Issue 5, spring 2008

https://doi.org/10.70090/IW09CSRC

The once bustling Nasr City Fair Grounds now stand empty. The hundreds of participating publishers have packed up, the exhibition stands dismantled and the thousands of visitors, scholars, students and families gone home with their new books.

This year marked the 40th Cairo International Book Fair (CIBF), the oldest and largest in the Arab world. But how does this milestone reflect the state of Egypt’s book industry? Today the country’s around 300 private and public publishers continue to face hurdles of censorship and low readership. While some experts argue that a new breed of gritty social realist literature is finding popularity among a growing reading public, ambivalent public and government attitudes towards censorship mean that certain areas will remain out of bounds.

One of the optimists is economist and social critic Galal Amin, author of Whatever Happened to the Egyptians? that won him the CIBF prize for best book in social studies in 1998. He attributes some of the improvements in the country’s book industry to the wider distribution of books and the emergence of new, more user-friendly bookstores. “Buying a book here has now become altogether a more pleasant experience,” said Amin at a book launch, joking about how until recently browsers were discouraged from touching books in bookstores. Amin also believes that as a result of globalization, people around the world are more prone to buy Egyptian literature as a means to learn about the Arab world. But most importantly, he credits the changing tastes of a new generation of Egyptians who would rather read and write about the social ills and hardships of average people rather than the nation’s past political wounds.

One member of this new generation of writers is the 51-year-old Dr. Alaa Aswani. A dentist by day, his two bestsellers, The Yacoubian Building (2002) and Chicago (2007), have rapidly propelled him to international notoriety. Aswani has been using his pen to draw reality checks on daily life in Egypt. Homosexuality, sexual harassment, political corruption, religious extremism, prison torture and cultural biases are some of the uncomfortable truths he tackles in his fiction. Aswani sees linkages between Egypt’s social and political ills: “I love my country but the situation is not very positive; I think we do deserve democracy,” explained Aswani, who is a member of the opposition Kefaya movement, once led by imprisoned leader Ayman Nour. “Mubarak has been in power for 30 years and he has the intention of pushing his son next,” he added.

Aswani’s message has caught on among younger readers. “Aswani’s books let people know what is really happening in this country,” explained a Coptic student who preferred to remain anonymous, asserting that he identifies with the difficult social conditions depicted in The Yacoubian Building. “This book is more for Egyptians than for foreigners,” said the young man, who read the book both in Arabic and in French. “It is to let those Egyptians who think that everything is fine in this country know that things are really not that good.”

Aswani uses literature to tackle the unsaid. “Literature must examine what people don’t discuss,” he stated. One topic rarely spoken about publicly is sectarian violence in Egypt. “Copts and Muslims speak of their common life but never about their religion,” said journalist and chairman of Citizens for Development, Sameh Fawzy, before adding emphatically: “The Copt – Muslim relation is taboo – it’s a no-man’s land topic.”

But Aswani does dare to address the question of discrimination against Egypt's Christians, through the voice of his Coptic characters such as the handicapped servant in Yacoubian and the successful doctor who emigrated to Chicago.

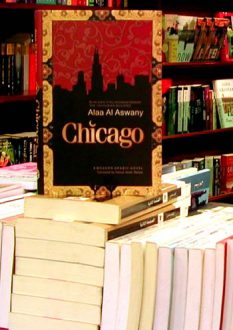

At the downtown Dar El Shorouk bookstore where Chicago adorns one of the main display shelves, Walid Abdel Fatah, head of the English section, expressed mixed feelings about the impact of shedding light on the taboos of Egypt’s society. “If we look at Islam, some topics from the book should have been banned,” he said, while leafing through the English hard cover edition. But after a moment of reflection, the young graduate of English literature added: “Talking about such things as homosexuality is good and bad at the same time because people don’t know that this exists in Egypt. Readers were shocked but at least now they know. That’s what literature should do, inform people and Aswani has a very good way of sending this message.”

Dar El Shorouk, established in 1942 and one of the 522 Egyptian publishers present at this year’s CIBF, is among the largest independent publishing houses in the country and most prominent in the Arab world. According to their senior editor, adding Chicago to their list of titles made perfectly good business sense. “We wanted to publish Aswani because he is the most successful Arab novelist in the region,” said Seif Salmawy. The Arabic edition has already sold well over 100,000 copies, where in Egypt a title is considered a bestseller if it sells 3000 copies over three years. Meanwhile, the French and English translations have sold 130,000 copies within the last year.

Chicago, like Aswani’s first novel, stirred up controversy for exposing Egypt's taboos - autocratic rule and political corruption, sexual misconduct and religious radicalism. Yet the book was not banned by the government. Nevertheless the writer, who also regularly bylines political articles, knows just where he stands. “The government does not like me very much,” noted Aswani. Yet in a recent column for the government-owned French-language Al Ahram Hebdo the prominent Egyptian editor-in-chief, writer and journalist Mohamed Salmawy lamented the declining status of Arab writers in their home countries. “Here in Egypt, the writer’s place has regressed enormously in the past decades,” said Salmawy, particularly condemning the way the media ostracize and attack writers.

Getting published was no small feat for Aswani who was turned down three times by government-owned publishers before signing with Merit Publishing House, an independent Egyptian publishing house that in 2006 received the Jeri Laber International Freedom to Publish Award for “demonstrat[ing] courage and fortitude in the face of political persecution and restrictions on freedom of expression.”

“Merit is an avant garde publisher,” said Aswani. “It already had problems with the government before publishing The Yacoubian Building,” he added. The book sold 260,000 copies in Arabic and has been translated into more than a dozen languages.

Looking back on his initial experiences with the local publishing industry, Aswani linked the difficulties for him and other new authors in getting published to Egypt’s political system. “… here in Egypt, we have many more troubles because the official system is not functioning. There is no democracy which makes things harder,” said the author.

Meanwhile the state’s General Egyptian Book Organization (GEBO), which organizes the CIBF, seems to be taking some steps to encourage new publications by posting step by step procedures in Arabic and in English on how to submit a manuscript and get it published by GEBO.

Like its writers, Egypt’s publishers are also confronted with setbacks ranging from high production costs, import and export regulations, to limited distribution, copyright and piracy, in addition to illiteracy and censorship.

According to a United Nations country assessment report, illiteracy in Egypt in 2005 touched about 30 percent of the adult population. "Today only three to five percent of the population reads books and these people are the decision makers," noted Dr. Hussein Amin, professor and chair of the Journalism and Mass Communications Department at the American University in Cairo. "And yet, the first verse of Surat Al-A'laq is Iqra bismi rabbikalla di khalaq (Proclaim! [or read] in the name of thy Lord who create --"). We should be a nation that reads, all of us read, "umht iqra' la taqra'…. The nation that should read, as stated in the Holy Qur'an, does not read,” he added.

Officially, state censorship does not exist in Egypt. Articles 47, 48, and 49 of the Egyptian Constitution ostensibly guarantee freedom of opinion, freedom of the press and freedom of expression in literature, art and culture. In practice, objectionable passages are often trimmed, or publications banned from import by government or religious bodies. During the CIBF in February, Farouk Hosni, Egypt’s Minister of Culture, reiterated the government’s official position of non-interference in artistic creativity but also stated that “Egypt is not Europe,” suggesting that its conservative religious customs make some limitations inevitable.

Questioning Islam, a sacrosanct taboo, can well attract the attention of Al Azhar University’s influential Islamic Research Council that has the authority to recommend to the government what books should be banned for the sake of preserving public order.

"There is greater freedom in the publishing industry now except if it offends Islam," said Amin. Government interference in opinions has let up in the past few years. "Censorship is now better than before," said Amin, noting that "if the work is of good quality," such as the novel Taxi (2007) by Khaled Al Khamissi, it has an even better chance of getting past the censors. "This is a Yacoubian society," noted Amin. "We need books like Yacoubian Building and if what we get is 90 percent of the books like it rather than getting nothing, it is better to have 90 percent," he added.

Chicago was printed in its entirety, without any cuts from the original manuscript. Although the government has “not recently” prevented Dar El Shorouk from publishing certain books, like most publishing houses, the management knows exactly where not to tread. “The red lines are clear: No pornography; no blasphemy; no state secrets [revealed] before 50 years,” explained Salmawy.

Keeping the red lines at bay and the censors out of his mind when he writes, Aswani adheres only to the whim of his pen and his characters. “I can’t write if I am afraid,” he said. “I am very loyal to my writing,” he added, “and I never know where my characters are going to take me.”

One of Aswani’s readers, the renowned Egyptian journalist and political writer, Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, phoned up the writer one day to express his appreciation but also to share some advice: “Never change any sentence if you are not convinced,” he told Aswani – something that he already seems to abide by.

Ingrid Wassmann is a freelance journalist living in Cairo. Prior to Egypt, she worked in the United Arab Emirates where she wrote for the Khaleej Times, Time Out Abu Dhabi, Emirates Woman, and Arabies Trends. Wassmann also worked for the French television channel Canal+ in Paris, and for the Italian daily newspaper Corriere della Sera in New York.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub