Issue 30, summer/fall 2020

https://doi.org/10.70090/AA203PEC

Abstract

The study investigates respondents’ perception of the negative effects of US drama binge-watching on their cultural values as compared with its perceived effects on the cultural values of others. The study helps in understanding the extent to which Arab residents in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) perceive media’s imperialist influence upon themselves as compared with others. It examines the perceptual and behavioral components of the third-person effect (TPE) in relation to binge-watching TV. Cultural background traits (individualism and collectivism) are studied as an intervening variable. The results showed that binge-watchers of US drama tend to perceive the potential negative influences of US drama to exist more for others than for themselves. The presence of individualist vs collectivist cultural tendency did not have a significant impact on the workings of TPE. The perceptual component of TPE was proved, while the behavioral component was not significant.

This research was funded by the Zayed University Office of Research 2019.

Introduction

As technology advances and media becomes more accessible, psychologists have inquired about the impact of media on human development and society, since the values and the everyday lives of its audience have been affected (Jacobs 2017, 1). Content originating in the US is well-recognized for having a powerful impact on the culture and values of people around the world. The attention on its impact is heightened when US media carry messages perceived to have negative effects on culture or society (Willnat et al. 2002). With the advent of new technologies—for example, online services like Netflix, which are popular among a large number of young people—limiting the negative impact of US and western influences is quite challenging.

The ability of digitalization to allow “interoperability” between television and other technologies gradually has led to a transformation of multiple aspects of television, including its technology, distribution, economics, associated media policy, and use (Mikos 2016, 154). The convergence between television and computers was a key outcome of interoperability (Lotzl 2009, 53). Rather than only being received using the conventional television set, television content can now be accessed from various platforms and technical devices (Mikos 2016, 155). As viewers began to use new technologies to watch TV content in different ways, they discovered that they had access to massive amounts of new content that they had never seen before (Colin 2015, 2). The result was a new era of TV watching behavior: binge-watching. Literature on binge-watching introduced many definitions. Walton-Pattison et al. (2016, 6) defined it as “viewing multiple episodes of the same television show in the same sitting.” Dickinson (2014, 9) specified the number of episodes a person watches within the day saying: “watching two to six episodes of the same show in one sitting or in 24 hours.” Warren (2016, 79) indicated that five episodes at a time would be a better cutoff point for examining how binge-watching affects viewers. Ahmed (2019) considered watching back to back episodes for 4 hours and more in one sitting as an indicator of binge-watching.

Binge-watching has been supported by a phenomenon known as media symbiosis, where people are using new media to watch traditional TV content more than ever before (Ahmed 2017, 205). The continuing evolution in new technology and internet services allows users greater control over the time and duration of their consumption of televised content. Considering these changes and their effects like binge-watching, it is important to explore how individuals view the impact of intensive watching of certain content, and how their perception of this differs from that of others. The findings of this study can help expand the existing TPE literature to the binge-watching context and provide theory-based suggestions on Arab cultural self-conceptualization.

In the Arab world, many media scholars, such as Al-Nemr (2010) and media professionals used to look at foreign (US and Western) media flows in the region as a real threat to their local culture and Arab identity. This study investigates how US drama binge-watchers in the UAE perceive its influence on themselves and other Arabs from various nationalities. Cultural self-construal (i.e., a person’s perception of their level of interdependence in terms of collectivism and individualism) is studied as a possible predictor of the relationship between binge TV watching and TPE. It also examines whether Davison’s (1983) third-person effect and cultural self-construal correlate with existing support for the censorship of US TV dramas in the UAE and the Arab world.

Recent TV-watching trends in the United Arab Emirates

Dennis et al. (2019) indicated that TV still holds its position both globally and regionally for long-form content with more substance, depth, and context. Users are consuming both longer and shorter types of content. They are drifting from the classic two-minute YouTube videos to the 23-minute episode on Netflix to binge-watching (i.e., watching entire series or seasons in one go), news GIFs, and 10-second clips on Snapchat.

Meanwhile, UAE Digital Media Statistics (2020) indicated that YouTube comes as the second most visited website by Emiratis after Google.com in terms of monthly traffic and minutes spent per visit. People in the Emirates prefer to stream content through the internet and the percentage of this streaming is becoming greater with each passing day. The report indicates that 64% of internet users stream TV content through the internet regularly. Dennis et al. (2018) reported that since 2016, the proportions of users watching content both online and on mobile phones have increased. Online viewing of TV shows increased most dramatically in the Arab Gulf countries in the past few years. It reached 56% in the UAE in 2018. Arabs under the age of 45 are two to three times more likely to watch TV programs in English than those 45 and older. The majority in the UAE say some of their favorite TV programs are not in Arabic.

UAE provides its people with various video streaming options. Some of the most popular on-demand streaming services in the UAE are OSN, Shahid, and ICFLIX. Netflix launched its services in the Emirates in 2016 and has become the go-to for viewers looking for the next show to binge-watch. The latest addition to streaming services in 2019 in the UAE is Apple TV+. Dennis et al. (2019, 37) stated that two-thirds of Emiratis report using a streaming service (like Shahid, Anghami, and Netflix, or others) in watching their preferred TV content. It was shown that Netflix is the most popular among Emiratis. In essence, Netflix proved to be among the most preferable platforms that Arab audiences use to reach global TV content, particularly US productions, which are said to affect their values and identity (Ahmed 2021).

Recent studies showed that drama is at the top of the list of preferred TV content that people tend to watch in the UAE. Dennis et al. (2018) reported that Arab women are more likely than men to list dramas as their genre of preference along with religious/spiritual programming, fashion content, and talent shows. Men, on the other hand, are more likely than women to prefer news, sports, and documentaries.

In her studies, Ahmed (2017, 2019) found that TV drama was rated highly in terms of most binge-watched content among Emiratis and UAE Arab residents. Indian, Turkish, Khaleej dramas, and US action, and European dramas were among the most frequently mentioned; while few respondents binge-watch Egyptian soap operas, football games, or non-Arab comedy shows.

In the seven-nation survey by Dennis et al. (2018), it was reported that in the UAE, drama comes on the top of the preferred TV content (51%) in 2018 compared to (37%) in 2016; that is followed by documentaries (43%) and (49%) respectively. There was a slight increase in preferring English language TV content over the Arabic ones in 2016-2018.

In 2019, the streaming service Netflix released ten fiction, non-fiction, and comedy shows that were the most watched in the UAE. Overall, the “Murder Mystery” movie was the most-watched title on the streaming platform that year, with “6 Underground” in second place, and “The Irishman” in third. All three are Netflix originals. The drama series, “The Witcher”, took the fourth spot. The top non-fiction favorites in the UAE in 2019 were “Tidying Up”, “Awake: The Million Dollar Game”, and the third was “My Next Guest.”

Dennis et al. (2018) concluded that education and cultural identity affect the language of TV content Emiratis prefer to watch. Nationals with a college degree are eight times more likely than the least educated nationals to watch TV in English. Also, nationals who self-identify as culturally progressive are more likely to watch TV in English than those who identify as culturally conservative.

Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

This study is based on a conjunction of three theoretical frameworks. The first is Davison’s (1983) third-person effect (TPE) hypothesis in which he proposes that people exposed to persuasive communication tend to perceive themselves to be less influenced by such forms of communication than others. The expectation is that others are more susceptible to such influence. The second is the literature on binge-watching TV (marathon TV watching), which was described as watching back-to-back episodes of the same TV content in one sitting (Wheeler 2015, 27). The third is the literature on media and cultural imperialism that discusses the impact on audiences’ values and culture from the consumption of foreign media, as well as literature related to the study of cultural self-construal (individualism vs. collectivism).

Third-person effect theory and binge-watching

Davison’s (1983) perceptual hypothesis states that people tend to believe they are less influenced, compared to others, by content perceived as negative and deleterious to one’s cultural values. This theory has been applied to a wide range of media content, such as pornography (Lo and Wei 2002), music clips (Ahmed 2006), advertisement (Henriksen and Flora 1999), political advertising (Cohen and Davis 1991), defamation (Cohen and Price 1988), and violence (Hoffner et al. 2001). Asian and European students who exposed themselves to US traditional media (newspapers, magazines, or TV) were more likely to believe that violent US media content affected others more than themselves (Wallnat et al. 2002, 186). The cognitive processes underlying TPE have generally been related to how and why social comparisons and contrasts are made. (Tsay-Vogel 2016, 1957) US drama, particularly examples that include violence, have been perceived as negative TV content that might affect its Arab audiences. (Al-Nemr 2010) This subject has attracted the attention of some scholars in Europe, Asia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singapore, among other countries. (Lee 1998; Hoffner et al. 2001; Willnat et al. 2002, 2007) Yet, this subject and related issues have been investigated primarily for traditional series or spontaneous TV watching, and not for binge-watching, nor were viewers from the UAE and the Middle East particularly examined.

This leads to the first research question:

RQ1: How do UAE respondents perceive the negative impact of US drama on self vs. others?

Most media programs, including TV dramas, are flowing mainly from the Global North and West to the East. As a sign of the emergence of new technologies that make US media products available to the audience all over the world 24/7 through internet live streaming and various websites such as Netflix, US drama was marked as a top favorite genre of televised content among various age groups in the Arab world (Ahmed 2017, 2019). Emiratis and UAE residents expressed that foreign, non-Arab TV soap operas were among their preferred types of televised content, which they increasingly binge-watched online (Ahmed 2017, 2019).

In terms of beliefs about positive or negative media influences, Lee (1998) found that few people in Hong Kong believed that foreign programs had negative effects on their values, behaviors, or ways of living. Instead, many of the respondents thought that foreign programs could increase their knowledge of foreign cultures and enrich their own culture. Attitudes about positive or negative influences have also differed cross-culturally with regards to whether such influence was experienced more strongly within or without the local culture or society. For example, Willnat et al. (2002, 188) found that European respondents tended to believe that US media negatively affected the cultural values of others more than their own, while this was not the case with Asian respondents. Lee and Tamborini (2005) found that students perceived the negative effect of internet pornography on others to be stronger than on themselves, which led them to support imposing censorship of such content.

While TPE has been widely supported in the context of social media (Tsay-Vogel 2016) and traditional media, including print, auditory, and visual media (Hoffner et al. 1997, 2001; Boynton and Wu 1999; Ahmed 2006), it is unclear whether TPE is still prevalent considering the new developments in TV watching behavior. Binge-watching has recently received attention from scholars because of the potential impact such constant consumption of TV content has on media habits, and people’s behaviors and beliefs. Binge TV-watching is defined as watching back-to-back episodes of TV content, enabling viewers to potentially consume full seasons in a matter of hours, and a full series in a matter of days. It combines two media outlets: traditional (TV content) and new media (online sites). Mikos (2016) considered binge-watching of television series as:

A cultural practice that viewers integrate into their everyday lives and adapt to their personal circumstances. The social conditions of their lives limit their consumption of series, like work, partners, and children demand a share of their time. (159)

Research on binge-watching has recently flourished, bringing in its wake some concerns about worrying consequences for the viewers' physical and mental health (Flayelle 2019, 26).

Based on the research on TPE and binge-watching, the first hypothesis is stated as follows:

H1: Binge-watchers of US TV dramas will perceive its negative impact as greater on others than it is on themselves.

Possible cognitive, affective, and behavioral effects of television violence may have stimulated more research than any topic in media studies. Controversy concerning television violence helps to reveal public beliefs about media effects. Although some people believe that television violence has a significant effect on other people’s behaviors and morals, others believe that they are unaffected (Salwen and Dupagne 2001, 211, 212). Therefore, the second research question was:

RQ2: How do respondents perceive the negative impact of violent US TV drama on self vs. others?

George Gerbner (1970) in his culture indicator analysis defined violent TV drama as the overt expression of physical force intended to hurt or kill. The cultivation theory by Gerbner (1970) investigated violent drama and its effects on the audience. Third-person effect theory examines the effects of a person’s perception of negative media content on self vs. others. The violent drama was one of the media content that is described as “negative”. In this context, Hoffner et al. (2001) examined the TPE in perceptions of the influence of television violence and found that the more people liked violent television, the less effect they saw on themselves relative to others on average around the world. Willnat et al. (2002) concluded that respondents in eight Asian and European countries perceived the effects of mediated US violence to be stronger on others than on themselves. Therefore, the second hypothesis stated:

H2: Binge-watchers of violent US TV drama will perceive its negative impact as greater on others than on themselves.

Davison (2003) discussed the relationship between third-person perception and censorship attitudes and highlighted that those who strongly supported censorship believed that the general public is adversely influenced by media messages, but did not admit to themselves that they were being affected by media messages. The third-person effect’s behavioral hypothesis predicts that people who are more likely to exhibit third-person perception are also more likely to support restrictions on media messages (Lee and Yang, 1996). This has been examined and supported by many researchers (Chia, Lu and McLeod, 2004; Hoffner et al., 1999; Salwen and Dupagne, 1999; Ahmed, 2006; McLeod et al., 1997). Willnat et al. (2007) found that Malaysian respondents were more likely to support censorship of US TV drama content because of its negative effect on Malaysian society. Therefore, the third research question formed as follows:

RQ3: To what extent do UAE respondents support censorship of US drama and violent drama?

Sun, Shen and Pan (2008) pointed out that:

Taking for granted a direct correspondence between the presumed exposure of others to a media message and its impact on them, individuals are more likely to partake in actions aimed at regulating the distribution and/or production of media messages under consideration. (260)

Willnat et al. (2002, 178) indicated that European policymakers have tried to restrict the amount of US television programming shown in Europe with the 1989 Television Without Frontiers directive, as per the Commission of the European Communities 1989. While the quota limiting US programming to 50 percent of European television was ignored by many EU members, countries such as France and Britain strongly supported limits on US media imports. This leads to the hypothesis below:

H3: Binge-watchers of US TV dramas in the UAE who perceive that US drama negatively affects others more than themselves are more likely to support imposing censorship.

- Cultural and media imperialism and TPE

Culture affects the way its members view themselves, their social environment, and their relationships with others (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Cultural imperialism theory suggests that media from one country will invade and colonize another, and the culture of the invading nation will seep into the receiving/victim nation. The victim nation is imagined to be culturally autonomous prior to the invasion, then under siege and culturally disenfranchised (Gray 2014, 984). Unlike the colonial enterprise, which was imposed in many instances by force of arms, cultural imperialism acts subtly until it gets to the critical stage of addiction (Akpabio and Mustapha-Lambe 2008, 261).

Cultural imperialism may be distinguished from physical colonization. Beyond the mere physical attacks associated with colonization, virtual colonization is a process that often outlives physical disengagement from the occupied territories. Victims may retain a “colonial mentality, a cognitive state where a victim is completely taken in by the propaganda of former colonial rulers, and this results in colonizers assuming a larger-than-life image in the minds of those so afflicted (Akpabio and Mustapha-Lambe 2008, 261). Noting how cultural imperialism presumes cultural malleability, Gray (2014) explains how receiving cultures experience trauma after the arrival of imperialists that changes the culture.

Communication imperialism, a form of cultural imperialism, suggests that Northern political and economic powers not only control the political and economic management of the world, but also have worldwide control over means of communication, and thus rule over communication flow (Sabir 2013, 284). Consequently, communication and media imperialism diminish cultural interaction, making it a one-sided process instead of a two-party exchange of cultures and values.

The closely related term “media imperialism” also implies a situation whereby the media system of a particular area of focus is subjected to the dictates of the media system of another area. The important issue here is the effect of media imperialism on culture (Omoera and Ibagere 2010, 5). Media imperialism emerged from the West, and it created an entirely new phenomenon; a media dominance that has controlled, managed, and changed the culture of developing countries around the world (Sabir 2013, 283).

Boyd-Barrett (1977) described several features of media imperialism: the shaping of the communication vehicle (communication technology); a set of individual arrangements for the continuation of media production, the body of values about ideal practice, and special media content. This study is concerned with the latter, that is, “special media content”. Omoera and Ibagere (2010) have argued that, in many countries compelled to view the world through the prism of Western values, ideas, and civilization, the influence of American media content only intensifies consumption values rather than production values (6). Consequently, this relegated the developing world as mere consumers of American media content.

The negative impact of US media on local cultures has been studied in various contexts, such as Nigeria (Omoera and Ibagere 2010), Malaysia (Willnat et al. 2007), and among Asian and European students (Willnat et al. 2002). Authors have discussed several reasons for the invasion of US media production in developing countries, along with ways to reduce their negative impact on local cultures and traditions. Willnat et al. (2007) proposed that culturally bound conceptualizations of self and others are likely to be good predictors of people’s perceptions of how self and others are influenced by specific media content.

Kim (1995) describes how individuals with independent cultural self-construal tend to see themselves as unique and value the ability to express themselves and act independently. On the other hand, individuals with an interdependent self-construal have the desire to be part of a social group and are less likely to behave in a way that disrupts the social order (Triandis 1989).

Gudykunst et al. (1996) point out that, while one culture can vary internally in terms of individualist or collectivist self-construal orientations, people in the US are more likely to perceive themselves as an individualist, while Middle Eastern people are more likely to perceive themselves as collectivist.

Willnat et al. (2007) concluded that the perceptions of US TV drama abroad (in Europe and Asia) are influenced by the respondents’ cultural values and, to a somewhat smaller degree, their exposure to US media. Lee and Tamborini (2005) found that students who perceived themselves as more collectivist (or interdependent) exhibited smaller third-person effects and were less likely to support internet pornography censorship. While Willnat et al. (2007, 16) found that respondents in Malaysia who exhibited interdependently (or collectivist) self-construal were less likely to exhibit the third-person effect and more likely to support censorship of US media .

Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

H4: Cultural background (individualism vs collectivism) of binge-watchers of US drama correlates to the perception of its negative effect on self vs. others.

- Control variables

Salwen and Dupagne (2001, 214) indicated that:

Biased optimism, one of the causes of TPE, which is tied to sociodemographic factors, such as age and education, may lead individuals to look at themselves and others in a self-serving manner as invulnerable to harmful media influences.

Hoffner et al. (1997) found that males exhibited a larger third-person gap (self vs. others) regarding mean-world perceptions, but females exhibited a larger gap regarding the acceptance of aggression and aggressive behavior. Perloff (1996) indicated that demographic variables, such as age and education, indirectly point to underlying conceptual factors that impact perceptions of media effects on others and self.

Boynton and Wu (1999) found that older respondents reported greater estimated effects of television violence on themselves than on younger viewers; additionally, females were more likely to perceive greater effects on others. Salwen and Dupagne (2001) tested the third-person effect concerning television violence to determine whether self-perceived knowledge is a stronger predictor of third-person perception than sociodemographic variables. They found that self-perceived knowledge was a stronger predictor of third-person perception than sociodemographic variables (demographics, ideology, and media use). Therefore, it was predicted that:

H5. Third-person effect differs among binge US TV drama watchers according to their age, gender, English language proficiency, and visit/s to the USA.

Methodology

- Data collection

The data were collected in July 2019 using an online survey disseminated to the Arab fans of US TV drama in the Emirates. The exponential non-discriminative snowball sampling technique was used to reach respondents who regularly watch US drama. First, the researcher identified the first ten people from her circle, who are known for being fans of watching US drama. They were five respondents from each gender from 8 different nationalities and three age groups. Then, they were contacted to fill the online questionnaire and each one of them was asked to share the link with another ten people from their circle. The chain continued until the sample reached the current size. All participants were informed about the aims of the study and asked to give their consent before starting the survey.

The criteria for participation, stated at the beginning of the questionnaire, were: being at least 18 years old and having watched US TV drama episodes regularly over the last six months. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed as respondents were not asked to reveal their identification. The questionnaire obtained approval from the Zayed University Office of Research in June 2019. It included 19 questions in Arabic, the mother tongue of the respondents. Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N: 257)

| Variable | % |

| Gender

Females Males |

72 28 |

| Age

· Less than 20 · 20 to less than25 · 25 to less than 30 · 30 and more · Missed |

25.7 36.6 21.4 14.0 2.3 |

| Nationalities

· Emirati · Egyptian · Palestinian · Jordanian · Syria · Sudan · Oman · Others |

48.6 5.4 8.9 10.9 9.3 3.5 2.3 11 |

| English language proficiency

· Fair · Good · Very Good · Excellent |

5.4 21.8 37.3 35 |

| Visiting the USA

· None · Once · Twice · Three times and more |

78.6 12.5 3.5 5.4 |

- Measurements

- Exposure to TV US drama

The questionnaire started with two questions designed to filter respondents to better reach the target category of US TV drama watchers. The first asked the respondent to identify the frequency of exposure to US Drama (Always, Sometimes, and Never), and the second asked about the type of US TV drama s/he tends to watch. Those who never watched US TV dramas were excluded and asked not to answer the rest of the questions.

- Binge-watching of US TV drama

This is the independent variable of the research. It was measured through three questions: first, the number of days per week in which the respondents are watching US TV drama. It ranged from one day a week to every day; second, how many hours a day the respondents watch US TV drama. It ranged from less than one hour to 6 hours or more per day; third, how many hours respondents watch American drama sequentially in a single session per day, whether on television or websites. The score ranged from 3-12, with a mean of 5.6 and a standard deviation of 2.16. Cronbach’s Alpha is .78.

- Third-person effect

I. TPE’s perceptual component

The respondents were asked four questions to measure the perceptual component of the third-person effect. They were asked how they perceive the influence of US TV drama and violent drama on their local cultural values and those of Arab youth (others). The answers ranged from “no effect at all” to “very negative,” “negative,” “positive,” or “very positive.”

II. TPE’s behavioral component

This was measured through two questions using a 5-point Likert scale. One asked about the respondent’s support of censorship of US TV drama in Arab countries to protect youth from the possible negative effects, and the second asked the same for the UAE. The answers ranged from: “strongly disagree” to ‘strongly agree.”

- The cultural background of the respondents: Individualism and collectivism

A 5-point Likert scale ranged from (5) strongly agree to (1) strongly disagree, and was adopted from Willnat et al. (2007) to measure the independence (individualism) and interdependence (collectivism) variables. 13 statements (listed in table 5) were used to measure independence or (individualism). The score ranged from 13-65. Respondents were divided into three groups high, middle and low individualism based on their score. Cronbach’s Alpha = .89.

As for the interdependence (collectivism), 13 statements (listed in table 5) were used to measure it. The total score ranged from 13-65, mean 50.5, and standard deviation 8.8. Cronbach’s Alpha = .89.

- Control variables

Demographic questions – age, gender (M, F), English language proficiency (excellent, very good, good, poor), and previous visit(s) to the USA (“1” Never to “4” three times or more) – were assessed to control for possible external influences on perceptions of US media effects.

- Statistical techniques

The data were analyzed using the SPSS.

The statistical tests used to examine the research hypotheses are reliability analysis, scale (alpha), means and standard deviations, Pearson Correlation Coefficient, T-Test, and paired sample T-test, and ANOVA.

Results

- Research questions

- Types of US drama the respondents tend to watch frequently

When respondents were asked about their most preferred US drama genre, 96.6% chose violence; which includes action, crime, and horror (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Respondents’ Preference of US Drama Types*

* Respondents can select more than one type

Comedy was the second (47.5%) preference, followed by romantic drama (19.5%).

- US drama binge-watchers perceive the negative impact of US drama as higher on others than on themselves

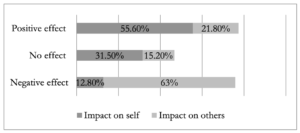

The respondents were asked about their perception of the negative impact of US drama on themselves and other Arabs.

Figure 2: Perception of the impact of US drama on self vs. others

The results in Figure 2 reveal that US drama binge-watchers tend to perceive the negative effect of US drama as higher on others, 63%, compared to themselves, 12.8%, while they perceive the positive impact as higher on themselves, 55.6%, compared to others 21.8%.

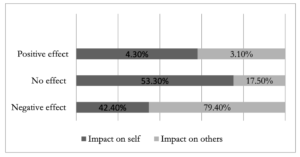

- US drama binge-watchers perceive the negative impact of violent US drama as higher on others than on themselves

When asked about their perception of the negative impact of US violent drama on themselves and others, US drama binge-watchers tend to perceive it as higher on others, 79.4%, compared to themselves, 42.4%, while they perceive the positive impact as higher on themselves, 53.3%, compared to others, 17.5% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Perception of the impact of US violent drama on self vs. others

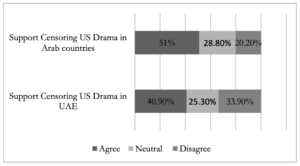

- US drama binge-watchers support censorship of US drama in Arab Countries

Respondents were asked about the degree to which they support censorship of US drama in the UAE and other Arab countries to prevent its negative impact on Arab youth. To make the comparison between the UAE and other Arab countries clearer, the frequency of Strongly Agree responses were combined with that of Agree, and the frequency of Strongly Disagree was combined with Disagree.

Figure 4: Agreement on censorship of US Drama

The results in Figure 4 explain that binge-watchers of US drama tend to agree on imposing censorship on US drama in Arab countries by 51% compared to 40.9% in the UAE, while 33.9% disagree that these shows should be censored in the UAE, as compared to 20% disagreeing on such censorship for Arab countries.

- Hypotheses testing

H1: Binge-watchers of US drama will perceive its negative impact as greater on others than on themselves.

Mean, standard deviation, and paired sample correlation were used to examine this hypothesis.

Table 2. Perception of US Drama’s negative impact on self vs. others

| Self | Others | Paired Samples Correlation | T | |

| Mean | 1.81 | 2.47

|

.474 |

-14.899

|

| Std. Deviation | .64 | .74 |

P< .000 df = 256

The results in Table 2 reveal that binge-watchers of US drama perceive its negative impact as higher on others (mean=2.47) than on themselves (mean=1.81). The difference between self and others is significant at (p<.00); therefore, the first hypothesis is accepted.

H2: Binge-watchers of US violent drama will perceive its negative impact as greater on others than on themselves.

Paired samples correlation was used to test the difference between the perception of the possible negative effect of binge-watching of US violent drama on self and others.

Table 3. Perception of US violent drama negative impact on self vs. others

| Self | Others | Paired Samples Correlation | T | |

| Mean | 2.38 | 2.76 | .393 | -10.389 |

| Std. Deviation | .57 | .49 |

P< .000 df = 256

The results in Table 3 demonstrate that the negative effect of intensive watching of violent TV drama is perceived as higher on others than on self among binge-watchers of violent US TV drama. The difference is significant. The second hypothesis is therefore accepted.

H3: Binge-watchers of US TV dramas who perceive that it negatively affects others more than themselves are more likely to support imposing censorship.

Pearson correlation was used to examine this hypothesis.

Table 4. Correlation between TPE behavioral (censorship) and perceptual component

| Pearson correlation | US drama | US violent |

| On self | .068 NS | -.235 ** |

| On others | .168 * | .128 *** |

* P<.01 ** p<.000 *** P<.05 (NS) Not significant

The results in Table 4 indicate a positive, significant correlation between the perception of the negative impact of binge-watching of US drama on others and the support of censoring US drama (r = .168, P< .001) and US violent drama (r= .128, P<.05).

There is no significant correlation between the perception of the negative effect of binge-watching US drama on self and the support of censorship. The correlation was significant between the perception of the negative effect of violent US drama on self and censorship (r= -.235, p<.05). This indicates that binge-watchers of violent US drama do not support censoring US violent drama, which they perceive as having a negative effect on others, but not themselves.

H4: Cultural background (individualism vs collectivism) of binge-watchers of US drama correlates to the perception of its negative effect on self vs. others.

The mean and standard deviation of individualism and collectivism statements based on the respondents’ answers were measured (Table 5).

Table 5. Levels of individualism & collectivism among Arab residence of UAE (n=257)*

| Mean | St. D. | |

| Individualism | ||

| · I should decide my future on my own | 4.18 | .993 |

| · My identity is very important to me | 4.34 | .979 |

| · I take responsibility for my actions | 4.21 | 1.146 |

| · I try not to depend on others | 3.92 | 1.144 |

| · What happens to me is my own doing | 3.72 | 1.185 |

| · I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others | 4.20 | .995 |

| · I enjoy being unique and different from others | 4.10 | 1.069 |

| · I am a unique personality separate from others | 4.02 | 1.114 |

| · I should be judged on my own merit | 4.24 | 1.040 |

| · I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards | 4.33 | .949 |

| · I try to avoid customs and conventions | 3.29 | 1.214 |

| · I don't support a group decision when it is wrong | 4.15 | 1.087 |

| · If there is a conflict between my values and the values of groups of which I am a member, I follow my values.

· The overall score of individualism |

3.84

4.04 |

1.120 |

| Mean | St. D. | |

| Collectivism | ||

| · I respect the majority's wishes in groups of which I am a member | 4.08 | .951 |

| · I maintain harmony in the groups of which I am a member | 4.08 | .908 |

| · I respect decisions made by my group | 4.17 | .898 |

| · I consult with other students on work-related matters | 3.72 | 1.074 |

| · I give special consideration to others' personal situations so I can be efficient at work | 3.85 | 1.001 |

| · I stick with my group even through difficulties | 4.26 | .950 |

| · It is better to consult with others and get their opinions before doing anything | 3.97 | 1.055 |

| · I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group | 3.40 | 1.162 |

| · It is important to consult close friends and get their ideas before making a decision. | 3.80 | 1.007 |

| · I help acquaintances, even if it is inconvenient | 4.06 | .952 |

| · I will stay in a group if they need me, even when I’m not happy with the group | 3.63 | 1.172 |

| · I consult with others before making important decisions | 3.88 | .995 |

| · My relationships with others are more important than my accomplishments | 3.60

|

1.135 |

Overall score of collectivism 4.19

*Agreement of each statement was measured on a 5-point scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree.

As shown in Table 5, respondents tend to get a higher mean score in collectivism (interdependency) rather than individualism (independency), with a small difference in the overall average mean score of (4.04) for individualism compared to (4.19) for collectivism.

The highest agreement on the independency scale was found in the statements: “My identity is very important to me” (4.34); “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards” (4.33); “I should be judged on my merit” (4.24); “I take responsibility for my actions” (4.21); “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others” (4.20); “I should decide my future on my own” (4.18); and “I don't support a group decision when it is wrong” (4.15). As for the collectivism statements (interdependency), the strongest statements were for: “ I stick with my group even through difficulties” (4.26); “I respect decisions made by my group” (4.17); “I respect the majority's wishes in groups of which I am a member” (4.08); “I maintain harmony in the groups of which I am a member” (4.08) and “I help acquaintances, even if it is inconvenient” (4.06).

To test H4, Pearson correlation was used. The results showed that the respondents’ cultural background (individualism vs. collectivism) does not affect binge US drama watcher’s perception of its negative effects, neither on self nor others. This means that the perception of the negative effect of US drama and its violent content is not affected by the individuals’ perception of cultural self-construal, whether individualist or collectivist. This means that H4 is not accepted as the cultural self-construal was not proven to be a predictive factor of TPE.

H5: The third-person effect differs among binge US drama watchers according to their age, gender, English language proficiency, and visit(s) to the USA.

A T-test was used to examine this hypothesis. Results revealed that the gender and age of binge-watchers do not make a significant difference in the perception of the negative effect of US drama on self vs. others.

Pearson correlation revealed a non-significant negative correlation between the English language proficiency of respondents and the TPE in relation to the perception of the negative effect of US drama and violent drama on self vs. others.

As for the number of visits to the USA, the Pearson correlation revealed a significant negative correlation (r = -0.161, P< .01) between the perception of the negative effect of US drama and violent drama on self vs. others. The results also revealed that the correlation was not significant between the US visit and perception of the negative effect of US drama. Accordingly, visiting the USA can be considered a variable useful for predicting the perception of the negative effects of US drama on self and others. Therefore, the H5 is partially accepted.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study investigated the relationship between binge-watching of televised US drama and violent drama on self vs. others. It also examined the role of cultural self-construal on the perceptual and behavioral components of TPE. Age, gender, English language proficiency, and the number of visits to the USA were examined as control variables.

The results showed that 96.6% of US drama binge-watchers prefer watching violent US drama. This finding is consistent with prior studies (Ahmed 2017, 2019) showing that Emiratis and UAE Arab residents tend to binge-watch foreign and US drama more than other types of TV content. The preference for US drama, especially violent drama, raises fears of possible negative impacts of its content on the cultural values of Arab youth. As predicted, binger US drama watchers tend to perceive the effect of US drama and violent drama to be positive for self, while they found US drama to be negative for other Arab youth. Consequently, they support censorship on the flow and content of US drama in Arab countries.

The perception of a negative effect of US drama on others is consistent with other findings of previous research on the negative effect of US media content on the culture and values in other Muslim countries, such as Indonesia (Wallnat et al. 2002) and Malaysia (Wallnat et al. 2007). In the same context, Sun, Shen, and Pan (2008) concluded that attaching greater negative implications to reality TV shows was related to a greater likelihood of engaging in corrective behaviors. By contrast, Willnat et al. 2002 found that Asian and European students with higher levels of US movie exposure tend to exhibit smaller third-person effects. They were less likely to believe that US media affected the cultural values of others more than their own.

The research findings revealed that the respondents tend to perceive themselves as collectivist (mean 4.19) rather than individualist (mean 4.02); despite the high mean score of most of the individualist statements. This indicates how binge US drama watching might affect the cultural structure and identity of Arab youth that used to be more interdependent rather than independent in nature. The current research hypothesized that this difference in perception of the negative effect of US drama on self and others might be related to the perception of cultural self-construal. The results showed that the assumption that there is a difference between self and others in the perception of the harmful effects of US TV drama might be consistent with collectivist more than individualist cultural self-construal, but the correlation was not significant.

Similarly, Willnat et al., (2007) found that the differences in perception between the two groups (individualist and collectivist) were not significant. However, respondents who exhibit an interdependent self-construal were less likely to exhibit TPE and more likely to support censorship of US drama in Malaysia, unlike in the current study where no relationship was found between the two groups and the support of censorship.

While age and gender do not have a significant effect on US drama binge-watching and the third-person effect, the results revealed that the more respondents visited the USA, the less they perceived the harmful effect of US drama and its violent content on self and others. However, English language proficiency did not have a significant effect.

The overall results of the study support the perceptual and behavioral hypotheses of TPE, while the cultural background of respondents did not affect the relation between TPE and binge-watching of US drama and violent drama.

Ahmed (2021) explained that examining TV binge-watching with the third-person effect approach provides significant insights into the perception of the effects of binge-watching US drama. If a person perceives that the negative effects of US drama are higher on others than self, s/he will resume binge-watching, while denying these effects on his/her cultural identity. Consequently, the tendency of Arab youth to consume the US televised media production will continue to grow.

Limitations and Future Research

The findings cannot be generalized to the whole population due to the sample size and non-probability sampling technique. However, the study provides a significant indication of the hypothesized correlations regarding the validity of the perceptual and behavioral components of the third-person effect theory. Further studies with extended probability sample size are recommended in order to investigate binge-watching and TPE, in which they could also consider other control variables such as education level.

Further research should investigate the possible causes of TPE, such as attribution error, self-serving bias, and biased optimism (Griffin 2009). The possible impact of other variables also should be studied, for example, psychological proximity; which is the psychological distance between an individual and others.

More research should study the impact of foreign media content flow to Middle East countries and the tendency of Arab and Muslim youth to consume US media content compared to the consumption of Arab media and televised production. Media imperialism should continue to be investigated in light of its novel forms made possible by new technologies and the availability of media content through these technologies. The influence of US and European media content on cultural identity requires further attention. Possible effects of binge-watching are still an evolving interdisciplinary research area that needs more focus from media and psychology scholars.

This research was funded by the Zayed University Office of Research 2019

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub