Issue 31, winter/spring 2021

https://doi.org/10.70090/HN21USMP

Abstract

Many highly regarded medical doctors have developed guidelines to promote themselves professionally when connecting with their patients through social media sites (Sullivan 2018). However, many still use these platforms for marketing rather than disseminating appropriate medical information. This paper surveyed a sample of medical doctors in Iraq, and it aimed to analyze the motivations behind their use of social media to communicate with their patients. Follow-up interviews were organized at eight medical locations in Iraq, where the doctors were interviewed to gain additional data. Social media offers doctors the ability to enhance their relationships and improve their marketing, and this study identified high overall social media usage among doctors in Iraq (with 79% male doctors and 21% female doctors using social media). The participants’ listed specialties were as follows: 8% dentists, 10% internists, 20% general surgeons, 12% urologists, 4% cancer doctors, 9% OB-GYN, 4% family specialists, 9% pediatricians, 5% dermatologists, 2% ophthalmologists, 3% rheumatologists, and smaller percentages of anesthesiologists, radiologists, and orthopedists. Years of experience also proved to influence social media use, with less experienced doctors using it more often.

Introduction

Social media networks are no longer limited to their traditional roles. They have become virtual platforms for exchanging medical information, and they have contributed to moving the medical profession from behind closed doors into the online electronic environment (Rovniak and Kraschnewski 2013). From there, doctors can play significant roles in spreading health awareness. However, many misuse these platforms by distributing misleading information and promoting improper medical guidance (George, Rovniak, and Kraschnewski 2013). This study examines how doctors communicate with patients through social media. Patients were found likely to engage in various types of online health activities, such as using social media sites to study medical questions, search for answers, and seek health information (J Med Internet Res. 2017). This study’s results highlighted the critical role of doctor-patient communication and emphasized the importance for doctors in Iraq to turn to social media networks for health purposes.

This study categorized doctors who use social media networks into two types. The first uses social media to serve the community, while the second views social media as a means to market their practice by discussing promotions and sharing advertisements. Medical contact through social networking has become one of the most critical issues to consider when attempting to understand how doctors use social media platforms and how patients receive their messages. For those reasons, scholarly research has begun to emphasize the importance of social network usage among doctors. In the medical context, the main disadvantage presented by social media networks is that they are not usually run by doctors, and instead are operated by people outside the profession who have no connection to the medical field.

This research is meant to unpack a broader question: What is social media’s role in the medical field? This question is especially critical because many influential doctors are now active on social media. This study organized a representative sample consisting of 222 Iraqi doctors in Baghdad. Phone interviews were set up, during which the doctors completed questionnaires designed to explain the roles and effects of the social media sources they used to connect with their patients.

Literature Review

The purpose of this research was to investigate communication strategies used on social networks by doctors with patients in Iraq, including the doctors’ motives for adopting these strategies. The advantage of using social media is its dynamic ability to disseminate health information, but its use also has disadvantages, such as inefficiency and the unreliability of information (Shuaa, Bajnaid, Elyas, and Alnawasrah 2017). Previous research has predominantly found that people engage with social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram to satisfy particular social needs (Azer 2017). There is a consensus among scholars that social media enables users to engage in shallow relationships and to reaffirm pre-existing, healthy relationships (Lauren, Evans, Pumper, and Moreno 2016).

Jiang and Liu (2020) created an online survey to examine the relationship between Internet health information seeking (IHIS) and patient-centered communication (PCC) in China. The driving force behind this study, an uptick in violence orchestrated against Chinese healthcare practitioners, led the researchers to assume that negative publicity about China’s healthcare system was causing friction between doctors and caregivers. In response to increased violence against healthcare practitioners, medical professionals have encouraged patients to engage in medical communication, PCC, and IHIS, which lead to greater responsiveness and transparency among doctors and patients. The researchers hypothesized that one-way IHIS is positively associated with patient-centered care. The researchers created a convenience sample through an online survey company and recruited 483 people to complete the survey in exchange for 10 Chinese Yuan. The researchers operationalized IHIS as the frequency of using the Internet to search for health information unidirectionally, without communicating with others online. The study found that one-way IHIS was not associated with patient-centered care, because people are overwhelmed by the amount of health-related information found on the Internet.

Zheng (2014) conducted interviews with 32 young adults in 2012 to understand why young people seek health-related information on Facebook. The study assumed that social networking facilitates transparent interactions between social media users and public health practitioners. The researcher posed three separate questions to identify how young adults use social media for health information purposes. The research questions were as follows: First, how and why do young adults seek and scan for online health information? Second, how and why do young adults usually use Facebook? Third, why do young adults seek and scan for health information on Facebook? Zheng recruited 32 Facebook users between the ages of 18 and 30 and used a maximum variation sampling strategy to place information in code categories. The study found that young people often used open-source health information to make self-diagnoses. Respondents generally did not pay careful attention to all news feeds and instead paid selective attention to a few posts or photos. Finally, this study found that health information acquired from Facebook was limited.

Ben-Yakov, Kayssi, Bernardo, Hicks, and Devon (2020) surveyed a pool of healthcare professionals to determine how frequently they use Facebook and Google to search for their patients. The primary assumption was that looking up a patient potentially breaches the ethical obligations of healthcare practitioners. The researchers distributed the survey to 683 staff doctors, 116 residents, and 54 medical students through the Canadian Association of Emergency Doctors, as well as 226 fourth-year medical students at the University of Toronto. The survey found that of 530 individuals who responded, about 12% used Google to search for patients, and roughly 2% performed Facebook searches on their patients. Moreover, 29% of respondents confirmed that looking up a patient on a search engine or social media is “very unethical.” Twenty-one percent labeled the practice as “unethical,” and only 9% believed that the behavior was “ethical.”

Methodology

In contrast, others give importance to the fact that the sender initiates the process, and thus the sender needs the communication the most. Relationships vary depending on the situation and the place where the need to communicate arises (Sabee, Bylund, Weber, and Sonet 2012). However, all these models narrow down to a simple communication model, with the sender conveying information to the receiver (Foulger 2004).

Lasswell's communication model is used as an umbrella when referencing his commonly quoted "Who said what, in which channel, to whom, and with what effect?" ( Sapienza, Iyer, and Veenstra 2015). This study's questionnaires were designed based on Lasswell's communication model between doctors and patients, with social media as the medium, and focused on those working in Iraq. It assembled a field team to conduct phone interviews to investigate social media usage among 222 doctors. This survey is designed to understand the relationship between patients and doctors through the lens of social media and to determine which social media platform is the most widely used.

The most important aspects of the survey are identifying and selecting the potential sample, contacting doctors, collecting data from them during COVID -19 given its challenges to delivering healthcare, evaluating and testing questions, and selecting the mode in which questions are asked and responses collected. Three stages were involved to complete the survey in the given timeline and circumstances.

Instrument design:

The draft instrument is designed based on the uses and gratification motives and a few previous studies on physicians' use of social media, taking into consideration the Iraqi context (Park and Goering 2016).

Pretest:

The draft instrument was presented to ten doctors (five male and five female) to get their feedback. The other studies that the author used are: Alsughayr AR. (2015), social media in healthcare: Uses, risks, and barriers. Saudi J Med Sci. George, D. R., Rovniak, L. S., & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2013). Dangers and opportunities for social media in medicine. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. Ventola C. L. (2014). Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P & T: a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management.

Face-to-face preparing frame:

The researchers visited the clinics to identify the sample of doctors and schedule phone call interviews. The interviewers confirmed that the male gender dominates social networking usage as a tool in doctor-patient relationships. It was also found that social networking does not reflect the male-to-female physicians' ratio in the community. The two researchers prepared a frame of 288 doctors who accepted to conduct the interviews, however only 222 successful interviews were completed in a month of phone interviews. Moreover, most female doctors refused interviews because they do not use social networks to communicate with patients for ethical and cultural reasons. Another indication of the pretest is that female doctors lean more towards working in public hospitals instead of private clinics for security reasons.

Sampling:

Geographically, we selected a random sample of doctors in Baghdad's four major medical areas, which serve one-fourth of all residents of Iraq. Accordingly, four of the area's most critical medical locations were designated as sites to select appropriate clinics for the research. It included mostly private clinics (Al-Harithiya - Al-Kindi St, Palestine St - Beirut Square, and - Al Sadoon St - Al-Nasr Square and Kadhimiya - 60. St). The sample is considered random, starting in the sample seeds of Iraqi doctors (men and women). In cases where a doctor refused to interview, the interviewer moved on to the next clinic. Ultimately, the sample was composed of 79% men and 21% women. And specialties were as follows: 8% dentists, 10% internists, 20% general surgeons, 12% urologists, 4 oncologists, 9% OB-GYNs, 4% family specialists, 9% pediatricians, 5% dermatologists, 2% ophthalmologists, 3% rheumatologists, and smaller percentages of anesthesiologists, radiologists, and orthopedists.

We then categorized the sample by years of experience in the medical field, as follows:

- 17% with up to 20 years of experience

- 16% with up to 15 years of experience

- 37% with 5 to 15 years of experience

- 30% with 3 to 4 years of experience

The respondents fell into the following age categories: 49% between 36 and 45 years of age, 17% between 31 and 35, and 5% between 25 and 30 years. We chose doctors as seeds for our random sample from each clinic, resulting in around 20 to 25 interviews at each of the ten final participating facilities. However, some interviews were canceled due to refusals or because the doctors were unavailable. Canceled interviews were replaced with other interviews so that 20 to 25 interviews were ultimately conducted at each medical center (for a total of 222 successful interviews). The phone interviews period lasted approximately one month; the field study began on February 15, 2020 and ended on March 18, 2020. Twenty-nine percent of female doctors rejected the interviews because they did not use social media to communicate with patients.

The phone interviews:

Three researchers (one male and two female) conducted phone interviews, and the number of daily interviews for each researcher was from two to five.

Research Questions

A questionnaire was developed based on doctors’ and patients’ needs through social media networks (Longnecker 2016) and the uses and gratification theory (Scherer 2010). It included the following areas of inquiry: identifying how doctors in Iraq use social media, the rate at which they are exposed to social media (how many hours they spend using it), how many times each day they use social media platforms, how many websites they visit, and the objectives behind their usage. The questionnaire also covered issues affecting individuals who use social media networks for medical or other purposes, the benefits of using social media for medical purposes, and the risks presented to patients who use social media. Other topics included the advantages and disadvantages of social media networks and the motives of patients who resort to these platforms when seeking medical advice. Data were collected during a field survey, including face-to-face interviews with doctors, as well as through phone interviews. Each interview lasted no longer than 8 to 12 minutes. The interviews were conducted based on scheduled times between the interviewers and doctors.

The research questions can be summarized as follows:

- How much time do doctors spend on social media for medical purposes?

- What are the specializations of doctors who use social media for medical purposes?

- What social media sites do doctors use for medical purposes?

- What motivates the use of social media by doctors and patients for medical purposes?

- What are the risks of using social media for medical purposes?

- What are the disadvantages of using social media for medical purposes?

Obstacles and Limitations

While conducting this study, the most significant obstacle was persuading physicians to participate. There was also difficulty in setting appointments to call physicians, due to their busy schedules. Some physicians rescheduled their appointments many times, resulting in extended time spent by the researcher rearranging appointments. Many physicians inquired about the entity behind this research and asked whether personal information would be required. In response to these questions, the survey study confirmed that all research was solely conducted and circulated by the author, and that no personal information would be required. Many physicians refused to participate but did not specify their reasons for doing so.

Results

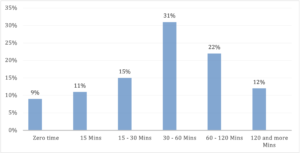

When questioned about how much time the doctors spent on social media for medical purposes, the results showed that 9% did not use social media for medical purposes, and 11% of the doctors used social media for zero to 15 minutes daily. Fifteen percent did so for 15 to 30 minutes per day, 31% did so for 30 to 60 minutes per day, while 22% did so for 60 to 120 minutes per day. Twelve percent of the participants spent 120 minutes or more per day using social media for medical purposes (Figure 1).

Figure 1, Daily time doctors spend on social media for medical purposes.

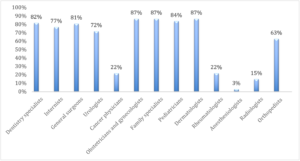

Figure 2 shows the breakdown of social media use by specialist type. The research revealed that social media is used for medical purposes by dentistry specialists (82%), internists (77%), general surgeons (81%), urologists (72%), oncologists (22%), obstetricians and gynecologists (87%), family specialists (87%), pediatricians (84%), dermatologists (87%), rheumatologists (22%), anesthesiologists (3%), radiologists (15%), and orthopedists (63%). The doctors confirmed that more than 80% of the patients they interacted with via social media are underage the age of 40, and they use social media to interact with very few patients older than 45. Women represented more than 75% to 80% of the patients they contact using social media.

Figure 2, Social media usage among doctors by specialty.

The survey results showed that participants used a variety of social media networks. The highest percentage of participants used Facebook (93%), followed by YouTube (73%), WhatsApp (57%), Instagram (43%), Twitter (39%), Viber (20%), Snapchat (14%), LinkedIn (13%), and Telegram (6%). The results also showed that participants used social media sources for a variety of purposes. Only 5% did so solely for medical purposes, while 12% did so solely for personal purposes, and 83% did so for both medical and personal purposes.

In addition, the chart concludes that social media usage ranges from the lowest of 3% (anesthesiologists) and to the highest of 87% (obstetricians and gynecologists, family specialists, and Dermatologists). Moreover, we can see a steady flow between obstetricians and gynecologists, family specialists, dermatologists, and urologists as there is a minor 15% difference between the specialties. Furthermore, there is another steady flow between cancer physicians and radiologists, while anesthesiologists and orthopedists were found to be outliers as they do not share a similar percentage with any other specialty.

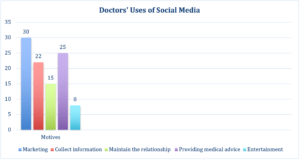

Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the doctors’ social media uses. Thirty percent used it for marketing, 22% for collecting medical information, 15% for maintaining relationships with patients, 25% for providing medical advice to the public, and 8% for entertainment.

Figure 3, How doctors use social media

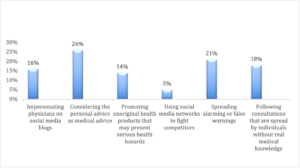

Figure 4 shows respondents’ opinions about the risks of patients using social media for medical purposes. As shown, 16% warned against those who impersonate doctors in health-related groups, and 26% warned against considering advice based on personal experiences as legitimate medical information. Fourteen percent warned against the promotion of counterfeit or adulterated health products that may result in serious hazards to patient health, 5% warned against those who use social media to attack competitors, 21% warned against the spread of alarming and false warnings, and 18% warned against the large amount of information spread by people without proper or sufficient medical knowledge.

Figure 4, Perception of Risks to Patients Using Social Media for Medical Purposes .

The survey results showed that 73% of participants operated their social media accounts, while 11% had others operate their accounts for them. Sixteen percent indicated that they did both (that is, they received assistance only sometimes). When asked whether they had success in establishing personal relationships with their patients via social networks, 22% of participants answered “yes,” while 78% answered “no.” Overall, 77% considered social media networks useful in the medical field, while 23% did not.

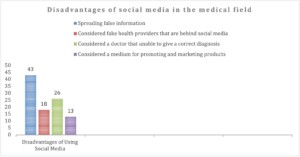

The results showed that 85% of participants perceived disadvantages to using social media networks in the medical field, while only 15% said the practice had no disadvantages. Figure 5 shows the reasons that some believed there were disadvantages. Forty-three percent considered social media a medium for spreading false information, 18% expressed concerns about fake health providers on social media, 26% stated that a doctor is unable to give a correct diagnosis through social media, and 13% of doctors considered social media as a medium for promoting and marketing products that spread rapidly. Likewise, social networks were considered as not a safe way for a medical consult.

Figure 5, Disadvantages of using social media in the medical field.

The study results showed that patients resorted to social media for medical advice for several reasons, including to get a variety of consultations from several doctors in an easy and efficient way (29%); to maintain relationships with doctors (33%); to contact a doctor anonymously (28%), and to take advantage of free consultations (10%).

Discussion

The emerging use of medical consultation in Iraq has propelled the establishment of doctor-patient relationships via social media. Doctor-patient relationships rely on mutual familiarity, trust, and interaction between physicians and patients at the patient’s time of need (Godbole, Koyle, and Duncan 2015). To better understand the utility of social media as a health communication medium, this paper utilizes the uses and gratifications theory to examine the doctors’ motives to build a relationship between them and patients. The research involved analyzing survey results from 222 participants who reported using social media for health-related reasons, and 33 that said they did not use social media for these purposes, which were considered outside the abovementioned participants.

The study found that most participants used three different networks, with Facebook as the most widely used (93%), to communicate with their patients. Facebook’s popularity was followed by WhatsApp (57%) and Instagram (43%). Most participants used social media networks for both personal and medical purposes. Most participants considered social media networks to have practical usages (77%), while others considered them harmful (23%). These data about doctors’ communication choices reveal new information about doctors’ relationships with patients. Although most of the doctors said it was not effective in building the doctor-patient relationship, there are also significant risks and disadvantages associated with its use.

Social media has a variety of uses for marketing of medical treatment. However, because of the doctor-patient relationship’s importance and seriousness, there is a need for rules and ethics for social media use in the health field, which users must understand. Young people and women are the most likely to use social media for medical inquiries, which is due to a preference to preserve privacy; further studies of this phenomenon should be conducted (Popper-Giveon, Israeli, and Keshet 2019). Social media and other communication technology tools can build relationships between doctors and patients and empower patients to make safer and healthier decisions.

However, there are disadvantages to using social media in the medical field, primarily through the exploitation of patients by those who falsify their backgrounds and take the roles of doctors for profit. In this study, uses and gratifications theory suggests that doctors and patients are active and motivated to select social media as a site to consult and build relationships. The greater control and choice allowed by new social media has opened up new avenues for uses and gratifications research, and this has led to the discovery of new gratifications, especially those related to social media (Kirchherr and Charles, 2018). By applying uses and gratification theory to the survey results, the research derives the following conclusions:

- Social media use is goal-oriented. Doctors are motivated to use social media because it is an avenue for patients and doctors to achieve their goals. Thus, Figure 3 shows a breakdown of doctors’ motives for their social media usage.

- Doctors and patients select Facebook and WhatsApp as their preferred platforms based on the expectation that these will satisfy the specific needs of their patients.

- Despite the patients’ needs and the doctors’ desires to use social media, which are both grounded in the two parties’ respective motives, this mode of communication comes with risks. Specifically, the doctor-patient relationship faces risks related to the medical advice provided by the doctor or their representative over social media. This study showed that the risks of using social media in the medical field include the posting of false information or fake medical advice.

Motivations for Using Social Media by Doctors

The study has revealed four motivations for social media usage by doctors, including diversion, personal relationships, personal identity, and surveillance (Rubin, 2009):

Diversion: (A form of escaping from the pressures of every day). Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the doctor's diversity of uses for their social media, such as for entertainment.

Personal Relationship: (Where the viewer gains companionship, either with the medium itself or through conversations with others about media). Figure 3 shows that maintaining relationships are one of the primary motives of doctors for using social media.

Personal Identity: (Where the viewer can compare their lives with characters and situations on social media, and explore, reaffirm, or question their identity. The paper refers to all the sample individuals who had a pure functional identity, which is that he/she is a doctor. Moreover, there was a sub-functional identity (the doctor's specialty). Ultimately, the study found that their medical and specialized identity distinguished the doctors' use of social media.

Surveillance: (Where the media are looked upon for a supply of information about what is happening in the world). In addition, Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the doctors' motives for their social media usage. In this case, 22% used social media for collecting medical information.

Lastly, the uses and gratifications theory was employed to understand the nature of virtual communities' use of one of the aspects of new media, namely social networks (Quan-Haase, Anabel and Young, Alyson 2010). Furthermore, the theory is applied to understand the behaviors of individuals who use these sites (Roy, Sanjit 2009). The significant indication of doctors' behavior based on this theory is that male doctors are the most likely to use social media. It was also found that there are fears among female doctors to use it. The research likewise uncovered the gratifications sought and obtained by doctors and patients through social media use. Examining their behavior uncovered five needs motivating their participation in Facebook in particular, which was the most widely used platform. Those needs included marketing by staying in touch with patients, entertainment through Facebook for amusement or leisure, maintaining relationships, seeking information, and finally, providing medical advice. At the same time, a different study found that Facebook users gratified their need for connection through the social network (Raquel, Crandall, and Ferradaz 2019). Increased usage, both in the amount of time one had been active on Facebook and in the number of hours per week one spends using Facebook, increased the gratification of this need.

References

Aljasir, Shuaa, Ayman Bajnaid, Tariq Elyas, and Mustafa Alnawasrah. 2017. “Users’ Behavior on Facebook: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Business Administration 8, no. 7: 111-129. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v8n7p111

Alsughayr AR. 2015. Social media in healthcare: Uses, risks, and barriers. Saudi J Med Sci 3:105-11. https://www.sjmms.net/text.asp?2015/3/2/105/156405

Azer, Samy A. 2017. “Social Media Channels in Health Care Research and Rising Ethical Issues.” AMA Journal of Ethics 19, no. 11: 1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.11.peer1-1711

Ben-Yakov, Maxim, Ahmed Kayssi, Jennifer D. Bernardo, Christopher M. Hicks, and Karen Devon. 2020. “Do Emergency Doctors and Medical Students Find It Unethical to ‘Look up’ Their Patients on Facebook or Google?” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 16, no. 2: 234-239. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2015.1.24258

Campbell, Lauren, Yolanda Evans, Megan Pumper, and Megan A. Moreno. 2016. “Social Media Use by Doctors: A Qualitative Study of the New Frontier of Medicine.” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 16: 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y.

Foulger, Davis. 2004. “An Ecological Model of the Communication Process.” Accessed May 2, 2021. http://davis.foulger.info/papers/ecologicalModelOfCommunication.htm#:~:text=In%20the%20ecological%20model%20%2C%20the,effects%20are%20found%20in%20various

George, Daniel R., Liza S. Rovniak, and Jennifer L. Kraschnewski. 2013. “Dangers and Opportunities for Social Media in Medicine.” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology Journal 56, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0b013e318297dc38

Godbole, Prasad P., Martin A. Koyle, and Wilcox T. Duncan. 2015. Pediatric Urology: Surgical Complications and Management. Hoboken: Wiley Publishing.

Jiang, Shaohai, and Jiaying Liu. 2020. “Examining the Relationship Between Internet Health Information Seeking and Patient-Centered Communication in China: Taking into Account Self-Efficacy in Medical Decision-Making.” Chinese Journal of Communication 13, no. 4: 407-424. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2020.1769700

Kirchherr, Julian, and Katrina Charles. 2018. “Enhancing the Sample Diversity of Snowball Samples: Recommendations from a Research Project on Anti-dam Movements in Southeast Asia.” PLoS ONE 13, no. 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201710

Littlejohn, Stephen W. and Karen A. Foss, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of Communication Theory. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

Longnecker, N. 2016. “An Integrated Model of Science Communication — More than Providing Evidence.” Journal of Science Communication 15, no. 5. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.15050401

Park, Daniel Y. & Elizabeth M. Goering. 2016. “The Health-Related Uses and Gratifications of YouTube: Motive, Cognitive Involvement, Online Activity, and Sense of Empowerment.” Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet, 20: 1-2, 57, DOI: 10.1080/15398285.2016.1167580.

Popper-Giveon, Ariela, Tamar Israeli and Yael Keshet. 2019. “Post-trauma: healthcare practitioners use social media during times of political tension.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 36, no. 2: 189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2018.1536296.

Quan-Haase, Anabel & Young, Alyson. 2010. Uses and Gratifications of Social Media: A Comparison of Facebook and Instant Messaging. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 30. 322. 10.1177/0270467610380009.

Roy, Sanjit. 2009. Internet uses and gratifications: A survey in the Indian context. Computers in Human Behavior. 25. 855. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.

Rubin, A.M 2009, Use and gratifications perspective on media effects. In J.Bryant, and M.B. Oliver (Eds), Media effects: Advances in theory and research 3rd ed., Routledge.

Sabee, Christina M., Carma L. Bylund, Jennifer Gueguen Weber, and Ellen Sonet. 2012. “The Association of Patients’ Primary Interaction Goals with Attributions for their Doctors’ Responses in Conversations about Online Health Research.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 40, no. 3, 288.

Sapienza, Zachary S. Narayanan Iyer & Aaron S. Veenstra. 2015. “Reading Lasswell's Model of Communication Backward: Three Scholarly Misconceptions.” Mass Communication and Society, 18:5, 599-622, DOI: 10.1080/15205436.2015.1063666

Sullivan, Thomas. 2018. Federation of State Medical Boards Model Policy Guidelines for social media, Policy & Medicine.

Tan, S. S., & Goonawardene, N. 2017. “Internet Health Information Seeking and the Patient-Physician Relationship: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19 (1), e9. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5729

Ventola C. L. 2014. “Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices.” P & T: a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 39(7), 421-456.

Weston, Raquel, Marie Crandall, and Paula Ferrada. 2019. “Social Media and Free Open Access Medical (FOAM) Education.” Current Surgery Reports 7, no. 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40137-019-0224-2

Zheng, Yue. 2014. “Patterns and Motivations of Young Adults’ Health Information Acquisitions on Facebook.” Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet 18, no. 2: 157-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/15398285.2014.902275

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub