“The power of American cinema is even greater than America’s military might. In the long run the presence of American cinema across the globe could create more problems than its military presence.” These provocative words are offered by the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami near the end of his documentary entitled 10 on Ten (2004). Ostensibly this is a documentary on the making of his film Ten, though it is also arguably Kiarostami’s masterclass on filmmaking in general. Like Ten, the documentary is divided into ten segments, each segment is introduced with a film editing leader number, thus making transparent that we are watching an edited film, or, put differently, a selected version of reality. In these selected versions we watch Kiarostami in the driver’s seat (presumably through a fixed camera on the passenger side); we hear Kiarostami in Farsi followed by an English voice-over. Kiarostami’s monologue, in effect, takes us behind the scenes of the art and craft of filmmaking.

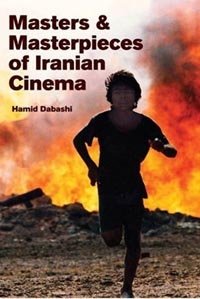

There is an uncanny resemblance between Kiarostami’s documentary and Hamid Dabashi’s dazzling new book, Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema. Dabashi’s book is a masterclass on Iranian cinema, guiding the reader on an equally labyrinthine journey which takes us behind the scenes of twelve films by Iranian directors.[1] Each chapter is focused on a single film, to which Dabashi brings a highly original and eclectic style of criticism, drawing on formal film analysis, scholarship on contemporary Iranian history, Persian poetry and prose, and autobiography.

Dabashi is a self-assured teacher and clearly impatient with the current state of film criticism on Iranian cinema, despite the fact that critics and international film festivals have been heaping generous praise on Iranian films over the past fifteen years. Dabashi’s critical project can be summarized in relation to the different audiences he is addressing. First, the entire book is written as a “Letter to a Young Filmmaker” who belongs to the generation born after the Iranian revolution in 1979. Dabashi self-consciously writes as a pre-revolutionary Iranian exile living in New York. From this self-location, Dabashi writes, on the one hand, in order to ensure that the next generation is able to fully appreciate the artistic and historically significant achievements of Iranian cinema; while, on the other, highlighting individual struggles endured by Iranian directors in creating their art – not only focusing on their personal existential challenges but, more importantly, their resistance to repressive political systems under the Shah and the current Islamic Republic. This is the dominant leitmotif shaping the structure and prose style of the book, which at once manages to skillfully celebrate Iranian cinema as both a unique inheritance and gift to the world while also underscoring the dangers of forgetting the yet unfinished struggles of Iranian artists against authoritarianism in Iran. For example, Dabashi asks the reader:

Have the horrors that Iranians as a nation experienced in the course of a monarchical dictatorship, a violent revolution, a devastating war, a brutal theocracy (and yet they have managed to hold their heads high, fight for their freedom from domestic and global tyranny, and still find time, energy and enthusiasm, care, love, intelligence, and humour to remind everyone of their collective humanity) resonated with some deep fear and offered it a soothing metaphor? Look at the lonely planet – every day and every night someone somewhere in the world is watching an Iranian film…Iranian cinema is the window of the world upon its own garden.” (359)

Western critics of Iranian cinema are the second audience Dabashi is addressing – the very same critics who have championed the universal humanism of Iranian films. Dabashi is unambiguous about his strong objections to aesthetic judgments framed solely in terms of humanism: “Iranian aesthetics are entirely purposeful and have emerged from the pain of the suffering we have as a people endured. Do not let a saccharine and generic “humanism” assimilate the specificity of your cinema – the blood and bone of its reality….”(22) Instead, Dabashi offers historically rooted readings, which illuminate the rich and intense conversations with Persian literature and contemporary Iranian history that are being staged, mediated and even invented through the films he has selected for analysis. He gives “blood and bone” to the lives, predicaments and themes explored by Iranian filmmakers, and in the process demonstrates how much is missed or glossed over when Western film critics read Iranian films simply through formal aesthetic categories associated with European humanism.

It is quite a revelation to learn of the extensive crisscrossings between contemporary Persian literature and Iranian cinema. This is particularly significant for understanding the pioneering films by the poet Forugh Farrokhzad and the short story writer Ebrahim Golestan; moreover Dabashi brings to light numerous film adaptations of novels and screenplays by novelists. Dabashi draws extensively on continental philosophy and literary theory, freely applying concepts from the writings of, for example, Adorno, Baudrillard, Derrida, Heidegger, Lacan and Levinas. Although many of these applications are critically stimulating, on the whole they become unnecessary and repetitious digressions from key arguments of this fine book. For example, Dabashi classifies the styles of Iranian film directors around an idiosyncratic theory of realism, as a way of distinguishing Iranian films from the aesthetic categories of Italian Neorealism, Soviet Social Realism, French New Wave, and German New Cinema. Yet after several close readings, I am still at a loss on how to understand the distinctions that Dabashi has in mind when referring to Kiarostami’s films as an expression of “actual realism” (283); Makhmalbaf’s as “virtual realism” (358); Ovanessian’s as “spatial realism” (138); Meshkini’s as “parabolic realism” (369); Panahi’s as “visual realism” (394) – or in his coining the generic term “Iranian pararealism.” (444) The cumulative effect of these multiple (and adjectival) uses of realism is to empty the concept of any meaningful content. At best, Dabashi is not really expounding a theory of realism in film, but simply using the concept of realism to support his aesthetic judgments, as in the following observations on Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf and Naderi:

Makhmalbaf’s cinema is scarred, just like his body and the soul of his nation. Makhmalbaf’s realism is virtual, because the full reality it wishes to convey and contest is too traumatic to bear. He has neither the panache nor the patience of Kiarostami to witness the actuality of reality (hidden under its overburdened symbolism), nor the steely eyes of Naderi to look reality straight in the eye without submitting it to any metaphysics. (358)

There is also a third, more general, audience that Dabashi is addressing, namely, a Western public whose understanding of Iran is shaped solely by media stereotypes of fanaticism, backwardness and a ‘clash of civilizations’ worldview. Dabashi’s autobiographical excursions plotted through the book offer unforgettable vignettes of his meetings with Iranian film directors, which give a concrete and all too human face to their aspirations and struggles. We read about Amir Naderi’s moving and hilarious journey by bus from Tehran to London in order to attend the premiere of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in May 1968 – a journey which inspires Naderi to become a filmmaker. (229-233) We are also offered a vivid description of Dabashi’s bus journey with the Makhmalbaf family from Cannes to the village of Yssingeaux, where a special screening of Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s film Gabbeh was organized in order to promote Iran as part of the 1998 World Cup festivities in France. (430-435)

Throughout the book Dabashi skillfully positions Iranian cinema in relation to issues and questions arising from the economic and political effects of globalization, thereby illustrating not only the interdependent bonds linking Iran with the West, but also the myopic fallacies associated with both political Islamist and neo-conservative constructions of the world today. As such, it is a welcome compliment to his latest book Islamic Liberation Theology: Resisting Empire, which perceptively deconstructs these fallacies. Dabashi is a deeply learned and astute thinker, whose varied intellectual gifts place him in a unique position to help us imagine alternative futures for the tragic conflicts facing Iran today, and to give voice, as in this book, to the creative artistic, and intellectual struggles inside Iran, of which the fruits of Iranian cinema are but one expression – albeit a phenomenon studded with ‘Masters and Masterpieces.’

Farouk Mitha is Academic Course Director for the Secondary Teacher Education Programme at the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London, England, and author of Al-Ghazali and the Ismailis: A Debate on Reason and Authority in Medieval Islam.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub