“I heard em say the revolution won't be televised; Aljazeera proved em wrong, Twitter has him paralyzed.” So begins the hip-hop song that became an anthem of the Egyptian revolution, highlighting the key role Al Jazeera played in covering the uprising and the critical importance of Twitter to activists who helped organize the protest that led to the ouster of President Hosni Mubarak after 30 years in power. Egypt’s youth movements sparked the nationwide protest, inspiring people with Facebook pages, communicating via SMS and posting blogs with pictures and video of people in the streets for all the world to see. Mubarak tried shutting down Twitter and Facebook, but that only proved he was scared of the 4 million Egyptian on Facebook. His next move took the world by surprise.

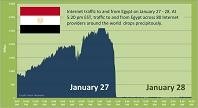

Shortly after midnight on Jan. 28 Mubarak took the radical step of shutting down the entire Internet and blocking mobile services. Weeks earlier Tunisia’s deposed president had blocked access to popular social media sites Twitter and YouTube, but nonetheless ended up fleeing to Saudi Arabia. With a population of about 80 million and a median age of 24, Egypt has nearly 4 million Facebook users, representing about 5 percent of the population. Facebook exploded in 2008 with the April 6 Youth protests and has doubled in the past year. Google, Facebook and YouTube are the three most visited sites in Egypt, and have been essential to digital activism in the region since Blogger became popular in 2005. In 2008 the April 6 strike page garnered 70,000 followers in about two weeks. In the first 24 hours the Khaled Said Facebook page had 56,000 followers. Twitter hashtags #jan25, #Egypt and #Mubarak were all worldwide trending topics for the first several days of the protests. And becoming a trending topic helps generate media attention, even as it helps organize information. The power of social media to help shape the international news agenda is one of the ways in which they subvert state authority and power.

Such a broad blackout in such an economically and politically powerful country is unprecedented, and raises significant concerns about the risk of doing business in countries where authoritarian rulers are deeply unpopular. Although Burma and Iran have attempted to do the same, Egypt’s successful blockage was a wake-up call to experts and officials who thought such a possibility was off the table.

Egypt has at least 200 ISPs according to official figures, but state-owned Egypt Telecom owns the country’s largest ISP, TE Data, which owned 70 percent of the country’s Internet capacity and had a 61 percent market share in 2010. On Jan. 27 it and the three other leading ISPs (Etisalat Misr, Link Egypt, Raya) were ordered to cut off access to the Internet and shortly after midnight they complied, casting Egypt into virtual darkness. The ISP Noor, which has a reported 8 percent market share, managed to stay online through Jan. 30 before caving. The speculation that this was because Noor serviced major international clients including Coca-Cola and ExxonMobil is well-founded. Since the government also owns the portals and pipelines that bring the Internet into Egypt and allow information to spread across the land, it was able to essentially block the Internet’s point of entry.

The government maintained the Internet blackout for five days, and the OECD estimated the cost at about $90 million, or $18 million a day, between 3 and 4 percent of the country's GDP for the period of the blackout.

Mobile phone operators were also targeted. Vodafone and France Télécom, a major shareholder in Mobinil, said the Egyptian government told them to shut off service. Their decision to comply generated enormous amounts of negative press around the world. Although they spoke out against the orders, they said they were hamstrung by national regulatory requirements. On Feb. 3 the companies were forced to send out pro-Mubarak SMS messages in a bold political commandeering of a private company that could inspire future interventions and represents a worrying intrusion into the freedom of companies to control their infrastructure, network and public perception. Vodafone also had to shut its call center in Egypt, hire 100 workers in New Zealand to handle the volume of calls, and fly 25 employees and their families out of Egypt.

The intrusion of the state into the communication networks of private, multinational corporations should raise a red flag for businesses in the rest of the region and beyond, wherever authoritarian governments and monarchies are having to contend with their own domestic uprisings.

And the full impact of the Egyptian state’s actions remain to be seen, though they have already been tremendous. Egypt’s economy came at a standstill after the outbreak of the protests, which drew millions into the streets across Egypt and kept the stock exchange, banks, schools and many businesses closed or understaffed for nearly three weeks. The Egyptian stock market plunged 10 percent in one day, the biggest ever one-day drop, and some ratings agencies downgraded Egypt. The uprising has also devastated the tourism sector, which accounts for about 12 percent of Egypt’s GDP. Although the full economic impact of the ongoing unrest in Egypt remains to be seen, some early figures are in. Analysts estimate that the economy has already lost about $3 billion due to the crisis. The long-term implication for the IT sector could be significant given Egypt’s efforts to become an IT outsourcing hub; last year the IT sector garnered $1 billion, though continued instability and a willingness to cut off the Internet – the umbilical chord of the contemporary financial system – raises questions about the viability of Egypt as an outsourcing hub.

Countries such as Egypt, Tunisia and the highly authoritarian but very wealthy Gulf states represent tantalizing markets, but the fact is that many multinational corporations have economies larger than those of many countries, and without access to their services and technology countries would be unable to compete in the globalized world. Companies such as Canadian-based Research in Motion, and Google, the US-based Internet search giant, should take a stand for the rights and values of the countries in which they started and grew. Without the benefits provided by the political and legal environments of Canada and the United States, these companies would never have been able to start up or grow into the innovative powerhouses they have become. There is a reason that few if any of the best 21st century technologies, or the most successful and innovative companies have emerged from authoritarian countries.

Yet, as the graph below shows, there is a growing market for Internet users and especially mobile phones in the Middle East countries currently being wracked by political protests. With the exception of Yemen, many of these countries are approaching near saturation of mobile markets. And their leaders realize the double-edged nature of these technologies, which are essential to conducting business but also useful for organizing protests. Last summer the UAE demanded access to Blackberry’s encrypted data streams following a protest against rising oil prices that was organized via Blackberry Messenger. Saudi Arabia, Egypt and other quickly follow suit.

Unlike RIM, which caved to demands by the UAE, Saudi Arabia and other digital dictators to grant access to encrypted and secure messages, US companies such as Google and Twitter have come out on the side of freedom by providing workarounds that enabled people in Egypt to use social media and evade censorship even when Internet and mobile services were cut. The workarounds included providing international landline numbers for Internet access, creating ‘speak2tweet’ that enabled Twitter posting via voicemail, and cloud servers. These solutions were publicized by people around the world through social media and experienced digital activists, like Manal and Alaa, who posted detailed instructions on their popular blog Manalaa.net on how to circumvent the near total blackout.

The digital blackout was, however, a powerful reminder of the power of older technologies, and innovative solutions emerged to merge the best of both. Landlines continued to be available, people in Egypt were encouraged to leave their wireless connections unlocked, and activists created wireless Internet relays to neighboring countries by stringing together access points.

The information economy of the 21st century depends on the free flow of information and integration into the world economy. But in authoritarian regimes the spread of information is an inherently subversive act. Twittering, Facebooking and blogging are all about spreading information and communication. And indeed the information revolution has helped bring about political revolutions in a region of the world considered ‘exceptional’ by so many in being inherently incompatible with democracy. The contours of the information society have made citizen journalism, social networking and other forms of digital activism one of the most potent and politically charged manifestations of power in societies where citizens lack access to the political arena and the media sphere is dominated by state interests. Throughout the Middle East, states control vast swaths of the media, usually including all terrestrial television stations, major newspapers and radio. And as Egypt’s audacious closure of the Internet and cooptation of mobile services shows, even those states with some level of privatization maintain an inordinate amount of control over the flow of information in their societies. Before the Internet enabled self-publishing and dissemination, there were really no mass media through which youth and minority groups could get their message out. But politically entrepreneurial uses of digital and social media by young Egyptians helped bring down a president who vowed not to give up and to die on Egyptian soil. Similar uprisings are underway in several other Middle Eastern countries, but it remains to be seen whether the governments will be willing to incur the economic costs of cracking down and how multinational companies will respond to the demands of citizens to be free.

Courtney C. Radsch is Freedom of Expression officer at Freedom House and an internationally published author and journalist with more than 10 years of experience in the U.S. and the Middle East. She is writing a book on cyberactivism in Egypt based on her doctoral dissertation and blogs about Arab media and politics at www.radsch.info.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub