Issue 32, summer/fall 2021

https://doi.org/10.70090/IA21TCRT

The COVID-19 crisis has jeopardized the stability and growth of several sectors, including cultural industries, and has impacted societal relations between people and across countries. In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, we hear little about initiatives or policies pertaining to cultural relations. This paper reviews cultural relations trends throughout the COVID-19 crisis that have demonstrated a shortfall in taking effective initiatives during these challenging times. In this paper, the concept of cultural relations is approached from the perspective of relationships and interactions between individuals and groups of different cultures and across national boundaries. The paper adopts J.M. Mitchell’s (2016) view on international cultural relations as being “dedicated to the task of helping different cultures to understand each other and to learn from each other” (xii). Through micro-illustrations that can help identify some prevalent patterns, I discuss how cultural relations across the MENA region have materialized during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to a lack of international cultural relations initiatives, several MENA countries have adopted a conservative, unilateral and domestic position, compromising the role of culture and undermining the structures supporting cross-cultural relations.

The MENA region has been critically affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. By October 2020, Qatar and Bahrain showed the highest percentage of cases by population, while Oman, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia followed closely with a significant number of cases. The Gulf countries imposed strict confinement procedures right from the start of the pandemic and managed to keep their COVID-19 death rates relatively low. When COVID-19 hit, MENA countries entered a 'sphere of consensus' (Hallin 1986), a homogenized mode of media reporting that legitimizes discourses and calls for citizens to abide by public health recommendations. The dominant narrative called for isolation, curfew enforcement, assuming shared responsibility, and supported precautionary instructions that included washing hands, keeping safe distances, and wearing masks. Typical in times of national crises, local media mobilized to amplify their governments' messaging and shared health organizations' recommendations (Faris 2010; Graham et al. 2015).

While the MENA countries generally resemble one another with regards to their stance on conformist media, the region is not a homogeneous one. Modern Standard Arabic is the official language used across the Arab zone, yet little else unifies the region's countries. MENA countries have diverse and autonomous politics, economies, and socio-cultural apparatuses. However, they also have—or at least attempt to have—various bilateral and multilateral agreements and partnerships that are often proven ineffective. For instance, regional organizations, such as the League of Arab States, the Arab Maghreb Union, and the Gulf Cooperation Council, have proven ineffective in mediating between countries (Pinfari 2009), promoting inter-regional or regional-international interests, or even cooperating during the pandemic. King Mohammed VI of Morocco noted in the 2017 African Union Summit that the Arab Maghreb Union is, for all intents and purposes, dead (Chtatou 2017). This paper will highlight how Arab countries lack collaboration toward sustaining cultural relations. It will also point to the resurgence of nationalist practices across the MENA region, even during the pandemic. First, the discussion starts with three factors that represent challenges to international cultural relations, followed by the opportunities that have arisen during the COVID-19 crisis and those that could still be built upon to revive a conversation about international cultural relations.

Challenges to international cultural relations

The Persistent Digital Gap

The isolation imposed by the lockdowns due to COVID-19 made technology essential for individuals to log in to the world and participate in their communities. Yet, practically, internet connectivity remains a critical issue in MENA on several fronts: low speed, connection quality, lack of skills, high cost, but also control and surveillance.

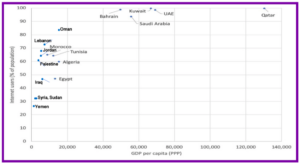

In the below chart (adapted from Internet Society 2020), MENA countries are grouped into three clusters based on their types of connectivity. Gulf countries enjoy the highest Internet penetration rates, close to 100% for many, thanks to their accumulated wealth that has enabled investment in ICT infrastructure and the implementation of smart solutions leading to today's flawless high speed and high-quality connectivity. However, their surveillance and control practices present a limitation on human rights and freedom of expression.

Fig. 1. MENA countries’ Internet penetration rates by GDP per capita (2018). Source: Internet Society (2020), and modified by the author.

In the second cluster, we find countries from the Levant and North Africa where some five to seven people out of 10 have access to the internet. Still, their connectivity is uneven and further challenged by high costs, illiteracy, inexperience, and location (urban vs. rural gaps). The countries in conflict zones that form the third cluster suffer even more due to severely damaged infrastructures and challenges associated with ICT access, adoption, and usage.

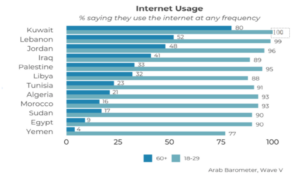

Whatever the region, 2019 data shows that internet usage is highly skewed towards the younger group of 18-29 year-olds, whose access to the internet remains unequaled.

Fig.2. Internet usage in MENA by age group (Source: Arab Barometer)

When examined under the lens of communication for development and social change, 'participation' emerges today—during the pandemic—as a central issue, not for development but everyday occupations (Carpentier 2007). Regardless of age, education, or employment status, online access and connectivity are vital parts of daily life (Huesca 2003). However, participation is also framed by inclusivity and exclusivity.

During this pandemic, it has become evident that participation is a sine qua non for international cultural relations. Participation facilitates belonging to communities, where one carries out social, economic, and educational activities; however, this participation requires access. COVID-19 has only made it more apparent and more pressing: universal access to the internet is a human right necessary for attending to daily needs—cultural ones included (Coleman 2011).

Throughout the region, it is not uncommon to hear stories about university students who live in rural areas and have to walk miles to find a Wi-Fi connection that would enable them to pursue their online courses. For instance, the Omani News company (@oman.news_1, Oct. 11, 2020) shared a story on Instagram of a student from Sultan Qaboos University who lives in a rural area and has to walk 5 km daily to find a public Wi-Fi spot, sitting on a carpet on the ground. Students have been suffering from poor connectivity or none in rural areas for years, and the region’s authorities have given little attention to this urban/rural divide.

Fig. 3. An Omani student using public Wi-Fi on the street (Translation. Abdallah Al-Adawi: This picture shows one of Sultan Qaboos University’s students from Al-Farfar village in Wadi Bani Omar in the governorate of Saham, where he crosses five km daily to find a communication network signal. He lays a carpet on the ground to pursue his remote education, and this is the case of many others in villages and cities in the Sultanate.)

In Tunisia, where I conducted focus groups with rural households (for an ongoing research project on media usage in Tunisia), I was told the Internet is so slow that users have to walk for miles to get close to a spot where they can find a connection. They usually do so through their mobiles using Facebook light, a lighter version of Facebook that enables them to connect at a lower cost and makes heavy downloads more affordable. Those I spoke with expressed how important it is for them to connect to forums and social media with people from other countries—social conversations, entertainment, and cultural content ranking at the top of their usage. This is not exclusive to Tunisians; Payal Arora, in her book The Next Billion Users: Digital Life Beyond the West (2019), found that entertainment dominates the consumption among digital users in low-income countries; entertainment, shopping, and socializing are the first motives for Internet usage by the poor, she finds. Inspired by what they consider the successful stories of their neighbors and friends, several male participants told me during my fieldwork that they use social media and are active on online forums, hoping to build relationships with girls from Europe or elsewhere. This method is seen as an alternative way to plan their immigration and as an escape strategy from a home country they believe has failed them.

Migration during the COVID-19 pandemic

As a cross-national interaction of international cultural relations, migration continues to be a critical challenge. The pandemic has aggravated the conditions of migrants and provoked even more illegal crossings in some places. In Tunisia, for instance, compared to 2019, the number of illegal migrants to Italy has increased fourfold: In July 2020, 4252 Tunisian migrants were intercepted compared to some 500 at the same time in 2019, excluding those, of course, who had landed undetected (The Guardian 2020). The 2020 Arab Youth Survey shows that about one-third of Arab youths are more likely to emigrate due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Asda’a 2020). The majority are from Lebanon (77%), 41% are Algerian, 33% Egyptian and Jordanian, and 9% are Saudis.

Several factors, including lockdowns, the deployment of coercive apparatus in cities to keep citizens at home, and low employment levels, are pushing young men (mainly) to risk their lives for work opportunities abroad. Typically, they use social media platforms to arrange for their illegal crossings. In the case of Tunisia, youth use Facebook and Telegram sites that host fake touristic pages about Italy and, with the contribution of local fishermen who are part of the network who ensure the first part of the trip, they organize their Mediterranean crossing at the cost of about 1200 Euros per person (The Guardian 2020).

Social media has become a proxy for cross-national opportunities, both legal and illegal, defying migration agreements and the limitations of national borders. Due to its high penetration, social media has become extremely popular, with at least nine out of 10 young Arabs using one or more social media platforms daily. Second only to WhatsApp, in 2019, Facebook had at least 80% daily use among the youth in the region (Asda’a 2020).

The ins and outs: The repatriation dilemma

Days after declaring the pandemic started, border control was tightened worldwide, and MENA countries were made to feel like fortresses. The mobility of those crossing borders became highly politicized. Entering, returning, or even staying in a country primarily composed of non-nationals (mainly referring to GCC countries) caused social fragmentation that may have a long-lasting impact. Citizenship became the only marker of belonging, deepening pre-existing inequalities.

In Kuwait, for instance, with resentment, a citizen called for the immediate expulsion of 'guest workers' who were being blamed for spreading the virus (John 2020). Similarly, in Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, non-national laborers were repatriated. Residents were not permitted to bring back immediate family members stuck abroad, although they held valid residency permits, while nationals could do it. In Qatar, salary cuts were applied to expatriate government employees but not citizens (Foxman 2020). In Saudi Arabia, the government pledged to pay 60 % of wages for Saudi nationals working in the private sector, but not to expatriates. These measures have created anxiety and bitterness among expatriates and intensified the social cohesion fracture with regards to the national-resident relationship (Vora & Koch 2015; Mitchell & Allagui 2019). This is despite the state’s attempt to preserve some nationalist and communal narrative by continuing to provide accessible healthcare for all through a shared sense of responsibility to flatten the curve.

In their effort to limit the spread of COVID-19, the GCC governments have taken steps that have deepened and expanded the inequality between citizens and non-citizens, causing profound tensions in cultural relations (Dohanews 2020). With salary cuts and layoffs, Qatar could see an exodus of 10% of its workforce, predicts Oxford Economics (Foxman 2020), leading to failures in its labor migration agreements and sensitivities regarding transnational cultural relationships.

When travel was impossible, intercultural relationships, whether institutionalized or not, have become mediated through social media and telecommunication applications. The fact that bans on VoIP calls, including WhatsApp, Skype, and Houseparty, continue to apply under COVID-19 represents a challenge to maintain intercultural relations. This impedes people’s access to international conversations and cultural exchanges at a time when they need to come together more frequently and more intensely. Increased surveillance and monitoring practices thus continue to present challenges to freedom of expression, and people can face persecution if they criticize how their governments handle the pandemic. As governments continue their surveillance practices, people will also continue using counter-strategies such as VPNs, adapting to the pandemic, and attempting to create new venues to sustain cultural relationships as discussed below.

Positive narratives and the COVID-19 impact

Bottom-up cultural relations initiatives

There are different approaches to international cultural relations including bottom-up ones that have been playing a significant role in maintaining a cross-national dialogue and promoting national interests, albeit from non-state actors.

During COVID-19, numerous noteworthy bottom-up approaches have been witnessed. While being connected to their devices and disconnected from their ordinary lives, global digital users have joined efforts to lift spirits and show solidarity with their neighbors, friends, communities, compatriots, and beyond. Nationalist messages have circulated across social media and were picked up by traditional media to virtually support communities and continue building cultural bridges and relationships within and across countries. For instance, when the pandemic was first declared, and some countries started imposing confinement or lockdowns, uplifting and solidarity videos were shared by people across countries. This included videos of citizens in Italy singing the national anthem and others from several countries where individuals in windows and doorways were applauding healthcare workers for their efforts. Arab countries also had similar social movements. In Qatar, for instance, members of the Qatar Philharmonic Orchestra played from their balconies to spread hope and lift people’s spirits (The Peninsula 2020).

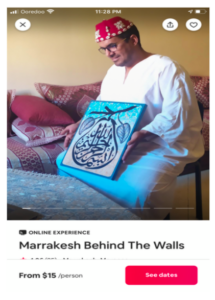

Other bottom-up approaches have emerged from citizens keen on maintaining their global connections for diverse reasons. In the picture below (Fig. 4. Experience Marrakesh on Airbnb), Airbnb host and tour-guide Hicham presents a 60-minute session on Zoom about Marrakech, its history, culture, and inhabitants. The popular walking tours he would have hosted in person if tourism was available during the coronavirus were offered as an online Airbnb experience. Despite the pandemic, it is individuals that have continued to take initiative and act as agents for the economic and cultural connections in countries where institutional systems are dysfunctional.

Fig. 4. Experience Marrakesh on Airbnb

Other grounded, bottom-up cultural initiatives in the region have taken place on the trendy platform TikTok. Conversations on TikTok in MENA increased 148 percent between March 15 and April 15, 2020, and have revolved around family values, traditions, and stereotypes associated with their cultures (Talkwalker 2020). Youth engaged in exchanges about their habits and the mindsets of their families, but also simply about common mores. Parodies, pranks, dances and activism all appeared on TikTok—despite some governments’ repressive practices. For example, some Egyptian teenagers were accused of violating public morals and jailed because they danced on TikTok wearing heavy makeup and were charged with “being provocative” by Egyptian prosecutors (DW 2020).

TikTok's popularity among the youth has driven health organizations and NGOs to spread their coronavirus-related messages through TikTok and its influencers. For example, during the outbreak of COVID-19, a hashtag #MaskUp campaign launched by UNICEF MENA in April 2020 received more than 136 000 mentions by May 2021 (Unicef 2021). Other popular bottom-up initiatives include TikTok video campaigns that address and fight against misinformation and disinformation about the coronavirus.

On the cultural organizational level, in several countries, museums and libraries opened their databases, archives, and exhibitions. They made these resources accessible for free for users worldwide to consult and enjoy at home. The Doha Film Institute, for example, organized talks and conversations around award-winning films and documentaries. Locally-based international organizations, such as the British Council, also launched initiatives to enhance cultural relations in the countries in which they are based. In Tunisia, the British Council launched a remote program for kids and made its library accessible for free. Such initiatives blend with the UNESCO declaration of principles of international cultural cooperation and consolidate the cultural opportunities and benefits for those involved and those who participate. Once again, all these initiatives are offered remotely, through websites—and most often—through social media. It is fair to say that social media use has proved to be the symbolic resistance to the coronavirus, especially for the highly-connected Generation Z. Whether it is on television or streamed online, media content remains an essential vehicle for cultural diversity and international cultural relations.

Media content as a proxy for international cultural relations

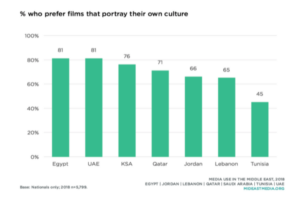

Media content promotes social and cultural meaning. The cultural industries, in general, have long been used as soft power tools in cultural diplomacy when a country has needed to disseminate a certain message or image abroad. Exchange of cultural content through movies, books, series, and music promotes diversity and openness to learn about others’ cultures. At the same time, consuming cultural products from one’s own country enhances one’s culture and social heritage. Recent data shows that MENA audiences have mixed feelings about watching foreign content vs. local content (Dennis et al. 2018). The Media Use in the Middle East survey asked Arab users how much and in what way do they appreciate their cultural experiences through the media (Dennis et al. 2018). The majority of respondents in MENA agreed that they benefit from watching international content. But also, most of the respondents from the seven countries surveyed said that they prefer watching films about their own culture (Fig. 5 Arab respondents who prefer content that portrays their culture).

Fig 5. Arab respondents who prefer content that portrays their culture (Dennis et al. 2018)

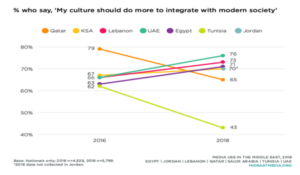

At the same time, however, many respondents thought that their culture did not do much to integrate modernity. In fact, except for Qatar and Tunisia, more than 7 out of 10 respondents said that their cultures should do more to integrate with modern society.

Fig 6. Arab respondents vis à vis modernity (Dennis et al. 2018)

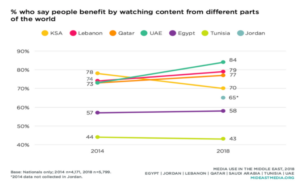

Compared to a 2016 survey, in 2018, more Arabs found that films and Western TV programs have been ‘good’ for morality. However, there is no consensus about whether people benefit from watching content from different parts of the world. In Tunisia and Egypt between 2014 and 2018, about 4 and 5 out of 10 people, respectively, see some benefit in watching content from different parts of the world. The number of Saudis who said they see some benefits dropped slightly to about seven out of 10. About eight out of 10 in the UAE, Qatar, and Lebanon agreed to finding a benefit in watching content from different parts of the world.

Fig 7. Benefit by watching content from other countries (Dennis et al., 2018)

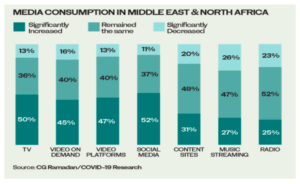

During COVID-19, both TV consumption and usage of streaming services have increased. Global and regional streaming services, like Netflix and Shahid, have reported growth. Shahid, owned by the MBC group, reported a ten-fold audience growth since the beginning of the pandemic (Khamis 2020). The CEO of the streaming service StarzPlay Arabia, Maaz Sheikh, noted that in the Saudi market, it took the company two years to reach two million minutes per day, while it took six weeks only to move from 2 to 6.5 million minutes per day by mid-April 2020 when confinement was imposed on people (APOS 11th summit Sept. 2020). Thus, there is a significant organic demand for content, as displayed in the following chart, and people are willing to pay a premium to access international content.

Fig 8. Variation of content consumption under the COVID-19 pandemic (Choueiri Group Ramadan/COVID-19 Research; Communicate 2020)

Similarly, after the coronavirus outbreak, podcasting soared, presenting even more opportunities for exchange and dialogue. Some podcasts saw a doubling of their audiences; others acquired extended broadcast time and broader reach. Between January and June 2020, Podeo, a Beirut-based, MENA-wide podcast platform and podcast production house, grew 450%, and it is estimated that about 1000 podcasts are currently operating across the region (Nabbout 2020). Research carried out during the COVID-19 outbreak shows that more women in MENA listen to podcasts than men (Campaignme 2020). The level of trust accorded to podcasting is higher than in any other medium, with at least nine out of 10 respondents saying they trust podcasting (Campaignme 2020). This is in striking contrast with users in the US and UK, who have the least trust in podcasting (GlobalWeb Index, Coronavirus Research Report 2020). The high trust level in podcasting can be explained by the little trust Arab audiences have in their mainstream media in general. The Media Use in the Middle East survey notes a decline in trust in the five countries studied over 2015-2019 (Dennis et al. 2019). New media platforms could be welcomed by audiences when they represent a breakthrough from less trusted media sources.

While it is a tough time for culture and cultural initiatives in countries where there is little support for cultural institutions, regional and international solidarity from and among non-governmental organizations is another symbol of resilience in the face of COVID-19. The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) ensured free viewing online (March-May 2020) through its Screens-and-Streams program. The International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) facilitated the free screening of documentaries for a limited time. The Artist Support Grant, Ford Foundation, Open Society Foundations, and Spotify pledged support for artists across MENA. AFAC and Netflix also announced an emergency relief fund to support film and community TV in Lebanon and other organizations like the Culture Funding Watch or the Anna Lindh Foundation. These are initiatives funded and organized by the private sector and independent philanthropists that have been the most active in funding and promoting cultural creativity before and after the pandemic.

Initiatives and opportunities for the educational sector

While it is true that measures and initiatives issued at the institutional level throughout MENA have been insignificant and have had little impact, COVID-19 has provided ample opportunities for regional institutions to work together and build better educational and cultural infrastructures across the region.

The Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization (ALECSO), an institution of the League of Arab States that aims to coordinate cultural and educational activities among Arab countries, called for an extraordinary meeting with the Ministers of Culture from all Arab states and another meeting with festivals’ directors. The meetings discussed experiences and individual responses to the crisis. However, no statement on common policies or agreements was issued. One must note that ALESCO’s weak position in issuing any abiding statements or treaties lies with its mother organization, the League of the Arab States, which has been dysfunctional for years and ineffective in mediating between states or producing binding statements on any kind of issues. Yet, ALECSO has produced some noteworthy educational initiatives, including its Arabic Open Educational Resources hub with platforms that provide free access to educational material and resources (under the creative commons license).

Member countries have launched individual initiatives, some of which are accessible across the region. For instance, in the UAE, Dubai has offered worldwide access to Madrasa [“School”], an eLearning platform for students of all ages that includes curricula in languages and sciences. In Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Lebanon, online learning systems have been introduced and used to continue remote education. New learning platforms have been launched in Jordan and Lebanon, while in other countries—Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon, Egypt, Oman, and Qatar—TV-based learning has been a more common alternative (UNESCO 2020). These have been ad-hoc solutions but could serve as foundations for the individual states to build long-term infrastructure to embrace online education and ensure more equality between private and public schools. They could also serve as a foundation for regional and inter-country conversations to build synergies and exchange programs that can encourage travel across the region and bring value to students in both urban and rural areas.

Another tripartite statement dealing with recommended initiatives to address the impact of COVID-19 was issued jointly by ALECSO, the Arab Bureau of Education for the Gulf States (ABEGS), and the Islamic World Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (ICESCO). The statement (ALECSO 2020) includes a list of new initiatives such as the launch of a distant-education website, preparation of an information booklet to prepare parents and educators for digital education, and the organization of distant-training workshops. Additionally, the ALECSO will call for donors and partners to sustain and improve the distance-education infrastructure.

It appears that no policies have been issued by any Arab states coalitions, although some conversations relating to education were initiated and some recommendations were made. Arab states have addressed their recovery or support programs independently: Tunisia planned and announced its government-issued relaunch program, le Fonds Relance Culture; Algeria’s National Copyright and Related Rights Office issued an exceptional grant for artists to support them through COVID-19; Saudi Arabia launched a support fund for filmmakers; the UAE created a national creative relief fund program for citizens and non-citizen creatives, which will underpin all local programs.

The post-COVID-19 era will be critical for governments, policymakers, civil societies, and individuals. It is an opportunity for these agents to reevaluate their priorities and revise their support for cultural relations. One way to support cultural relations is by promoting and funding research pertaining to cultural relations, including opportunities for building cooperation through cultural relations programs, especially during crises. In doing so, MENA stakeholders will be able to develop partnerships and allow academics and civil society to broaden the conversation and engage in efficient programs.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub