Issue 23, winter/spring 2017

https://doi.org/10.70090/CG17TIPD

Abstract

The article deciphers the symbolic deconstruction of the Israeli Indignant Protest (2011–2012) on behalf of the local cultural simulacrum—based on Zionist narratives of Judaism. It presents, through the subjective eye of a participant observer, the symbolic paradigm by which the protest opened its way through street poetry’s contemporary representation, including in this concept poetry, prose, songs, pictures, memes, graffiti, and other social media and street phenomena.

When on July 14, 2011, the young Israeli woman Daphni Leef pitched a tent on Tel Aviv’s Rothschild Boulevard—the center of Israel’s bourgeoisie—and protested against the high cost of rent, the Arab as well as the Western geographies were already being altered by what became roughly known as the Arab Spring (2010–2013) and the Indignant Protests (2011–2014) (Castells 2012; Schiffrin and Kircher-Allen 2012; Flesher Fominaya 2014). Following Daphni Leef, thousands of middle-class urban young Israelis, as well as participants of the lower classes from all over the country, followed her example. In the Palestinian cities, under the influence of the Tunisian and the Egyptian Revolutions and of the Israeli “J14,” the agitation was quelled by the government of Mahmoud Abbas.

The Israeli “indignant”—as they were soon recognized—sought to rebel against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s neo-liberal policy. The accusing finger was particularly directed toward the capitalist policy favoring national security over education and social welfare and benefiting Israeli and international tycoons. In fact, the Indignant, inspired by the French Stéphane Hessel's manifesto Indignez-vous,[1] demanded that the neoliberal system, that totally subjects the state to the economy controlled by tycoons, and is usually based on military interests and the enslavement of Third and Fourth World resources, be abandoned. Furthermore, the J14 movement faced a more defiantly complex reality where, traditionally, the concept of “political” was reserved strictly for the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, which is, among other things, a clash between a system of oppression and over-expression and the desire for freedom, as well as between a post-traumatic ethos and an anti-colonialist struggle.

The following year, the political dimension of the social protest was being denied by the protest’s speakers. But, its second year highlighted the impossibility of avoiding designating the protest as political and raising this question for debate. In fact, every action has political significance when: (1) it makes reference to relations between different groups, or (2) between the collective and the state, and (3) when it occupies public space and modifies its significations. From another point of view, negating the ascription of a defined political identity (left versus right) served to authenticate the appearance of heterogeneity of the movement: the mainstream of the protest rejected any identification with absolute leaders. Paradoxically—or not—the J14 movement saw in every activist a leader, a maker, a clue toward change. This is to say that it was perceived by its members as a broad collective, composed of many different voices. More than once, however, this dynamic collective subject also reflected behavioral forms borrowed from Israeli hegemony through practices of silencing and discrimination, in service of the national simulacrum; these practices threatened the protest’s expressions several times and it was argued that its revolutionary characteristics were just expression of a “situational radicalism” (Monterescu and Shaindlinger 2013) or a temporary “mo(ve)ment of resistance” (Grinberg 2013).[2] Finally, the social movement did not get to say in a clear and definite voice that social justice would not be possible as long as all citizens throughout the “Canaanite” territory do not receive plentiful and equal civil rights.

Furthermore, the objection to using the word “political” and on taking a clear political stand also highlights the omission of the word “social” in the political narratives of all Israeli governments until today, which have subordinated the importance of the social to the state’s interests, which are almost exclusively focused on the various alternating geopolitical conflicts (with Palestine, Lebanon, Turkey, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and even Egypt). In fact, the Israeli protest brought out the inherent conflict between domestic and external political concepts, as well as between “content” and “form.” It is difficult to assert that its participants understood that a significant change in the content of Israel’s social strata would eventually lead to a change in the form or mode of the state, basically regarding its frontiers and its political organization. It would also mean, of course, the end of occupation.

On Methodology

This essay was written in parallel with the days of the Israeli Indignant protest, also called locally, based on a word play of the protest signs "ב' זה אוהל": “H [for home] is a Tent.” It was tackled as the travelogue of a journey to the semiotics of the protest (2011–2012). It aims to expose and understand the influence of the phenomenon on the progressive deconstruction of the hegemonic Israeli narrative ethos.

The first question that arose facing the blank notebook was how to describe an unfinished phenomenon, one still in formation, while the very act of writing meant feeding and materializing the same phenomenon. This question could be asked in the context of all theoretical studies conducted on a phenomenological basis; still, research that seeks to address a contemporary case in present time must simultaneously display its meta-poetic claim, not just in order to provide context for the work, but also as part of the methodological question itself: What grammar is the narrator to choose when she is an engaged participant observer? This issue is particularly pressing when the question has to do with the semiotics of the construction of a protest movement, which is as verbal, as visual, and as dynamic as was the Israeli protest. I chose to bring the narration of this travelogue as I wrote it down during those days: in a present time that I traversed to its last moment as an independent protester connected with at least two related social networks in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv (and a few connections with Haifa and Beer Sheba protests).

I propose this essay, then, as a journey through the protest space, whose nature is, to my understanding, linguistic and conceptual as much as material and demarcating a geographical territory (Marom 2013). This particular space was installed in the heart of the national culture, which I propose to understand here as a dramatic system of symbols (Geertz 1973) organized following a hierarchical hegemonic narrative; the space of the protest interacted with this semiotic system, but because of its spatial material nature, the actions it promoted overlapped the symbolic with the material and established a tense relationship disputing territoriality and power over the national cultural narratives. Although there is no intention to reach sharp conclusions over the possible significations of the semiotic net created by those symbols, I do mean to offer one possible analysis and, particularly, a working methodology on behalf of semiotics in the age of social-media culture.

Regarding interpretation, I acknowledge that having being part of the phenomenon, the hermeneutics I am able to propose are impregnated with my subjectivity. My main aim here will be, then, to open a dialogue with the cultural manifestations of the protest, which I propose to frame here as “street poetry.” With this concept, I make reference to poetic cultural products that exceed the traditional idea of “poem” and ascribe to the nature of “fiction” following the Aristotelian definition (Aristotle 1997) on aesthetic representation. When understanding fiction as promoting a parallel dimension to reality in such a way that it reflects its actions, feeds it and also modifies it, I highlight the important influence that those fictive elements exerted on the national cultural narrative. I also propose to understand “the street” in a broader perspective, where the urban space finds its continuity in social media or “media-space” (Marom 2012).

The semiotic dimension of the social protest in Israel was built by thousands of anonymous voices. Following the above-mentioned perspective, these are fictional voices—slogans, quotes and street art, photography (Rafaeli, Vilnai and Meroz 2011; Peled 2013), illustrations and Facebook statuses, protest songs and manifestos that elaborated the protest phenomenon both in newspapers and on blogs and that acted as “aesthetic activism” (Grossman 2011)[3] raising an “ethical call” (Kenaan 2013) addressed to passersby, readers, and media participants. I intend, therefore, to show how the semiotic dimension of the social protest established its bases in what seems to have been a first step before the “struggle” stage. Indeed, it is likely that the stage of semiotic change, which implies a deep and revolutionary change of mind among significant layers of Israeli society, is only a basic step toward what is to come. As with every process, the transition from the protest stage to that of struggle in the material dimension—if this separation can even be made—is slow, difficult, and progressive.[4]

Jean Baudrillard understood postmodern culture as a totalitarian symbolic construction covering the face of reality like a giant mask. He called this construction a “simulacrum” (Baudrillard 1981). The postmodern era—defined by Gianni Vattimo (1988) as a spatial location rather than as temporal—was understood by Baudrillard as producing a hyperreality disconnected from the object of its representation: reality; he also expressed the hope that the postmodern era would be susceptible to fragmentation—a postmodern statement itself—with the aid of guerrillas of symbols (1976). Despite its insufficiency for understanding the complex relation between reality and its postmodern representation as well as with the materiality of culture, I consider that the concept of simulacrum is highly suitable for understanding the semiotics of Israeli culture in the way they were highlighted by the protest. In fact, the Israeli culture was, since its foundation, quickly and overwhelmingly, produced as a mask that almost totally covers an extremely complex reality composed of historical elements that are reproduced through processes of desemantization and partial resemantization in order to fabricate a fitting relationship between the theological narratives regarding the land.[5] Furthermore, I perceive here the Israeli national culture with its semi-theocratic and nationalist ethos as, in some points, anachronistic in relation to postmodern Western realities—while Jean-François Lyotard (1999) in fact identified postmodernism as integrative to modernism; I propose to understand it as a culture where modern and postmodern modes coexist overlapped and produce an extremely particular spatial, historical, and cultural situation.

In this context, the Israeli protest ascribed to the postmodern vector “[waging] a war on totality” (id.: 82) first, being presented as non-political just as were the first Indignados in Spain and, second, relativizing their identification with a totalitarian ethos, but still emphasizing an ethical discourse. It should be highlighted that the individual cultural manifestations of the protest were, ideologically, one step ahead of the J14 movement and did not always represent the collective claim. Nevertheless, even when stimulating debate, they were rarely rejected.

The will to be seen as non-political can be explained in the local context where it is thought necessary to assert a clear difference between the popular sociopolitical movement and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, always understood in the country as a political dispute between right and left. This differentiation was apparently a means of including people from the entire political spectrum, but avoided clarifying the heart of Israeli neoliberal policy, which leans on an inherently militarist state, a state responsible for discrimination against large civilian populations, establishing immovable socioeconomic status, and perpetuating social disparities.

A Chronicle of the Protest

Everything began on July 14, 2011—hence the name 14J[6]—when Daphni Leef (Schechter 2012) announced to her friends she was no longer able to pay her rent and decided to put up a tent on Rothschild Boulevard, in Tel Aviv's cultural center. Many young people, some of them students, joined her that same evening. The next day, something unprecedented happened: hundreds of people brought tents and placed their furniture on the boulevard. The “tent protest” had begun, staying on the boulevard for two months—until the authorities forced evacuation—and spread throughout the country: during the following week, almost every city and village in Israel had a tent camp calling for “cheaper housing.” People in camps organized and soon declared their identification with their contemporaneous Spanish Indignados 15M, adopting their gestural language, used in general assemblies, along with their slogans and spirit of struggle. However, also the identification with the Arab Spring spirit of struggle was often put in evidence (Grinberg 2013).

During the summer of 2011, thousands of social relationships were created as well as a system for communicating between different assemblies. The discourse of “social justice” invaded social and cultural meetings and the mass media, especially focusing on issues of economics, education, and housing. Academics, journalists, and politicians approached the protesters and retrieved from them a demand in the form of an alternative economic plan: a (somewhat simulated) dialogue commenced between the protest movement and the government. By the end of the summer, the center of the protest (still excluding the periphery), with the assistance of expert academic economists, designed a utopian plan for a “well ordered society” (Yonah and Spivak 2012). In response, the government ordered that the camps be dismantled.

When the summer (July–September) of 2011 was over, the hegemonic voices of Israeli journalism declared that the Indignant protest had come to an end. But this was far from true. In September 2011, the tent protest in the central area of Israel was indeed dismantled, but this was not the case in the cities of the periphery and on the coast; in some cases, the tent protest survived the winter—in Sacher Park in Jerusalem, in Hatikva tent camp in Southern Tel Aviv, in the tent camps of Bat Yam and Kiryat Shmona, for example—and, in fact, these did not disappear during the whole subsequent year. In other cases, municipal authorities suppressed the protest, led by the homeless, finally ensuring their return to the cold streets.

Indeed, during fall and winter there was a strategic and sometimes successful attempt to silence the movement, but the spirit of protest did not go away, and on the contrary, media silence encouraged it to look for other modes of expression. One such mode was in the organization of social activists with the homeless, in a number of different groups, entailing a long and difficult struggle for public housing with the welfare authorities and the Amidar company, the latter responsible for the eviction of dozens of families every year. In Jerusalem, for example, the tent camp called “No Choice” (Ma’ahal Ein Breira), first formed during August 2011 in Independence Park (Gan Ha’atzmaut), became the organized struggle group “Hama’abara” (the transit camp),[7] composed of social activists, single mothers, and the homeless.[8] The Ma’abara began working to free abandoned buildings as a protest against the fact of hundreds of empty residences in Jerusalem while the homeless sleep in the streets.

The illusion that the housing protest was over shortly after it began was the consequence of intentional repression by the authorities, as well as of a sudden policy by journals, after the trade received threats from tycoons not to take advertising space if the protest against them was reported. The big publishing groups stopped reporting the struggle, and even began a campaign to delegitimize the young woman, Daphni Leef, the initiator and one of the heads of the protest. In consequence, the general public supporting the protest, but not involved directly in its activity that was organized through social networks, stopped receiving information on demonstrations and other initiatives, even while those were increasing and developing new different modes of action. This fact forced activists to focus on public relations and information-based field activities. One of the significant steps was the attempt by middle class young activists from Tel Aviv to reach the local struggles in the periphery. In what seemed to be at first an “educational” journey to the lower classes of the peripheries, the famous figures of Tel Aviv’s protest discovered hundreds of natural activists fighting for their own survival and learning to organize and shout out their silenced voices.

During the months of fall and winter 2011–2012, while the official media kept almost totally silent, social networks saw an unprecedented increase in debates on the struggle's issues as well as the creation of dozens of events, organizations, and groups. The social network meant the befriending of people across social status, as had happened inside the tent camps during the previous summer (Ram and Filc 2013). Facebook profiles, which earlier had been a tool of connection for relatives, friends, and workmates, became the host for reunions between comrades in the social struggle. Tel Aviv activists reached out to labor unions; other activists visited high schools and universities and tried to spread the language of the protest within the educational system. Seen as momentarily successful, the event of the protest was reported in schoolbooks the following year.[9] Other activists, like Idan Landau[10] and Barak Cohen,[11] among many others, successfully introduced concepts, perspectives, and op-eds to mainstream journals and various blogs, while others like the then student union head Itzik Shmuli—today a member of the Knesset—betrayed the protest and sat alongside the prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, who bears great responsibility for the neoliberal economy in Israel. Other activists engaged in a direct struggle with Tel Aviv municipality, while other middle class activists confronted winter in the poor quarters of the city, expressing solidarity with refugees by offering “Levinsky soup”—communal soup served as charity every Friday. On the labor union front, non-institutional unions expanded their activities and became more visible, especially Koach Laovdim (Workers’ power) and Ma’an—this latter, working mostly with Palestinian workers—even shaking the institutionally entrenched workers’ union Hahistadrut, which has traditionally strong political ties with the national government.

Mainstream media began reporting the protest again when the riot police arrived on Rothschild Boulevard in order to violently arrest Daphni Leef as she was trying to reinvigorate the tent protest during the summer of 2012. In view of the outbreak of police violence after her arrest, where other eighty-eight activists were brutally arrested, and the windows of a bank were smashed—apparently by agents provocateurs unrelated to the movement—Israeli journalism found it apposite to return the protest to the headlines. While reawakening to the protest, the media discovered new social and financial organizations such as: the cooperative supermarket “Beshutaf” in Jerusalem city center; the cooperative “Bar-Kayma” in southern Tel Aviv; a legal struggle for a new labor union of train workers disputing the Histadrut hegemony; the Ha’agala coop in Mitzpe Ramon; the Arab-Jewish association “Sindyanna of Galilee Fair Trade”—founded in 1996 and gaining visibility during the days of the protest; new communes; the “Beach Struggle” against coastal privatization; incorporation of Arab labor unions into the protest—as in the case of Ma’an; the struggle of school teachers against engagement of subcontracted employees by the Ministry of Education; running a non-institutional referendum as a form of direct democracy, offering an alternative to the 2013 state budget; debates over the protest in high school citizenship classes, and the attempt to include the orthodox population in the popular struggle as a response to the counter-protest of the “Freiers” (an Yiddish word for “suckers”), that aimed to place the blame for the socioeconomic crisis on orthodox communities.

The effect of summer 2012 was to reinforce the protest: firstly, by demonstrating by the arrest of dozens of activists on June 22th that the movement was indeed disturbing the status quo. Then came the first extreme act of despair on July 14, when the activist and homeless man Moshe Silman—perhaps following Mohamed Boazizi in Tunisia nineteen months before—after distributing photocopies telling the story of his confrontation with social security, in a huge demonstration exactly one year after the rise of the protest, set fire to himself, dying days later and hardening the hearts of his Indignant companions. Third was the intention of part of the movement to project the social struggle in the political arena[12] and knock on the doors of the Knesset, the Israeli parliament.[13] Indeed, if 2011 was a year of protest, 2012 revealed the progressive construction of social and economic alternatives.

While in the summer of 2011 many were afraid to highlight the imperative to include Israeli Palestinians in the Indignant movement, many other voices pointed out during the following summer that the struggle inevitably affects every single citizen of Israel, and also Palestine. The most radical voices of the protest were those who tried to found a new national party; their utopian manifesto contained their vision of a new state for all its citizens, a state without ethno-geopolitical borders:

Equality as a human value is at the root of our politics. That is to say, the political idea to be formulated devolves onto every human being living under the regime of the State of Israel. Whoever s/he is. To dispel any doubt, the political idea to be formed will affect Palestinians, Haredim, Mizrahim, Ethiopians, Russians, women, Bedouin, Druze, homosexuals, lesbians—in fact everyone living under the regime, even if not referred to in this short list. All this on the basis of equality.[14]

Internal conflicts of the protest

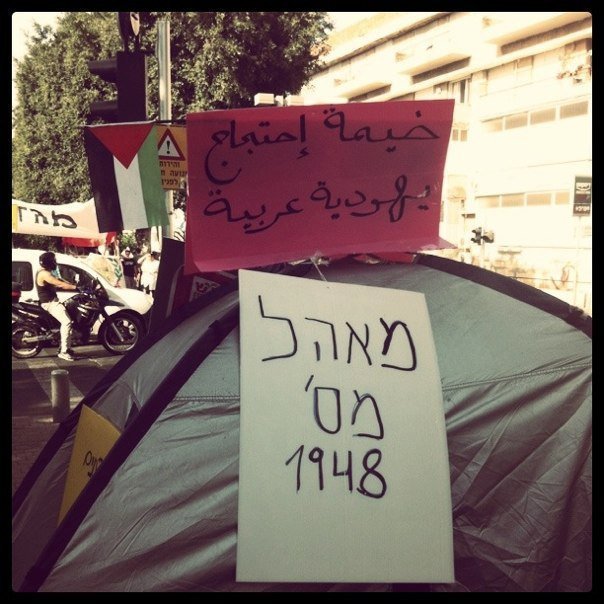

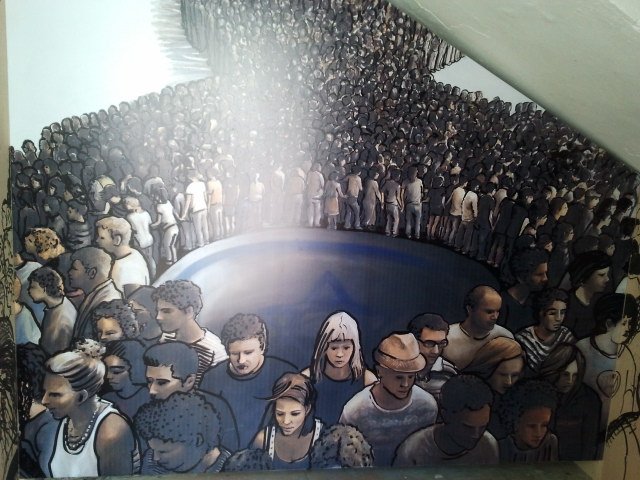

The inclusion of Arab labor unions was one of the protest’s most difficult internal conflicts. While the protest looked to represent “the people” from a broad perspective in terms of ethnic and social status, it stumbled over the most essential conflict of identity in Israeli society, in attempts to define who the Israeli people are. This amounted to a crisis of representation for the protest movement, since the inability of Israel society to define itself beyond hegemony and homogeneity disallowed the presentation of the struggle’s non-Jewish faces as representative. In one outstanding case, the Dror Group (youth related to Ha’avoda, the Labor Party) and activists from Hadash (the Communist Party) prevented the Arab representative of the labor union Ma’an, Wafa Tyarh, from making a speech—as was scheduled—during the June 2, 2012 demonstration. At this juncture, Ma’an-Da’am’s[15] head, Asma Aghbarieh, gave one of the most important spontaneous Indignant speeches of the protest,[16] from below the stage. She raged against the hegemonic tendency of the movement that appeared to be responsible for stopping the deconstruction of the traditional culture of social and ethnic stratification in Israel, disguised as it is in neo-liberal garb. There is no doubt that, at the end of the day, the conceptual Israeli-Palestinian conflict within the protest was the biggest obstacle[17] to a future development of the social struggle (Image 1).[18]

Deconstructing simulacrum through semiotics

Nevertheless, the protest carried out a de-automatization of the national political narratives, which possibly constitutes its most durable work. It is interesting to confront the response of the political system to the protest narratives, for it is around those conflictive edges where one can examine the protest’s potential to materialize changes. In fact, on those edges, the system’s response was definitively violent. After the summer of 2011, most municipalities composed new regulations making it strictly forbidden to erect tent camps within city limits.[19] Not all the camps were dismantled after summer 2011, however.

It seems that Daphni Leef’s tent, set up for the second time on June 22, 2012, was a symbolic threat to the nationalist roots sustaining the Israeli state’s simulacrum. That explains why the response to her new temporary settlement in the heart of Tel Aviv was violent arrest: ten anti-riot policemen against one citizen. In fact, Leef’s tent sitting in Tel Aviv’s mapped-out simulacrum introduced to the heart of the Zionist postmodern city an element of Jewish diaspora and Jewish nomadic behavior. Indeed, a tent, a hut, or another temporary dwelling symbolizes the Jewish past in the descent to Egypt, the time in the desert, the Babylonian exile, and the expulsion from Spain: an unfinished wandering far from Zion. As I read it, Leef’s tent symbolizes diaspora, which is “a historical model to replace national self-determination” (Boyarin and Boyarin 1993: 711), and this marks an opposition to the ideology on which the State of Israel was built. The Zionist ethos can almost be heard in the windy voice of the Judean Hills: the diaspora shall be reduced as much as possible and survive only in its function of serving the interests of the State of Israel; Jewish cultural life in the diaspora shall be minimized and all Jewish life taken under the wing of the Zionist regime. Israel will no longer allow temporary nomadic dwellings, and even the transit camps, the ma’abarot, which represented the base line for Israeli settlements, will be left in the past, as a heroic memory for the new nationalist Judaism. Nowadays, Israel conceives of itself as one of the most developed countries in the world. No option for new nomadic behaviors shall be allowed, there will be no more open spaces to explore, no movement towards new places outside the fabricated frontiers of the Land of Zion. In this sense, Zionism is “the subversion of Jewish culture and not its culmination” (id.: 712), it is even “its final betrayal” (id.: 717).

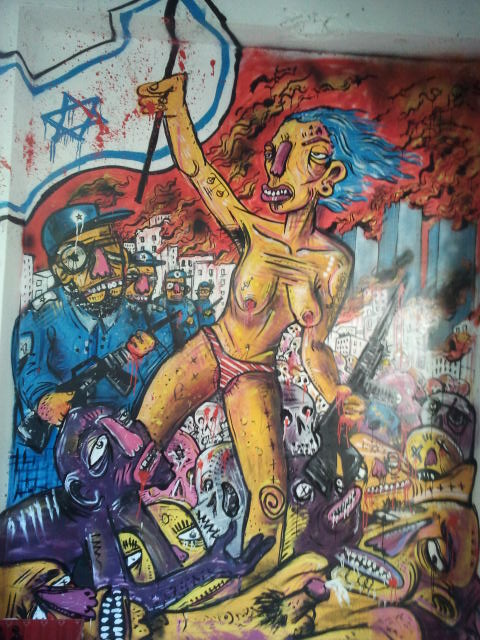

Consequently, Daphni Leef’s tent became a subversive symbol, an unbearable act menacing Zionist ideology, which uses all its strength and resources in order to forget or relativize a long history of worldwide coexistence—with its ups and downs—of which Jews were part before the Holocaust. A temporary dwelling menaces Israeli simulacrum. A tent may also be menacing to the ghettos Israel has revived, sometimes behind walls and fences, other times in its well-designed districts. If Jonathan Shapira’s graffiti on the wall of the Warsaw Ghetto in July 2010, “Free all ghettos” (Image 2),

was meant to highlight the urgency of overturning the walls between Jews and Palestinians,

Leef’s tent implies, too, a space for broaching questions and the possibility of self-critique, a revision of one’s own history, an almost nonexistent phenomenon in the construction of Israel national ethos. Perhaps it is, then, that the separation wall and the settlements not only lock up the Palestinians with no exit, but also banish Israel from the world, isolating it and eliminating the possibility of the rhizomatic dialogue that historically characterized Judaism and allowed for self-reflection and empowerment. Israeli policies toward otherness without a doubt harm the interactive and dialogical nature of Judaism. The harm includes: the invention of a completely new hierarchy—the Zionist Ministry of Religion—imposed also on rabbis in the diaspora; archaeological research mobilized around settlement interests; universities surviving on budgets paid for by Jews of the diaspora because the government invests citizens’ taxes on occupation and armament; or the state exploiting its citizens’ taxes even when that pushes entire populations into hunger and homelessness, denying access to vital education—these severely compromise modern Judaism. Israel has proven that Zionism and Judaism are very different things: the first, a colonialist practice; the second, an old culture in crisis. Daphni Leef, meanwhile, created a personal reflective space: a threat to the national simulacrum.

History registered the fact that more than half a million citizens followed Leef into the streets—seven percent of the entire population of Israel (eight million people), 10% following Grinberg (2013)—while the protest reached the whole of the Hebrew-speaking population through education and the mass media, producing a change in language by introducing into social discourse concepts such as protest, tycoon, struggle, labor union, social justice, equality, and social rights.

Once in the streets—the global space of popular empowerment (Monterescu and Shaindlinger 2013)—the protest made connections to other specific struggles for social and human rights, for example building solidarity with Sudanese refugees, the rights of whom, stipulated by UN regulations, Israel has failed to recognize, having instead later opened two detention centers (Saharonim and Holot) in order to discourage refugees to come. On May 24, 2012, when xenophobia took to the streets calling for a pogrom against Sudanese and Eritrean refugees in south Tel Aviv, protest activists responded to the horrible deja vu and stood by the refugees, going beyond their previous help in securing legal aid and providing soup once a week. The activists also blamed the government that had created a deprived ghetto and imposed a further burden on a weak population, composed mostly of people of North African Jewish origins, leaving them to house the refugees in an already poor zone. While shouting “Sudanese to Sudan,” the Israeli separationist discourse tried to hide behind another wall. The establishment, for a moment, breathed a sigh of relief.

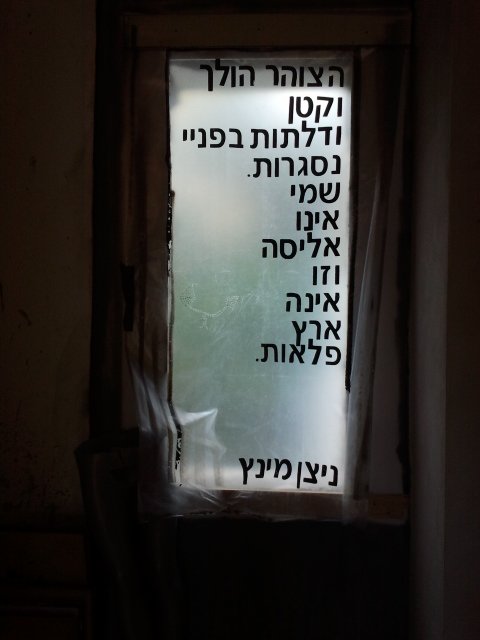

The accumulated fury is the consequence of a routine of injustice turned during this event on the weakest, who seem to threaten the only thing left: identity. Another cultural manifestation addressed this event showing a marginal character who sees himself in the mirror as if he was an actual victim of the Nazi regime, but in reality is himself becoming violent towards others (see image 3: “A problem with self-image”).[21]

The tattooed slogans on the body of the man with the “self-image problem,” the stereotypical Israeli xenophobe, say: “Death to Sudanese,” “Run over the orthodox,” “Let the IDF mow [expression for bombing Gaza],” “What aggression doesn’t achieve, violence does,” “Ethiopians to Ethiopia,” “A good Arab is a dead Arab.” The mirror displays not only the abyss between the real individual and the reflection of his unconscious, but also the antagonism between present and past. Both images are embedded in great violence, a demonstration that the Jewish tragedy did not end in Auschwitz, while its forms have changed. The caricature well illustrates that xenophobia is a reaction to consciousness of the Holocaust—as it was still bleeding, and in fact it is—an event that is manipulated by the Israeli simulacrum to justify violence, repression, occupation, and discrimination. The Holocaust appears here as a current state of mind. Furthermore, the mirroring image is not closed in itself because the picture plays a mirroring effect, an “ethical call” (op. cit.) addressing the real observer.

On July 14, 2012, Israeli Indignants marked their first anniversary, declaring that they had got stronger and their perceptions more accurate. The hungry and the desperate—those thousands affected by social security and in contact with welfare workers[22]—went out into the streets in order to shake up the system. The same day, Moshe Silman, a citizen of Haifa, active in the protest from its first day, distributed a letter among the demonstrators in Tel Aviv, recounting the maltreatment he had received, as a man with really nothing, at the hands of social security. He wrote: “The State of Israel stole from me and robbed me.”[23] He then set himself on fire. The fiery scene was a traumatic experience for the activists of the protest. It marked a point of no return: the protest became a struggle for life.[24] The conflagration of Moshe Silman produced a burst of questions and revealed the problematic welfare policy of the State of Israel, as well as the corruption and cynicism of the Amidar Company (responsible for public housing).

In fact, the man in flames wrenched another symbol away from the Israeli simulacrum. Fire that stands in Israeli national ceremonies for light, faith, and memory, became for the protest the flame of quest and inquiry. The Jewish mysticism of the Kabbalah interprets fire as transcendence and truth, in the scene when the biblical Moses—Moshe —discovered the voice of G-d in a bush on fire (Exodus 3: 1-22). The letters of the Torah are understood as inscriptions of black fire (Idel 2002). Moshe lighted a pyre in the hearth of despair and people gathered around it.

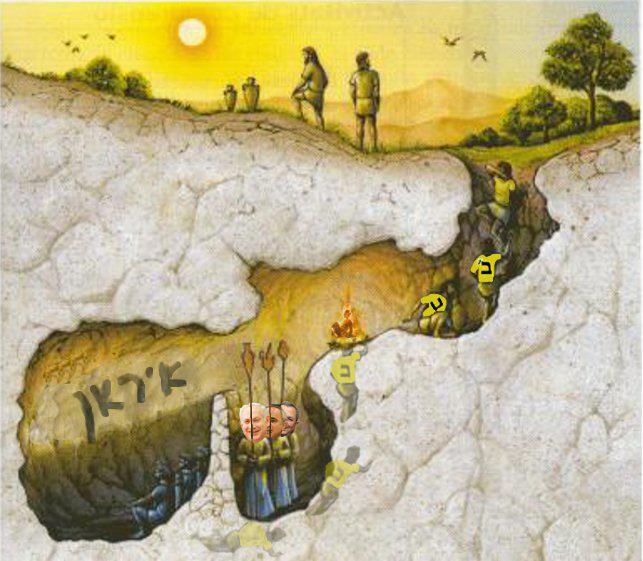

On July 22, 2012, the artist Amir Schiby posted on Facebook a Photoshop illustration titled “Platonic Digging” that transposes Plato’s myth of the cave (in Republic VII) to Israeli reality, where the perpetrators of shadows are the ministers of darkness—Benjamin Netanyahu, Yuval Steinitz, Ehud Barak—who try to establish the threat of death under the name of “Iran.” Meanwhile, the people of the protest—with the sign “bet,” ב, the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet, also meaning “home”—dig their way out of the cave (digging under the system) to the real source of light. Here, Moshe Silman appears as a double metaphor: he is the man sacrificed by the ministers of darkness to create a false light, but as the man of flames he also illuminates the path out of the cave. In fact, Moshe Silman appropriated fire—as Prometheus once did—and gave it to the daughters and sons of the revolution. Their eyes saw the inconceivable and their land was split. “The new Israelis”—as they were perceived by society in those days—now move through a narrow passage, with Moshe’s flame to guide them to an exit to a brighter place. For them, light is no longer a miracle, but consequence of a profound scream (Image 4).[25]

After Moshe Silman, other people set fire to themselves.[26] In Yehud, Akiva Mafai, a wheelchair bound IDF veteran, died by fire, and despairing others were only just prevented from torching themselves. But the mainstream media suppressed the information: items were even erased from electronic newspapers—censored indeed—and the government kept its silence, the phenomenon remaining unnamed, while Moshe Silman’s death was mentioned by the Prime Minister as merely a “personal case.”

After Silman’s immolation, new ways of acting were registered. Graffiti, alongside extinguished pyres, as signs of despair that also conveyed the menace of an imminent greater wave of indignation, appeared simultaneously on the facades of the National Social Security and Amidar Company buildings, saying “Price tag / Moshe Silman” "תג מחיר / משה סילמן" (image 5). The graffiti “Price tag/Moshe Silman” appeared in different versions including: “We are all Moshe Silman”; “Regards from Moshe Silman”; and “Moshe Silman is not alone,” in various cities such as Ramat Gan, Tel Aviv, Ramat Hasharon, Beersheva, and Jerusalem. The practice of “price tag” has its origin in settler attacks against Palestinian targets in occupied lands and against the police and army as a punitive reaction to the dismantlement of illegal settlements. “Price tag/Moshe Silman” is then a resemantization of this practice, that can be even read as a practice of poetic justice.

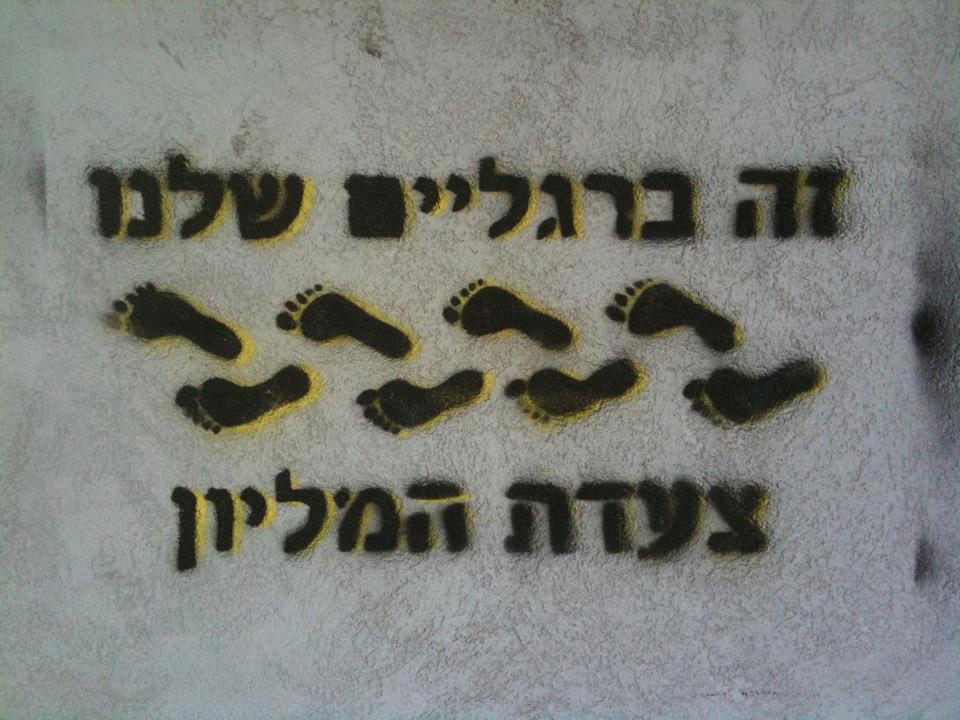

The cities witnessed other phenomenon of stencil and graffiti. The next image (6) is a stencil that appeared for the commemoration of the first anniversary of the protest towards July 14, 2012 and it inscribes: “We’re on our feet: march of the million.” Remembering the long path that still has to be walked, but the daughters and sons of the protest are on the move.

The scream, hence, will be projected as a long march. The epoch produced a feisty message written all over Jerusalem: “Keep walking little man” (Image 7: "המשך ללכת איש קטן").[29]

As the protest could be read here and there through the city, this repeated painting seemed to be saying the time has come to move on/again.

On June 29, 2012, a painting event was inaugurated on the walls of The House of the People, an empty three-flat building in Tel Aviv, a space opened during the protest. I will show several paintings that appeared during the “Painting the Protest” event in response to those trying to stamp out the new voice, the scream of the new generation (image 8).[30]

Just after Moshe Silman’s tragic death, terror gripped Israel again and Iran appeared in the TV channels as the unprecedented threat in the news. Two weeks earlier, the activist Gil Gultick, while travelling in Hong Kong, updated a personal tale on Facebook presenting the story of his encounter with an Iranian man, while a huge demonstration went on in the background:

Well if someone told me the following story I would not believe it: I am in Hong Kong on July 1, the day the island was returned to China after 90 odd years of British rule, so I go down to the port where there are awesome fireworks. On my way back to the city I hear the sound of a demonstration; well, I hold fast and then I realize that it is huge (the news said 400,000 people, sounds familiar doesn’t it? The police were talking about 63,000, somehow also familiar…) I take some photos and a Chinese guy comes up to me and gives me a five-minute’s lecture on what the rally is. I try to explain to him that I don't understand Chinese, but it doesn't really help and then another guy comes up (not Chinese) and asks me if I would like to know what the demonstration is about. I answer “of course” so he tells me there have been elections but they were fake—the Communist candidate won, raising much fear and concern in Hong Kong. I ask him from where are you from then he tells me I am from Tehran, Iran. We shake hands and I tell him I am from Israel, so after looking for nukes in each other’s pockets we just hugged. It turns out that he took part in demonstrations three years ago and spoke about it a bit. I told him a little about Israel and we were both satisfied with how the protests and demands for justice and liberty everywhere are. And that’s how I and the Iranian walk together, alongside many Chinese, through frightening/steaming [word unclear] Hong Kong.[31]

This testimony expresses how the establishment staged simulacrum is—at least momentarily—broken, even while it continues to chaperone people throughout their lives, offering itself as an integrative and built-in part of their consciousness. The teller experiences a surprising encounter producing a sort of revelation, capable of removing the cover of the national ideological fabrication. The revelation intensifies and even materializes with the realization that the other, the one supposed to be the enemy, him or herself also breaks the social conventions of his/her own nation and this creates a non-hostile and even empathic connection. In fact, a simple encounter appears capable of bringing the walls of dogma and the whole simulacrum rapidly crashing down.

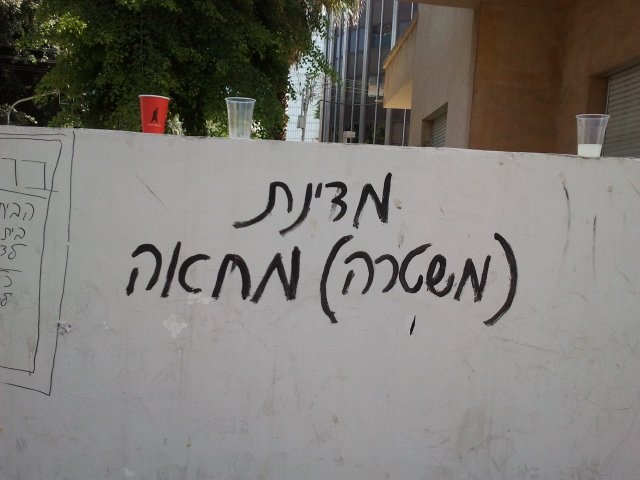

Indeed, one of the intentionalities of the protest was to substitute the regimented experience of the simulacrum with a dynamic Heraclitean experience embodying the wish to move in non-finite ways and exchanging the Israeli “Police State”—as chanted during demonstrations—for a Protest State (Image 9). This graffiti was painted at the entrance of The House of the People (Beit Ha'am) in Tel Aviv: “(Police) Protest State”).

Inside the House of the People, the protest exposed murals rejecting national symbols, turning away from the militarist, antisocial and anti-humanist era (Image 10) and

rejecting the state that has sold its body to militarized capitalism disguised under the flag of liberty (image 11). Here the State of Israel is materialized in the male chauvinist metaphor of the prostituted body of a woman, parodying the liberty of the French Revolution, painted by Delacroix.

The protest also confronted the semiotics of hope found in Israel’s national anthem “The Hope” (image 12).[32] This stenciled text was placed on a wall at The House of the People. It parodies and finally modifies the national anthem, with the promise of a new hope. The last line has been scratched out.

The English version of the anthem says: “As long as in the heart, within,/A Jewish soul still yearns,/And onward, towards the ends of the East,/An eye still looks toward Zion;/Our hope is not yet lost,/The hope of two thousand years,/To be a free nation in our land,/The land of Zion and Jerusalem.” My translation of the poem on the wall is: “As long as in the heart, within, /A soul still yearns/And onward to hell, forwards/ An eye looks toward the world/ Our hope still exists, /The hope is forever eternal/To be free in our land/… A new hope.”

In the reworked version, hope is expected to materialize through the collective social practice in the very present or the near future, and not through the voice of tradition, which focuses on the longing of diaspora for the Land of Zion. Hope also has been scratched out, intervened, the poem remains interrupted/with an open end.

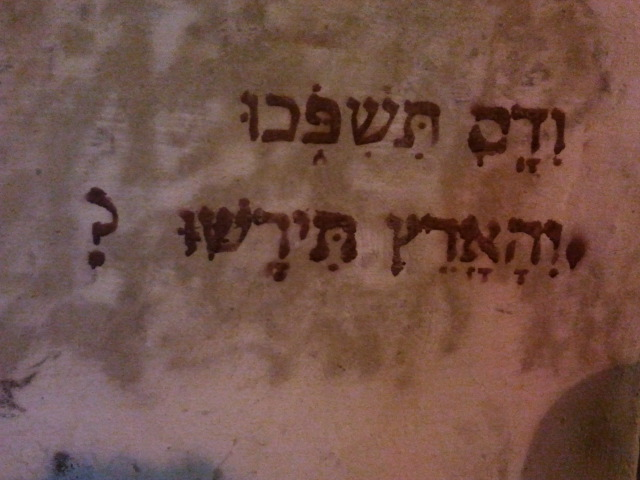

These manifestations wished to announce that the simulacrum shall fall to pieces in this very play of the semiotics of reality, and as a consequence of people filling the streets, and shouting their screams of despair (Image 13). A poem by Nitzan Mintz was painted on a window at the House of the People in Tel Aviv and said:[33] “The hatch is going / small / and doors in my face / close. / My name / is not / Alice/ neither is / this / Wonderland.”

The wonderful tale has therefore ended, the ancient hope lacks significance. Lastly, it should be asked where the people’s deep shout will lead (image 14).[34]

Will indeed the protest rise from its own ashes to kick against the simulacrum for another round? While the state becomes increasingly violent, will the protest find a voice, or will it let the blood flow as if this were the only way to inherit the right to walk on this land, to labor, and bring to it new life? The stencil found during the days of the 2012 protest in Jerusalem (Image 15) quoted the Biblical Book of Ezekiel 33 “You shed blood, should you then possess the land?.”[35]

Will the graffiti, the march and the songs be enough to restart democracy? Will the citizens of the modern Canaanite territory recover their rights over their own bodies: the right to live without being subordinated to the power of militarism and war, the right to move without borders, ghettos, check points, and fences? While the individual body becomes, in the social space, a bio-political reality (Foucault 1994, 1997), the protest appeared as an opportunity to question the state’s statement regarding bio-politics because the protest de-normalized the circulation of individuals in public space and what has long been normalized in the occupied territories subjected to Israeli thanato-politics (Agamben 1998) arose as molesting – from the Israeli status quo perspective—in the heart of a hierarchic society. Unfortunately, this mirroring relationship was never conducted by the masses of the protest.

The state has yet to respond to the interrogation: will you, Israeli state, become a constellation of sovereign human bodies or will you insist in the profile of a lump of meat serving quasi-cannibalistic causes? After the violent arrests of June 22, 2012, women protesters shouted “don’t touch my body” ("אל תיגע בגופי"), accusing the Yasam riot policemen arresting them of sexual harassment. The case brought the violent relationship of the oxymoronic forces of democracy with citizens into focus. The body is in fact a territory where freedom and violence can be measured. The violence exerted by the state against the protesters awakened the need to overcome the submission of bodies to the body of power, since every limitation on movement implies harassment, an impingement of individual liberty and dignity. The next stage of the civil struggle may be that of feminine strength breaking patriarchy apart, patriarchy on which the national simulacrum relies. In fact, a strong feminist awakening has occupied the social discourse after 2012 and feminist discourses intervened the protest arena in different marginal geographies (Misgav 2013; Fenster and Misgav 2015).

Four years after the Israeli Protest, and although it can seem that it has fallen apart, the social relations built during those days are alive. Hence, it cannot be understood just as a “mo(ve)ment of resistance” (op. cit.) neither as “situational radicalism” (op. cit.) but, I intuit, as a stage towards a bigger event or a deeper socio-political process, though I do agree to the characterization of the Protest as an event of “resistance” and to the need to relativize its radicalism since “the collective subject invoked throughout the protest was predicated on the exclusion of political alterities thus eventually undermining its own radical potential” (id., 230).

But, the fact is that the public discourse has slightly changed; the language of the sociopolitical order has been modified (Handel et al. 2012) and that cannot be undone: the simulacrum crumbles like the crying mask (image 16) of the modified Israeli flag, crying since July 2011, hanging from a building in front of the Habima Theater in Tel Aviv. Since the protest, the right-wing government has lost its integrity, and nowadays an internal chaos may further deconstruct the Israeli/Palestinian binational simulacrum.

Its melting makeup could reveal an unknown face.

This study has analyzed three symbols highlighted by the Israeli Protest—the tent, fire, and walking—and has presented the way aesthetic activism works in order to modify culture while dramatizing and re-signifying the symbolic web on which it leans. Symbolic modification of the national narratives of a culture is made possible during moments of political crisis, when language must reinvent reality to heal the wounds produced by injustice and collective suffering. These events also posed the present cultural questions on representation and showed the dialectics between postmodern cultural phenomena and the representation of modern objects it looks to elaborate. The symbolic modification, as presented, and the consequent weakening of biopower, is a silent process. But while the world goes on, everything begins and finishes with a sign.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub