributed it to media/news.

Based on the ways that support for Israel is more deeply interwoven into American-Jewish identity compared to the general U.S population as well as the significant resources that are invested into molding Jewish Americans’ positions on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, one would expect that planned activities (as opposed to media and historical events) would have been selected by Jews at a higher rate than non-Jews. Changing one’s mind based on media coverage implies fewer ideological obstacles to such transformations compared to political transformations that result from targeted actions. In other words, if we assume that diaspora Jews are more heavily conditioned to support the state of Israel, then it seems that something more powerful than simply learning about current events would have to take place for transformations in diaspora Jews’ views on Israel/Palestine to occur. This study, however, revealed the opposite: Jewish anti-Zionist activists were more likely to be swayed by media and different news sources as opposed to planned interventions than non-Jewish activists. Again, this could be explained by the fact that either anti-Zionist Jews represent a distinct ideological demographic compared to most American Jews, or that American Jews, in general, are not as predisposed to oppose solidarity with Palestinians as previously theorized.

When it comes to organizing diaspora Jews to be in solidarity with Palestinians, the process of political transformation is not as central as the literature would suggest. American Jews appear to become Palestine solidarity activists in much the same way as non-Jewish Americans. Jewish activists were previously less critical of Israel at the same rate as non-Jewish activists, and the frequency at which diaspora Jews experience turning points in their views on Israel/Palestine is almost the same as non-Jews. Past research has emphasized the deeply emotional processes by which some Jews become more critical of the Israeli state. When it comes to Palestine solidarity activists, however, the data from this study suggest a relatively infrequent and unexceptional rate of troubled paths to criticism of Israel. These findings therefore challenge the assumption that intense processes of political transformation are at the root of most diaspora Jews’ involvement in the Palestine solidarity movement. Concurrently, they raise the possibility that barriers to organizing diaspora Jews in support of Palestinian rights may not be as great as previously theorized.

The Importance of Media in Political Transformation

The second major finding of this study is that exposure to critical and accurate media appears to play a larger role in transforming activists’ ideologies on Israel/Palestine than planned interventions such as educational events, travel, and dialogue programs. One implication of this finding is that social change initiatives that seek to mobilize activists should avoid allocating significant resources to changing people’s mindsets about contentious issues. Instead, activist groups may have more to gain from directing their resources towards mobilizing their allies and existing ideological base. Additionally, contrary to what the literature suggests, American Jews may need even less “handholding” and planned interventions than non-Jews. Jewish activists were more likely than non-Jewish activists to change their minds on Israel/Palestine on account of receiving information from news sources and media compared to planned interventions. This finding suggests that more proactive engagement with alternative media platforms could lead to significant changes in the ways that diaspora Jews think about the conflict. Rather than targeting Jewish individuals through planned interventions, resources may be better spent creating and advocating for fair and comprehensive journalistic accounts of Israel/Palestine. In addition, this finding speaks to the ease with which many American Jews are forming alliances with Palestinians, thereby challenging the idea that Jewish solidarity with Palestine represents an unrealistic political goal.

Another implication of this finding is that activists may be less likely to experience a turning point when they perceive themselves as being told what to think. Compared to the other options listed in Table 3 and Figure 5, media and historical events are the least directive mechanisms for shifting people’s mindsets. As such, turning points on contentious political issues appear most likely to result from experiences where the person has greater agency over their information intake. Similarly, these results speak to the importance of disseminating alternative information versus facilitating interpersonal relationships in cultivating changes in political opinions. Both scholars and peacebuilding practitioners often tout the importance of interpersonal relationships as key ingredients to ideological change (Allport 1954; Hubbard 2001; Maoz 2000; Pettigrew 1998; Ross 2017). In this study however, more people attributed their transformations to learning about events through media channels rather than social factors, i.e. relationships with Palestinians. Of course, it is difficult to determine whether a relationship set the stage for the historical/current event to be impactful or vice versa. Nonetheless, the fact that more people understand their turning points as rooted in historical events and media consumption, compared to meeting individuals of stigmatized groups, means that interpersonal encounters may not have as much of a visceral effect on how people think about the conflict as previously theorized.

One important consideration that should be acknowledged regarding these findings is that these survey results could also reflect which types of activities people typically have access to, more so than the causal, transformative power of each particular activity. For example, a large portion of people in the United States have the ability to consume media, whereas a much smaller number of people have the means to travel to Israel/Palestine or to participate in higher education. As such, these findings may simply reflect the types of mediums that people have access to, more so than these different activities’ isolated impact. Nonetheless, even if these results are simply a reflection of access and availability, they are still useful in that they reveal how activists understand their own pathways to engagement. Furthermore, they quantitatively reflect which events are most likely to provoke change among potential activists within current social and economic constraints, thereby offering practical insights into the ways that transnational social movements may grow and succeed.

Conclusion

The findings of this research suggest that Jewish solidarity with Palestinians is a more organic political orientation for many American Jews than previously theorized. Not only were Jewish activists just as likely as non-Jewish activists to hold critical views of Israel before joining JVP, but Jewish activists were more likely than non-Jews to shift their thinking on Israel/Palestine because of external events and media as opposed to planned interventions. A such, Palestine solidarity organizations may benefit from moving past a strategic focus on persuading American Jews to become more critical of Israel and instead shift towards a greater emphasis on spreading information about the occupation and mobilizing their existing supporters.

These findings also add a new layer of critique to the scholarship on planned interventions such as dialogue and peace education programs (Aouragh 2016; Abu-Nimer 2001; Gawerc 2006; Hubbard 2001; Maoz 2000; Ross 2017; Rothstein 1999; Schneider 2019). In addition to reinforcing power imbalances and being indebted to neoliberal donors, the data from this study suggest that such programs play a marginal role in building the bases of more radical organizations. In contrast to anecdotal stories of major political transformations among Jewish Palestine solidarity activists, most activists in this study appear to have long held critical views of Israel. Furthermore, when activists did experience a major shift in their thinking, it was more often due to media coverage of current events than interfaith or dialogue programs.

This study offers several broad implications that extend beyond the specific context of diaspora Jews’ solidarity with Palestine. First, media remains a powerful tool to generate solidarity with oppressed populations in the Global South. Most people who become activists do not need to be coerced into supporting such causes, instead, they need access to accurate information that informs them of injustices occurring abroad. This conclusion leads to the second wider implication of this study. Organizations that strive for radical social change may have more to gain from strengthening their existing bases than attempting to dramatically shift the mindsets of their opposition. In other words, organizations should not focus on converting its opponents at the expense of supporting those who are currently engaged in struggle. Finally, in contrast to dominant approaches to the subject of Jewish support for Palestinians, this study suggests that Jewish solidarity with Palestine is not typically the result of hard-won ideological conversion, it is instead an accessible, and even obvious, political orientation for many American Jews.

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the support of Samantha Brotman at Jewish Voice for Peace as well as Jamie Baum, whose 2018 senior thesis provided the groundwork for this article’s statistical analyses.

Works Cited

Abu-Nimer, Mohammed. 2001. Reconciliation, Justice, and Coexistence: Theory and Practice. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Ages, A. 1973. The Diaspora Dimension. Dordrecht: Springe.

Allport, Gordon. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Boston: Beacon Press.

Alper, Loretta and Jeremy, Earp. 2017. “Occupation of the American Mind.” Retrieved Feb 19, 2018.

Aouragh, Miriyam. 2016. “Hasbara 2.0: Israel’s Public Diplomacy in the Digital Age.” Middle East Critique 25, no. 3: 271-297.

Avineri, Shlomo. 1979. “Zionism as a National Liberation Movement.” The Jerusalem Quarterly 10: 133-144.

Aviv, Caryn. 2011. “The Emergence of Alternative Jewish Tourism.” European Review of History 18, no. 1: 33-43.

Birthright Israel. 2022, February. Our Story https://www.birthrightisrael.com/about-us

Boyarin, Daniel, and Jonathan Boyarin. 2003. “Diaspora: Generation and the Ground of Jewish Identity.” Critical Inquiry 19, no. 4: 693-725.

Cohen, Steven M., and Ari Y. Kelman. 2010. “Thinking About Distancing from Israel.” Contemporary Jewry 20, no. 2-3: 287-296.

Coles, Tim, and Timothy, Dallen J. 2004. Tourism, Diasporas and Space. London: Routledge.

Elsner. 2018. “I’m Leaving My Synagogue of Three Decades — Over J Street” The Forward. https://forward.com/scribe/396949/im-leaving-my-synagogue-of-three-decades-over-j-street/

Gawerc, Michelle. 2006. “Peace-Building: Theoretical and Concrete Perspectives.” Peace & Change 31, no. 4: 435-478.

Gelvin, James L. 2005. The Modern Middle East: A History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, Neve. 2008. Israel’s Occupation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Grubaugh, Connor. 2013. “Jewish Student Union votes to deny membership to J Street U” The Daily Californian. https://www.dailycal.org/2013/10/08/jewish-student-union-votes-deny-membership-j-street-u/

Hall, Stuart. 1994. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” In Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory, edited by Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Halper, Jeff. 2021. Decolonizing Israel, Liberating Palestine: Zionism, Settler Colonialism, and the Case for One Democratic State. London: Pluto Press.

Hillel. n.d. Hillel Israel Guidelines. Accessed February, 2022. https://www.hillel.org/jewish/hillel-israel/hillel-israel-guidelines

Hirschhorn, Sarah Yael. 2015. “Israeli Terrorists, Born in the U.S.A.” The New York Times, September 4, 2015.

Hubbard, Amy S. 2001. “Understanding Majority and Minority Participation in Interracial and Interethnic Dialogue.” In Reconciliation, Justice, and Coexistence: Theory and Practice, edited by Mohammed Abu-Nimer. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Jhally, Sut, and Bathsheba Ratzkoff, dirs. Peace, Propaganda & The Promised Land. Media Education Foundation.

J Street. n.d. About Us. Accessed February, 2022. https://jstreet.org/about-us/#.Yfw41fXMLDE

Jewish Voice for Peace NYC. 2017. Confronting Zionism: A Collection of Personal Stories. Jewish Voice for Peace.

Jewish Voice for Peace. n.d. Mission. Accessed February, 2022. https://jewishvoiceforpeace.org/mission/

Jewish Voice for Peace. n.d. 5781 Annual Report. Accessed February, 2022. https://report.jewishvoiceforpeace.org/

Kaplan Sommer, Allison. 2017. “The Jewish Voice at the Heart of the Boycott Israel Movement.” Ha’aretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/the-jewish-voice-at-the-heart-of-the-boycott-israel-movement-1.5453944

Kelner, Shaul. 2010. Tours that Bind: Diaspora, Pilgrimage, and Israeli Birthright Tourism. New York: New York University Press.

Khalidi, Rashid. 1991. The Origins of Arab Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Khalili, Laleh. 2012. Time in the Shadows: Confinement in Counterinsurgencies. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Maltz, Judy. 2018. “Sharply Divided Over Trump, Western Wall and Settlements, Survey Shows.” In Our Jewish Life: The Changing American-Jewish Commitment to Israel, Ha’aretz.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 2020. Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Maoz, Ifat. 2000. “Power Relations in Intergroup Encounters: a Case Study of Jewish-Arab Encounters in Israel.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 24: 259-277.

Morganti, Caroline. October 29, 2020 “Are 85% of Jews Really Zionists?” Jewish Currents. https://jewishcurrents.org/are-95-of-jews-really-zionists/?fbclid=IwAR1W9e4N0O5YYmxJHfcHXxILqgOEA9-NjToJR5KK8e2n8jWp2NEJmc4Eqb4

Pew Research Center. May 11, 2021. “Jewish Americans in 2020”

Omer, A. 2019. Days of Awe: Reimagining Jewishness in Solidarity with Palestinians. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Pappé, Ilan. 2007. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oxford: Oneworld.

Pettigrew, Thomas. 1998. “Intergroup Contact Theory.” Annual Review of Psychology 49: 65–85.

Pressman, Jeremy. 2016. “A Brief History of the Arab-Israeli Conflict.” https://jeremy- pressman.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1324/2015/05/arab-israeli-history- 3.0.pdf

Ross, Karen. 2017. Youth Encounter Programs in Israel: Pedagogy, Identity, and Social Change. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Rothstein, Robert. 1999. “In Fear of Peace: Getting Past Maybe.” In After the Peace: Resistance and Reconciliation, edited by Robert L. Rothstein. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Saad, Lydia. 2021, March. “Americans Still Favor Israel While Warming to Palestinians” Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/340331/americans-favor-israel-warming-palestinians.aspx.

Sasson, Theodore. 2010. “Mass Mobilization to Direct Engagement: Jewish-Americans’ Changing Relationship to Israel.” Israel Studies 15, no. 2:173-195.

Saxe, Leonard, and Chazan, Barry. 2008. Ten Days of Birthright Israel: A Journey in Young Adult Identity. Waltham: Brandeis University Press.

Schneider, E. M. 2019. “Now That I’ve Seen Their Faces: Contact, Social Justice, and Tourism in Israel/Palestine.” PhD diss., UC Santa Barbara.

Sekaily, Sherene. 2015. Men of Capital: Scarcity and Economy in Mandate Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Smith, Charles D. 1988. Palestine and the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Education.

Sokol, Sam and Maya Shwayder. 2014. “J-Street ‘disappointed' by Conference of Presidents rejection” The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/jewish-world/jewish-news/j-street-disappointed-by-conference-of-presidents-rejection-351049

Taylor, Judith, Levi, Ron, and Dinovitzer, Ronit. 2012. “Homeland Tourism, Emotion, and Identity Labor.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 9, no. 1: 67-85.

Tessler, Mark. 2009. A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Waxman, Dov. 2016. Trouble in the Tribe: The American Jewish Conflict Over Israel Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Waxman, Dov. 2017. “Young Jewish-Americans and Israel: Beyond Birthright and BDS.” Israel Studies 22, no. 3: 177-199.

Winter, Stuart. 2020. “Rather than drifting away, over two-thirds of US Jews feel tie to Israel – poll” The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/rather-than-drifting-away-over-two-thirds-of-us-jews-feel-tie-to-israel-poll/

([1]) When conducting the analysis, a small number (<50) of respondents who selected this option were excluded in order to focus the research on those individuals who came to support Palestine after previously being more supportive of Israel.

([2]) Individuals who did not answer the question of Jewish identity, who were not from the United States, and who were more critical of Israel before joining JVP were not included in the analysis.

([3]) e.g., Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Sabra and Shatila, First Intifada, 6-day war, Camp David in 2000, 2012 and 2014 invasions of Gaza.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub