Issue 27, winter/spring 2019

https://doi.org/10.70090/CC27ALJB

Abstract

In December 2013, the pan-Arab TV station Al Mayadeen orchestrated a big public celebration of the former female fighter Jamila Bouhired. In this article, I analyze Al Mayadeen’s celebration of Bouhired as an iconization (Khalili 2009) and investigate how the TV station uses the icon Bouhired to facilitate a particular reading of the past that supports a contemporary political agenda. I investigate how secular icons can take form, develop, and not least become an important tool in a mediatized world where political contests to a large degree are a battle over the symbolic world. By understanding the iconization of Bouhired we understand how the TV station (and the political fractions it represents) reads the past, understands the present, and envisions the future. During the celebration, the Arab uprisings of 2011 are dismissed, while Hezbollah is promoted as the heir of Bouhired’s progressive resistance legacy.

Introduction

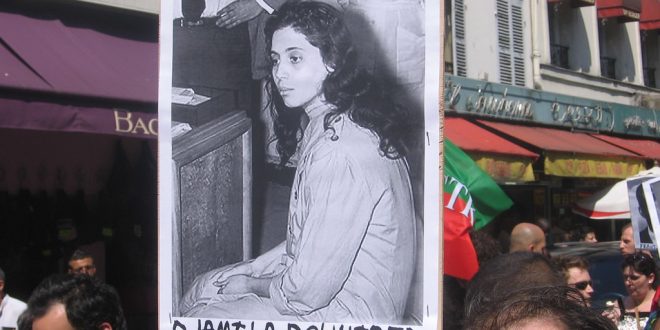

In the late autumn 2013, billboards on the streets in Beirut were displaying Jamila Bouhired, a former Algerian female fighter, together with the logo of Al Mayadeen, a pan-Arab news TV station. The posters were advertising Al Mayadeen’s big celebration of Bouhired on the 3rd of December, 2013 at the UNSECO Palace in downtown Beirut. As a young woman, Jamila Bouhired had been a renowned public figure in the Arab world due to her participation in the Algerian war. She had been almost forgotten by the media in 2013, when al-Mayadeen decided to orchestrate a big public celebration of her life with an impressive entertainment show. The event brought together artists and activists from the Arab world and beyond who contributed to the celebration on stage while other prominent names from the region travelled to Beirut in order to attend the show. On the following day, an additional although smaller ceremony was held in the former Hezbollah command centre in the south Lebanese village Mleeta. Both events were broadcast live on Al-Mayadeen.

While this surely was a campaign aimed at spreading awareness about a nascent TV network, the focus on Jamila Bouhired indicated that this was more than just a straightforward PR campaign of a TV station. So, why did the station choose to bring this grand old lady from the past back into the spotlight? This article understands Al Mayadeen’s celebration of Bouhired as an iconization (Khalili 2009) or, one could argue, a re-iconization, as Bouhired earlier in her life had iconic features. It investigates how the TV station uses the iconization of Bouhired to establish a nostalgic worldview and promote a contemporary political agenda about dismissing the Arab uprisings and promoting Hezbollah as the heir of Bouhired’s legacy. By understanding the iconizeation of Bouhired we can understand how the TV station—and the political fractions it represents—reads the past, understands the present, and envisions the future. Thus, the article investigates the iconization as an example of how political fights play out in a symbolic world where images, music, monuments—and secular bio-icons (Ghosh 2011)—play the central roles.

Al Mayadeen remains almost uncovered within academic research, thus this article contributes with new empirical knowledge about an important pan-Arab news station. Furthermore, the article investigates how secular icons can take form, develop, and not least become an important tool in a mediatized world where political contests to a large degree are battles over the symbolic world. I argue that a secular icon can facilitate a particular reading of the past that again can be used to promote a contemporary political agenda, and that monopolizing the reading of an icon is a strategy for political influence and power.

This article draws on three years research of Al Mayadeen and its broadcasts including ethnographic fieldwork at and around the station (Crone 2017). The data was collected beginning September 2013 and the proceeding three years, closely following Al Mayadeen’s broadcasts, while prioritizing cultural or societal programmes and media events over newscasts. This may seem a controversial choice when working with a news station but my aim was to move beyond a superficial description of political agendas or alliances of the station. Rather, the goal was to investigate the ideological core, or overall worldview, that would make certain political positioning seem the only logical or righteous outcome. Thus, the stations use of icons, cultural figures, images and slogans, intellectual capital, nostalgia, and other symbolic elements that together form an ideological discourse were explored.

In addition to content analysis of programmes, interviews were conducted during four trips to Beirut between 2013 and 2015 in order to meet and interview individuals working at and around Al Mayadeen.[1] Though access proved to be challenging, I succeeded in visiting the main office building several times, sitting in on shoots, conducting interviews with 13 staff members, three former staff members, and seven stakeholders. Some of the interviewees, I met once for an official interview, others I met on several occasions, at times in their homes. Finally, relevant survey data was acquired from the Ipsos office in Beirut about audience ratings and viewership demographics. It is this combined knowledge that forms the basis of the present article.

Below is an introduction of Al Mayadeen, following an explanation of the concept of secular icons. Later, Al Mayadeen’s iconization of Bouhired is examined in detail as is how nostalgia plays a central role in Al Mayadeen’s worldview as well as in its promotion of political agendas.

Al-Mayadeen

Al Mayadeen was launched on June 11, 2012, and its establishment was closely linked to the political developments and conflicts in the Arab world following the uprisings of 2011. More concretely, Al Mayadeen was the result of Ghassan bin Jeddo’s decision to leave Al Jazeera back in April 2011. Bin Jeddo was one of Al Jazeera’s most prominent figures, but in the midst of the Arab uprisings and the changing political landscape, Jeddo was frustrated with Al Jazeera’s proactive coverage of the uprisings in Syria. He accused the network of having sold out of its professionalism and of having turned into a tool for political mobilization (As-Safir 2011). When Jeddo announced his plans to launch a new TV station, it was with the promise of a more objective and professional media. Nevertheless, accusations about bias and being the mouthpiece of Tehran or Damascus were intense even before Al Mayadeen started broadcasting. Thus, from its first day, Al Mayadeen has played an active role in a politicized and polarized Arab media landscape, manoeuvring in a highly fragmented Arab public.

Even though, Al Mayadeen’s official answer to the question about who finances the station is “Arab businessmen”, there are many indications that Iran in one way or another is providing the main source of funding. In addition to an editorial line that often aligns with the interests of Tehran, the central persons around Al Mayadeen have a history that connects them to either Al Manar, Hezbollah, or the Syrian regime (Crone 2017: 70-74). Furthermore, Al Mayadeen’s main office in Beirut is situated between the Iranian cultural centre and the Iranian embassy in Bir Hassan, a Southern district of Beirut that connects the city with the famous Hezbollah-dominated southern suburb Dahye. In the streets around Al Mayadeen, several Iranian-funded TV stations[2] are located, which further underlines the suggestion that Al Mayadeen is part of an Iranian media sphere. A former media professional from the station even told me that that the furniture and equipment was the same in all the TV headquarters (including Al Mayadeen’s) in the area—yet another way of underscoring that the backer was likely the same (personal interview, Beirut, November 2014).

From the first day, Al Mayadeen has worked with a clear agenda of fighting Sunni Islamism and denouncing the Arab uprisings as initiated by the West with the aim of weakening the Arabs. Al Mayadeen strives toward bringing Palestine and the traditional resistance movements back into the media spotlight in order to counteract what the station considers the loss of focus generated by the Arab uprisings. When talking to the staff members, the continued struggle for Palestine and resistance against Israeli occupation was without comparison the strongest uniting factor. In addition, Al Mayadeen presents itself as “a voice in the revolutionary southern world,” that is “biased towards the South.” This translates into a close collaboration with the pan-Latin American TV station TeleSur (based in Venezuela) and a general promotion of Latin America and its revolutionary legacy.

Though, Al Mayadeen probably depends more on Iranian than Arab money, the station nevertheless plays an important role in the Arab media landscape, especially in the Levant.[3] In contrast to the Arabic language Iranian state channel Al Alam that clearly propagates Iranian state interests, the ambition behind al-Mayadeen is different. It is promoting itself as the protector of true Arab values, as the progressive Arab voice that stands up against the regressive values of the Gulf and Islamist groups on the one hand, and the imperialistic ambitions of the West on the other. I argue that the station targets the parts of the TV audience that feel threatened by the growing Sunni Islamization of society (led by Saudi Arabia) and alienated by the young progressive activists that initiated the Arab uprisings (Crone 2017).

In different ways, Al Mayadeen experiments with reconnecting the resistance struggle against Israeli occupation and Western colonialism to leftist ideologies as a counterweight to the general Sunni Islamization of the resistance movement that has taken place since the 1980’s. The station does that through its celebration of the Latin American resistance legacy that is dominated by secular leftist ideologies as well as through its reproduction of art (music, poetry, etc.) and cultural figures associated with the Arab secular resistance movements of the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s. The Bouhired celebration is an example of how Al Mayadeen strives to evoke a nostalgic longing for a bygone Arab time of resistance and progressive ideologies and by suggesting restoration of the past as a plausible way forward.

Below is an engagement with the concept of the secular icon, as I argue that the Bouhired event should be understood as an iconization (or re-iconization) of Bouhired. This can help us understand not only the worldview of Al Mayadeen but also how the station tries to utilize an icon to facilitate a particular reading of the past. This reading is dominated by nostalgic sentiments and employs a general longing for a lost time and lost identity as a strategy to promote a political agenda.

The concept of the secular icon

Historically, the concept of icons has been connected to religious traditions of worship but in contemporary times, David Scott and Keyan G. Tomaselli (2009) argue, cultural icons also include secular icons from real life that, through time, obtain a “certain exemplary status” (Scott and Tomaselli 2009: 18). Today, in ways facilitated by our mass-mediated society, non-religious images, songs, cultural figures, and political leaders have obtained icon-like status. Along the same lines, Bishnupriya Ghosh investigates in her book Global Icons: Apertures to the Popular (2011) how living people can develop into highly visible public figures, capable of moving the public and sometimes even initiating social change. The public figures, which she refers to as “bio-icons” (ordinary humans ‘just like us’ and not saints), transform from being ordinary people into symbols or “powerful signs”, and thus function as sources of inspiration. Ghosh underlines the importance of mass media, which offers a platform for these bio-icons to be shaped, promoted, and conceived.

In a Middle Eastern context, secular cultural icons or bio-icons have played an important role in political life in the twentieth century. Charismatic state cult leaders like Hafez Al Assad (Wedeen 1999) and Kemal Atatürk (Ozyurek 2006); leaders like the late Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, Lebanese politicians like Michel Aoun (Lefort 2015) and Bashir Gemayel (Haugbølle 2013b); cultural figures such as Fairouz (Stone 2008) and Ziad Rahbani (Haugbølle 2016b); and resistance leaders such as Hassan Nasrallah (Lina Khatib, Matar, and Alshaer 2014) and Yasser Arafat have, in different ways, formed “a pivotal point in the production of various kinds of mass-mediated publics.” (Haugbølle and Kuzmanovic 2015: 5) In particular, in contexts where secular powers have attempted to counteract religiously identified opposition movements, the iconization of secular figures has been a significantly employed political strategy (Bandak and Bille 2013: 15–16). Historically, in the Arab world, the number of secular female icons has been limited, but within the independence struggle, they have played a role as key symbols. Jamila Bouhired is one such example.

Thus, in addition to being a source of inspiration or a carrier of active social demands, as Ghosh explains, an icon can equally be employed as important ammunition in political power games that play out in symbolic spheres. In our mediatized modern world where “symbolism [is] becoming an established means of conveying political messages,” (Khatib 2013: 6) as Lina Khatib argues in, Image Politics in the Middle East (Khatib 2013), the struggle over the meaning of a symbol becomes central. In line with this Lisa Wedeen writes in her remarkable book Ambiguities of Domination (Wedeen 1999) that “politics is not merely about material interests but also about contests over the symbolic world, over the management and appropriation of meanings.” (Wedeen 1999: 30) Part of the symbolic struggle is the struggle over how to read the past. In his work on the Arab left’s use of secular icons, Sune Haugbølle argues that the employment of secular icons can facilitate a particular understanding of the past. Thus, icons can be used strategically in struggles over how to read the past. Haugbølle notes: “Maintaining the possibility of a secular reading of history is one of the challenges facing the Arab left (…) such readings make use of icons that refer back to a time when secular readings of history were taken for granted.” (Haugbølle 2013b: 256)

Thus, creating and not least monopolizing the reading of an icon is a strategy for political influence and power. I argue that Al Mayadeen’s iconization of Bouhired should be understood within this frame.

An important aspect of an icon is its detachment from concrete contemporary political developments. An icon is above ongoing political power struggles, empty of specific political content, but is, yet, a symbol of certain values or qualities, which can be interpreted in different ways depending on agendas and worldviews. In this connection, Laleh Khalili notes, “Iconization transforms a concrete event, object, or being into a symbol. It is the process by which an event is decontextualized, shorn of its concrete details and transformed into an abstract symbol, often empty, which can then be instrumentalized as a mobilizing tool by being ‘filled’ with necessary ideological rhetoric.” (Khalili 2009: 153) As will be explained in the following, this was the case for Bouhired in spite of her former fame. In 2013, years had passed since Bouhired had been active on the battlefield, just as the media attention had faded.

Jamila Bouhired participated actively in the Algerian war of independence, as a member of the Front de Liberation National (FLN). In 1957, together with two other FLN female members, she planted a bomb in a French restaurant, which caused the death of 11 civilians. She was later arrested, tortured by French soldiers, and sentenced to death (a sentence that was never carried out). In spite of the torture, she never divulged information about her FLN comrades, which made her an international symbol of resistance. Jamila Bouhireds’ engagement in the Algerian war combined with the promotion of her in the media had already, by the end of the 1950’s, turned her into a celebrated public figure representing the anti-colonial struggle.

In 1958, at the height of Egypt’s pan-Arab Nasserist phase, the movie Jamila the Algerian was released. It was one of Egyptian director Youssef Chahine’s first politicalized films and told the story of Jamila Bouhired’s involvement in the Algerian war of liberation. The film and, not least, the figure of the young female freedom fighter “contributed to the third-worldist anticolonial rhetoric of the time.” (Shafik 2015: 105). Likewise, Arab media closely followed Jamila Bouhired and her female comrades in arms on their official visits to friendly-minded states as representatives of the FLN and as “symbols of the youthfulness and modernity of the Algerian revolution.” (Vince 2009: 160). One of the most important trips was Bouhired’s travel to Cairo in 1962 to visit then president, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

While the 1960s constituted the heydays of Bouhired, in the following decades, her fame faded and her name was converted into a subcultural figure within certain feminist or socialist circles, almost forgotten by the broader public.[4] In spite of Bashar Al Assad granting Bouhired the Syrian Order of Merit of Excellent Degree in January 2009, later the same year, Bouhired made a public appeal to the Algerian president and the Algerian people asking for recognition and economic support.[5] Once an icon, she had lost her appeal as the political and ideological reality surrounding her changed. Thus, in 2013, Bouhired had been “decontextualized, shorn of her former concrete political affiliations or other details and transformed into an abstract symbol ready to be instrumentalized as a mobilizing tool by being ‘filled’ with necessary ideological rhetoric,” as Laleh Khalili describes the process of iconization. Below, I analyse Al Mayadeen’s framing of Bouhired as it relaunched her as a public figure, warming up to the celebration and bringing her back into the spotlight.

It was not only billboards on the streets of Beirut, which advertized Al Mayadeen’s celebration of Bouhired. In the weeks and days leading up to the event at the UNESCO Palace, several small spots broadcasted repeatedly. Al Mayadeen promoted Bouhired and the revolution of a million martyrs as the station refers to the Algerian war of independence.[6] The spots were a mix of old footage and new graphics and brought together nostalgic images from the past with a confirmation of its continued relevance. Together, they recaptured the life story or ‘the formalized bio’(Ghosh 2011) of the forgotten heroine Bouhired very much in line with how she was portrayed in the past.

The spots portrayed Bouhired as having heroic strength and an uncompromising attitude and referred to her as either munaḍila [struggler] or mujahada [fighter], two different words for female fighter.[7] One of the spots evolved around Bouhired’s famous statement while under torture in French custody - I know that you will sentence me to death (…) but you will not prevent Algeria from becoming free and independent. The contrast between the cruelty of the French colonial power and young beautiful woman’s courage was framed to leave no one in doubt about the level of her commitment. Through the use of old footage of Che Guevara and Gamal Abdel Nasser, Bouhired was placed next to established global icons and framed within an international narrative of anti-imperial struggles. In addition, Aleida Guevara, daughter of Che Guevara, was introduced when one of the spots showing old footage of Che Guevara ended with the voice of Aleida stating My father is the man who taught me to live with dignity, thus confirming the value of his struggle as well as her own continuation of his legacy.

Another framing of Bouhired and the upcoming event was created when Al Mayadeen hosted female fighters from Arab independence struggles in the station’s debate programmes and talk shows, placing Bouhired within a particular narrative about secular Arab female fighters from the past. Thus, during the week of the event, the following guests appeared at Al Mayadeen: the Palestinian resistance fighter Fatima Barnawi, who placed a bomb in a cinema in Jerusalem as a protest against the screening of a movie celebrating the 1967 war (Khasa Al Mayadeen, 02.12.2013); Laila Khalid, also Palestinian, who participated in the hijacking of an airplane in 1969 (ALM, 28.11.2013); the Algerian former fighter Louisette Ighilahriz (ALM, 28.11.2013); as well as Tereza al-Halasa, a former member of the Palestinian resistance organisation Black September, who had participated in the hijacking of the Sabena Airplane on its way from Vienna to Tel Aviv (Ajras Al Mashreq, 01.12.2013). At Al Mayadeen, Bouhired’s methods and those of her female peers are never questioned, as their struggle is considered just and incontestable. The methods employed are—in line with the prevailing attitude in the mid-twentieth century—seen as “an appropriate weapon of the weak in combating human rights violations in nations suffering under forms of colonialism that had clear internal and external beneficiaries.” (Meister 2002: 92)

This line of guests placed Bouhired within a broader narrative about anti-colonial struggles, a narrative that not only includes the legacy of resistance but also the progressive values that this movement promoted (at least rhetorically) regarding women’s rights (Khalili 2009: 20-21). In spite of the hyper-masculine form of heroism that typically dominated the radical ideology of Third World liberationists of the 1960s and ‘70s, female warriors on several occasions obtained almost iconic status. They became symbols of progressive values and “a measure of the advancement or the backwardness of a culture.” (Katz 1996: 93) Thus, today, Bouhired facilitates a reading of the past that highlights a particular set of values such as modernity and progressiveness just as Al Mayadeen’s recognition of her becomes an indicator of the station’s progressive culture and worldview.

Closely linked to the promotion of the legacy of these women, was Al Mayadeen’s discrediting of contemporary time. An example is how the host, Ghassan Shami, expressed his appreciation and discontent respectively, in the episode staring Terez Al Halasa: In these dark times, women like Terez Al Halasa and her comrades Rima Tanous and Jamila Bouhired and all the women who participated in the furnace of liberation are torches of light much needed for us and our societies which are becoming increasingly masculine and patriarchal (Ajras Al Mashreq, 01.12.2013). Hence, to re-launch and celebrate a female revolutionary from the past, in a time of revolts in the Arab world, is not a salute to the current uprisings. On the contrary, Bouhired is used to dismiss contemporary developments and create “a nostalgic take on modernity,” to use the words of Özyürek (Ozyurek 2006: 19). Thus, Al Mayadeen frames Bouhired as representing the modern and progressive Arab history of revolution and resistance that the station wants to revive.

Summing up, the short spots and special programmes not only promoted the event but also created a nostalgic narrative about a proud but bygone age of Arab history. Together, the broadcasts leading up to the event placed Bouhired within a particular frame that glorified armed struggle against Western imperialism, praised personal sacrifice for the homeland (underscored by Bouhired being a woman), and reminded the viewer of the greatness of their collective past. The scene was set for the big event…

The central happening and climax of the celebration was the evening show at the UNESCO Palace, with performances by famous artists, greetings from many more, and the attendance of several prominent figures among the audience. Below, I analyze the evening of celebration as an iconization or even re-iconization of the old lady Jamila Bouhired.

A warm-up hour on TV, hosted by a well-known face of Al Mayadeen, the journalist Kamal Khalaf, led up to the live show itself. During this hour, a serious and expectant atmosphere was built up through a mix of Khalaf’s conversations with guests in the studio and live reports from the entrance hall at the UNESCO Palace as the audience arrived. An important element in both the show itself and the hour from the studio was the presence of renowned public figures from all around the Arab world. Celebrities are, of course, always material for a media outlet, but here they also served the purpose of legitimizing the iconisation set-up. It added to the atmosphere that discussion with guests in the studio were regularly put on hold in order to document the arrival of well-known (as well as less well-known) Arab public figures to the event; all of whom of course expressed their praise of Bouhired, the struggle she fought, and the time she represents.

The show itself was kicked off by the two Al Mayadeen hosts, Aula Malaah and Ahmad Abu Ali, who entered the UNESCO Palace stage accompanied by music and light. The cameras showed a full theatre hall and zoomed in on some of the most prominent guests in the front rows: then Lebanese foreign minister Adnan Mansour, then Lebanese minister for public health Hassan Khalil, Aleida Guevara, Ghassan bin Jeddo, and, of course, the key figure herself, Jamila Bouhired. After a short welcome, everyone stood while the Lebanese and Algerian national anthems were played.

During the evening the Palestinian poet Samim al-Qasim, the Lebanese poet Ghassan Matar, and the Lebanese singer Julia Boutros and many more—all of whom have a long history of commitment to the fight against Israeli occupation—celebrated Bouhired as an anti-colonial resistance fighter. Arab and international women’s rights activists also highlighted Bouhired’s contribution to the ongoing fight for women’s rights, and stressed her importance as a role model for women around the world.[8] At the end, first Aleida Guevara and then Ghassan bin Jeddo paid tribute to Bouhired, and thus added the necessary official stamp to the iconization. Ghassan bin Jeddo as the official Al Mayadeen representative, initiator of the event and obviously a great admirer of Bouhired. Aleida Guevara as the guest of honour and her qualities, as a politically and socially engaged woman from what Al Mayadeen would refer to at the revolutionary global South promoting her father’s legacy and spirit of resistance, made her the perfect figure to spread international female stardust on the event. Her own reputation as being an outspoken supporter of the Palestinian cause only added to her suitability.

Over the course of the evening, Bouhired was honoured by the participants as a symbol [ramz]; as a symbol of revolution, a symbol of the beautiful time, a symbol of the Arab resistance, a symbol of the struggle, as well as a symbol of the feminist resistance. But Bouhired’s status as a living Arab icon was not only constructed by the invocations of the participants. Also, a broader framing was constructed that placed her within the ranks of internationally celebrated figures. Images of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Nelson Mandela, Ernesto Che Guevara, Yasser Arafat, Hugo Chávez, Ruhollah Khomeini, Mahatma Gandhi, and (of course) Jamila Bouhired herself, reappeared throughout the evening in the shape of posters or cavalcades of photos. Hence, she was presented as belonging to some of the biggest international icons of our time; icons that al-Mayadeen promotes as the revolutionaries, the anti-colonial strugglers, the Third World’s representatives of dignity.

Furthermore, the renowned Lebanese singer Fairouz’s emotional salute to Bouhired, “Letter to Jamila Bouhired” (1959), was used repeatedly as background music. The sound of Fairouz’s characteristic voice is a sound attached with pride and nostalgia. The Lebanese diva represents the legacy of Arab high culture combined with the idea of artistic commitment. Since the 1950s, together with the Rahbani brothers, she has not only played a central role for Lebanese nation building but also for the Palestinian resistance, and the anti-colonial struggle of Abdel Nasser (Stone 2008: 43–53). When Fairouz sings: Jamila / my friend Jamila / greetings to you wherever you are / in jail, in suffering, wherever you are / greetings to you Jamila from my village, I sing to you, it has a meaning beyond the words. Having a song dedicated by Fairouz is, in itself, a confirmation of one’s status as a symbol and thus playing the song becomes a verification of Al Mayadeen’s iconization of Bouhired.

The event in the UNESCO Palace was not only a celebration of a former female fighter and the revolution of a million martyrs, it was equally a nostalgic celebration of a bygone era, of ‘the golden age’. Through images, songs, and global icons and through the selection of artists and activists participating in the celebration, the time of Bouhired was reawakened—if only for a short moment. It was a glorification of the past as a time of heroism, order, and Arab solidarity. That era was at the same time depicted as lost and as necessary to reawaken.

In his speech to Bouhired, Ghassan bin Jeddo argued that opposite contemporary time, the time of Bouhired was a time without delusion, maliciousness, and confusion. He elaborated: The Algerian revolution formed a model for wars of liberation and independence without any confusion. This is a revolution which not only united Algeria and its people but also united the umma and its masses. Nasser’s great Egypt and Egypt’s great people shared money and weapons with the Algerian people. That time is different than the [present] time of foulness (...) (the UNESCO show). For bin Jeddo, it is possible to read the past as a time of clearness, unity, and meaningful revolutions, and thus an obvious example of ‘history without guilt’[9] as Michael Kammen defines the concept of nostalgia. Evidently, the past is much more complicated than the idealized black and white image. If bin Jeddo had only turned his attention towards Yemen in those same years as he was describing, he would have found a bloody war (1962-1970), dividing not only Yemen but the whole region, with Egypt and Abdel Nasser on the one side, facing Jordan and Saudi Arabia on the other—just to mention one example.

This nostalgic and highly selective reading of the past bears resemblance to what Esra Özyürek investigates in her thought-provoking book, Nostalgia for the Modern: State Secularism and Everyday Politics in Turkey (2006). Özyürek analyzes how the political struggle between secularists and Islamists in the 1990s in Turkey played out in struggles over how to read the past. She writes: “the representation of the past became an arena for struggle over political legitimacy and domination. (…) nostalgia can become a political battleground for people with conflicting interests (…) by creating alternative representations of an already glorified past, they [marginalized groups] can make a claim for themselves in the present.” (Özyürek 2006: 154) For the secularists, the longing for a Kemalist modernity created a nostalgic take on modernity. The same longing for the modernity of the past is ever present at Al Mayadeen and through the iconized Bouhired, the station now has an icon that can refer back in time and promote a particular discourse of modernity.

Thus, Al Mayadeen uses an idealized and simplified past to problematize the present just as the Turkish secularists did as part of a contemporary political struggle. Furthermore, this exemplifies Sune Haugbølle’s point about how an icon can facilitate a particular reading of the past. Bin Jeddo and Al Mayadeen use the icon Bouhired to read the past as a time where the fight against colonialism was cleaner, Arab solidarity stronger, and the world less confusing, and not like today’s time of foulness, as bin Jeddo put it. As will become clear in the following section, Hezbollah is given the role as the resistance movement that can carry on the legacy of Bouhired and that fights “the wars of liberation without confusion.”

During the promotional broadcasts and through the evening at the UNESCO Palace, al-Mayadeen re-created Bouhired as a contemporary icon of the armed resistance against imperialism, and of a certain era in history. Al Mayadeen created a conducive setting by repeatedly evoking global icons and capitalizing on the presence of Arab celebrities. Furthermore, emotional moments were created by the use of music with important nostalgic and emotional attachments. But in order to turn a ordinary human from the real world into a powerful secular icon, it needs to be recognized by the public. Thus, the public show at the UNESCO Palace was of central importance and functioned as an act of legitimation. Here, a public celebration of Bouhired could take place, turning her into a true living icon.

In the section below, I turn to the part of the celebration that was organised by Hezbollah in Mlita, and investigate how Al Mayadeen connects the nostalgic past to the present political situation. Furthermore, I discuss how the changing meaning of an icon can create confusion and frustration for the reader.

Changing readings of an icon - Connecting the past to the present

But when I Googled Jamila’s name again and found a photograph of her with Bashar Al Assad, I laughed. Sorry grandpa. Once a heroine, Jamila had become a petrified monument. A guardian of dictatorship.[10]

During the prelude of the show at the UNESCO Palace, the host Kamal Khalaf asked rhetorically: Why Jamila Bouhired? Is it a reawakening of history in order to get some warmth in this cold Arab time and experience nostalgia? Or is it to shake the dust off the current reality in an attempt to re-comprehend the concepts of today and to correct the path by reconsidering consciousness (The UNESCO show, part 1, min 02:12). Khalaf’s questions point to the essential ambiguity of the celebration. Why celebrate a figure from the past that has been forgotten by many and is unknown by new generations? What is the purpose? Below I investigate this question by turning the attention towards the event held on the following day in Hezbollah stronghold, the small village of Mlita. This leads to reflection on the instability and mutability of an icon.

In contrast to the UNESCO Palace, with room for more than 1,000 people, the setting in Mleeta was a small room seating around 50 people. The atmosphere was less glamorous and more intimate than the evening before and the TV viewer was invited into the private sphere of Hezbollah when Nasrallah himself appeared on a big screen and, as ‘the head of the house’, welcomed the crowd from afar. Nasrallah talked about Hezbollah’s struggle, its victories and martyrs, and not least the importance of the resistance. A footage cavalcade of Hezbollah soldiers in action accompanied his words. This opening was followed by speeches by among others Mohammad Raad, the head of the Hezbollah group in the Lebanese parliament and Ghassan bin Jeddo while Aleida Guevara again participated as guest of honour. In Mleeta, Aleida once again played an important role, this time less as a representation of her father’s legacy and more as a contemporary woman whose anti-imperialist struggle had earlier brought her in positive contact with Hizbollah.[11]

While the celebration in the UNESCO Palace had been a celebration of a particular time and a particular set of values all embodied in Bouhired, the ceremony in Mleeta, served to bring Hezbollah centre stage. In other words, the Mleeta event linked the past to the present and provided an answer to Kamal Khalaf’s question of why Bouhired. Unlike the evening before, where Hezbollah had been completely absent, the Mleeta event took the form of a promotional campaign for Hezbollah, where the movement was portrayed as the obvious continuation of the strong and proud legacy of Bouhired, as the true defender of Arab values and interests.

Whereas the picture of Hezbollah as a pan-Arab resistance movement earlier would have been in accordance with a large segment of the Arab public and beyond, by December 2013, Hezbollah’s star status had faded. Hezbollah’s image as the only serious Arab resistance movement had peaked in 2000 when Israel withdrew from the south of Lebanon and again in 2006 during the war in Lebanon, but it had not survived the internal Lebanese political conflict that ended with the movement’s confrontation with its national political opponents in the streets of Beirut in 2008. More importantly, Hezbollah’s military support of Bashar Al Assad in Syria had further weakened its pan-Arab appeal and firmly placed it within the ongoing political and sectarian power struggle in the region (Lob 2014). Thus, Al Mayadeen’s linking of Hezbollah to the newly iconized Bouhired was an attempt to re-establish Hezbollah within the tradition of Arab resistance against foreign occupation as well as within a global struggle against Western imperialism. By bringing back the past on the first evening and then on the following day bringing together the icon of Bouhired and Hezbollah, Al Mayadeen confirmed that Hezbollah is the continuation of the leftist resistance legacy and a movement that secular Arab resistance segments can safely identify with.

Through the events in the UNESCO Palace and in Mleeta, Al Mayadeen not only celebrated Bouhired but also reinvented her as an icon, thus attempting to monopolize the reading of a shared Arab—and international—symbol. After two days of celebration, Bouhired was no longer the empty shell that could be filled with several parallel meanings; she was now an icon of Al Mayadeen’s reading of the past, present, and future. Moreover, Bouhired’s own participation underlined the monopolization and confirmed Al Mayadeen’s translation of her legacy into present times.

In 1962, at the height of Bouhired’s popularity, she travelled to Egypt in order to meet Gamal Abdel Nasser. It seemed a natural culmination of her political activities and a recognition of her commitment for the cause by a leading figure and ultimate icon of the Arab anti-colonial movement. Nasser must equally have enjoyed welcoming the female fighter who in many ways embodied his political slogans. Photos of the young Bouhired together with the fatherly Nasser were circulated, documenting the meeting of two symbols of the same time and the same ideals.

In 2009, Bouhired had already indicated her positioning in contemporary politics when she travelled to Damascus to meet Bashar Al Assad and to receive the Syrian Order of Merit of Excellent Degree. While linkages to Al Assad were already controversial in 2009, by the end of 2013, it had become fatal. Until the uprisings reached Syria, Al Assad had, to some extent, managed to remain a symbol of Arab (secular) resistance by safeguarding the image of Syria as the last Arab bastion facing Israel. Given this narrative, Bouhired’s travel to Damascus in 2009 could still be seen as in line with her legacy and travel to Nasser’s Egypt in 1962. In 2013, on the other hand, when Bouhired was celebrated in Beirut and Mleeta, her choice of political and ideological direction was obvious, and as the quotation in the beginning of this section illustrates, not all readers could conciliate with what the newly iconized Bouhired had come to symbolize.

Al Mayadeen’s iconization of Bouhired exposes the instability of symbols and shows how this instability potentially creates discrepancy between the symbol and the readers of the symbol. The fact that the former revolutionary female fighter had chosen to stand with the established power in Syria, against a public uprising, is for some readers too profound an inconsistency to be bridged. Bouhired becomes a demonstration of why Al Mayadeen disqualifies the current uprisings as real resistance, just as she comes to function as a link between the historical leftist secular values and the contemporary resistance of Hezbollah. Bouhired equally becomes an embodiment of how the revolutionary, progressive, socialist, anti-colonial struggles in the Arab world turned into authoritarian rule; a dilemma which the (Arab) Left has been facing for decades, and which has only become even more acute since the uprisings in 2011 challenged the previous political and ideological positions. Thus, the female embodiment of revolution and modernity now reappeared as an object of worship for what seemed to be the remnants of the secular, anticolonial project of the 1950s—or what David Scott refers to as a “postcolonial nightmare”[12] (Scott 2004).

In 2013, in a divided Arab world, being celebrated at Al Mayadeen was not a neutral act; rather it spoke directly to the division of pro/anti-Arab uprisings, the Iranian-Saudi Arabian power struggle, the war in Syria, etc. and thus potentially challenges the legacy of Bouhired. As the quotation in the beginning of the article illustrates, the connection to Bashar Al Assad alone exposed not only the potential discrepancy between Bouhired’s life and legacy but also between how Bouhired translates her own ideals into contemporary time and how some of her readers would like to see it translated. In 2013, the division of the Arab public was so fundamental that Bouhired’s participation in Al Mayadeen’s events at the same time re-establishes her status as an icon and monopolizes how to read this revitalized icon. The Mleeta event only consolidated Bouhired’s position in contemporary politics.

In this article, I have investigated how secular icons can take form, develop, and not least become an important political tool in a mediatized world. I have analyzed Al Mayadeen’s celebration of Jamila Bouhired as an example of how an orchestrated public event functions as an iconization and how Al Mayadeen’s monopolisation of the forgotten symbol potentially created discrepancy between the icon and the reader of the icon.

By choosing Bouhired, an almost forgotten icon from the past, as the object of celebration, Al Mayadeen ‘recharged’ a symbol detached from contemporary political affiliations but with important nostalgic qualities - an almost empty shell, ready to be refilled. As she stood on the stage in the UNESCO Palace, old, fragile, and at the same time steadfast and committed, she appeared as the pure symbol of resistance raised above contemporary political power games and worthy of iconization. The public celebration orchestrated by Al Mayadeen was not only entertainment but (also) a necessary component for the creation of an icon. By placing her within the prominent company of Nelson Mandela, Che Guevara, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Yasser Arafat, replaying Fairouz’s tribute from the past, having a figure like Aleida Guevara saluting her, and having engaged a gallery of well-known figures from the Arab world to participate in the celebration, Al Mayadeen created an icon. They created an icon that could facilitate a nostalgic reading of the past that highlights the anti-colonial struggle and the progressive leftist ideology just as the icon allowed for a particular translation of this into present time.

During the iconization of Bouhired, Al Mayadeen was strategically trying to awaken nostalgic feelings—longings for a particular identity—of the viewer. It is equally clear that the station had strong ambitions to prove Bouhired relevant as a contemporary icon who could serve as a guide and as a benchmark for true Arab values in what bin Jeddo characterizes as, a time of confusion. Thus, I investigate the iconization as an example of how political fights play out in a symbolic world where images, music, monuments, and secular icons, play the central roles. When re-established as an icon, Al Mayadeen could use Bouhired in the contest over the symbolic world and the management of meanings.

Furthermore, the celebration was strategically used to link Hezbollah’s military activities to Algeria’s war of liberation and thus to revitalize the image of Hezbollah and re-establish the movement within the legacy of Arab resistance movements. As Nasrallah was no longer the global icon that could endorse Bouhired the opposite was at play. After the iconization, Bouhired was the one who could elevate Hezbollah and confirm that the movement represented true resistance. When the newly iconized Bouhired participated in the ceremony in Mleeta, she verified the resistance qualities of Hezbollah and confirmed that the organization carry on her legacies. Thus, it seems that the whole event was not only a celebration of Bouhired, but also—and just as importantly—a revitalization of Hezbollah. Bouhired had become an icon that could facilitate a reading of the past that proved Hezbollah relevant today.

[1] Translations of empirical material are my own.

[2] E.g.: Iran’s Arabic satellite station, Al Alam; Hizbollah’s TV station, Al Manar; Hamas’s TV station, Al Aqsa, Palestinian Islamic Jihad’s TV station, Palestine Al Youm; Nabih Berri’s TV station, NBN; alongside several Bahraini and Yemeni oppositional media (Crone 2017, 69-71).

[3] In Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, Al Mayadeen is a serious competitor to both Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya (Crone 2017, 74-76).

[4] An example of the leftist environment is "www.internatinlsocialist.org.uk." Here, Bouhired appears in a series on Women on the Left and is referred to as a “fighter for Algerian Independence and the liberation of women”; http://internationalsocialist.org.uk/index.php/2013/02/women-on-the-left-djamila-bouhired/#sthash.YJCFpbE1.dpuf.

An example of the feminist representation is found on: www.agirlsguidetotakingovertheworld.co.uk, here she is posted under the title ‘Revolutionary Women’; http://www.agirlsguidetotakingovertheworld.co.uk/#!djamila-bouhired/ccbh.

[5] https://www.marxists.org/history/algeria/2009/djamila.htm.

[6] These spots are no longer available online after the homepage www.djamila-bouhired.com was closed in 2016.

[7] The first usually only used in secular contexts whereas the later has stronger Islamic sentiments.

[8] E.g. the former president of the Committee of the Rights of Lebanese Women, Linda Mattar, and the general secretary of the National Federation of Indian Women, Annie Raja.

[9] Cited by Boym (Boym 2001, xiv) from Michael Kammen: Mystic Chords of Memory, 1991, p. 688.

[10] Quotation from the art performance Have you ever killed a bear? Or becoming Jamila (2013) by the Lebanese artist and activist Marwa Arsanios. The performance revolves around the story of Bouhired and the ethical dilemmas connected to her acts as a fighter in the past (is it terrorism?) and to her political stance today (is she being loyal to her own legacy?). In the performance, a young girl, fascinated by the story of Bouhired, unexpectedly gets the opportunity to play the role of her, but gets confused when she discovers that Bouhired’s contemporary reputation is not what she expected… “Once a heroine, Jamila had become a petrified monument. A guardian of dictatorship” the young girl notes. Arsanios investigates the disappointment over Bouhired’s changing representation and the potential conflict of these changes.

[11] Aleida Guevara met with Hezbollah officials during her visit to Lebanon in 2010, see: http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2010/guevara301010.html.

[12] In his book Conscripts of Modernity: the tragedy of colonial enlightenment (Scott 2004), Scott attempts to form a new form of postcolonial criticism “after the collapse of the social and political hopes that went into the anticolonial imagining” becomes evident and the bankruptcy of the postcolonial regimes palpable (Scott 2004, 1).

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub