Issue 25, winter/spring 2018

https://doi.org/10.70090/KDCW18VF

Abstract

The rise of ideologically-driven lone actor terrorist attacks, coupled with the use of Internet-circulated media products as sources of inspiration, raises the need to understand the message strategies embedded in media campaigns of groups like ISIS. To better understand “enforcers” of ISIS’ interpretation of Shari’a law on the global stage, this study examines how ISIS has visualized law enforcement in its claimed territories in Iraq, Syria, and other Arab countries in the online publication, Dabiq, since the declaration of the so-called caliphate. Using a quantitative content analysis and a qualitative visual framing analysis of all law enforcement-related images in the fifteen issues of Dabiq, the study identifies four law enforcement frames and examines Entman’s framing associations—the problem definition, causes, moral stance, and treatment recommendations—displayed in each frame.

Introduction

Lone actor attacks pose a daunting challenge to governments worldwide and the communities they serve. Such attacks are on the rise (Gill, Horgan, and Deckert 2013) and often serve as disturbing content for stories distributed by global media operations (Ahram Online 2017; Ellis et al. 2016). Lone actors now rely more heavily on the use of explosive devices (Becker 2014), and produce significantly higher fatality rates when ideology motivates their attacks (Capellan 2015).

One specific type of lone actor that has become a growing matter of international concern is the vigilante who “enforces” ISIS or Daesh’s interpretations of Shari’a law[1]. In 2014, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported an ISIS penal code document surfaced from ar-Raqqa, which listed eleven offenses punishable by killings, beheadings, stoning, hand cuttings, or lashes, depending on the crime. The code specified eleven offenses: Insulting Allah, Prophet Muhammad, or Islam as well as adultery, homosexuality, stealing, drinking alcohol, slander, spying, apostatizing, and banditry (CNN Arabic 2015). Reiteration of similar interpretations of Shari’a has appeared in ISIS leaflets (e.g., Al-Himma Library, 2016) and, more recently, in several issues of the group’s latest online magazine, Rumiyah (Al-Hayat Media Center 2016a; Al-Hayat Media Center 2016b; Al-Hayat Media Center 2017; Al-Bengali 2016).

Lone actor attacks motivated by the enforcement of some kind of a penal code are increasingly commonplace on the global stage. A few recent examples illustrate this point: In Alexandria, a 48-year old man beheaded a Christian liquor shop owner for selling alcohol. In Istanbul, a gunman killed 39 people in a nightclub who were celebrating New Year festivities. In Paris, two brothers shot up the offices of Charlie Hebdo in response to the lampooning of Prophet Muhammad in the publication’s cartoons. In Copenhagen, a lone gunman attacked a café during a free speech seminar with Lars Vilks, who had previously ridiculed the Prophet in his drawings. In Orlando, 49 individuals lost their lives when a lone gunman attacked them in a gay nightclub. In upstate New York, a self-radicalized, online ISIS follower plotted a foiled New Year’s Eve attack on a bar that was planning to serve craft beer in celebration. In Germany, a man blew himself up outside of a wine bar, injuring fifteen customers.

Recognizing that differing definitions of “lone wolves” have keen implications for discerning effective response options, scholars have begun to examine the conceptual confusion present in early lone actor studies and create classificatory schema for better understanding the phenomenon (Becker 2016; Lankford 2013; Pantucci 2011; Simon 2013; Spaaij and Hamm 2015). While the scholarly move to disaggregate lone actors based on number of participants, motivations, and organizational hierarchies has value for developing more refined programs of deterrence, disaggregating extremist and militant groups’ media campaigns will also make a needed contribution to such efforts.

Prior research demonstrates that online content is a key factor in lone actor attacks. Interviews with radicalized individuals indicate the Internet serves as “a key source of information, communication, and of propaganda for their extremist beliefs. . . [and provides] greater opportunity than offline interactions to confirm existing beliefs” (Behr et al. 2013, p. xi). Further, as many as 77% of ideological active lone shooters become “self-radicalized through Internet forums and other forms of media, such as music, books, and magazines,” (Capellan 2015, p. 407; Gill and Corner 2015) with half learning their attack method online (Gill, Horgan, and Deckert 2013). Statistical analyses of UK attackers conclude those who focus on hard targets, those willing to use IED explosives, and those engaged in lone actor attacks show significantly higher levels of online learning than other extremist offenders (Gill et al. 2017). Law enforcement agencies have also found traces of militant groups’ propaganda videos, publications, and instruction manuals on lone actors’ computers and devices (Behr et al. 2013). More recently, police found 90 videos and almost 4000 images on the ISIS-inspired lone actor who carried out the Manhattan truck attack (Chavez and Levenson 2017).

To better understand what ISIS-inspired lone actors see online, this study examines ISIS’s media strategies related to the portrayal of Shari’a law enforcement in Dabiq, the group’s online magazine that surfaced in July 2014 for two years after the self-declaration of the caliphate. Building on what Anderson (2006), Stegler, (2008), and Taylor (2002) recognize as various types of imagined communities, this study identifies visual strategies ISIS used to create and define the community boundaries of the self-declared caliphate in its first two years. The analysis ascertains what ISIS depicts as unacceptable behaviors, as well as the appropriate punishments for such offenses.

ISIS’s Law Enforcement Context

Since its inception, law enforcement has consistently served as a key component of ISIS’s governance. Reportedly operating as a mafia organization in cities like Mosul in 2006 (Al-Tamimi 2015b), ISIS began presenting itself as a state that enforced Shari’a law. Despite setbacks between 2007 and 2009 due to the surge of U.S. forces in Iraq and the collaborating local tribes (McCants 2015), ISIS worked to implement an image of Islamic statehood by distributing videos announcing two cabinets of ministers, each with an identified minister of Shari’a (Al-Furqan Media 2007; Al-Furqan Media 2009). By the beginning of 2014, the Syrian civil war allowed ISIS to boost its “rule of Shari’a” image by establishing Islamic courts in the areas of Syria and Iraq under its control (McCants 2015; Al-Tamimi 2015a). These courts licensed marriages and received civilian complaints as a way to create some semblance of order (Hassan and McCants 2016; Al-Tamimi 2015b; Revkin 2016).

As ISIS announced its so-called caliphate in 2014, the group’s law enforcement pursuits proliferated. Shari’a institutes appeared, along with hisba[2] activities and hudud[3] punishments, including executions, stoning, cutting hands, and lashings (Al-Tamimi 2015a). ISIS created a Ministry of Hisba and another for Judiciary and Complaints, which together standardized laws and regulations across the group’s territories in Iraq and Syria (Al-Tamimi 2015b). Eventually, ISIS’s evolution of law enforcement capacities grew beyond its strongholds to reach Libya for a period of time (Zelin 2016). Viewed as a whole, ISIS’s law enforcement activities have functioned to help establish the group’s vision of an Islamic state for over a decade.

Revisiting Studies of ISIS’s Media Campaign

This analysis of ISIS media portrayals of law enforcement contributes to existing understandings of the group’s media campaign in three ways. First, the study yields insights into how ISIS uses depictions of law enforcement to create community norms. To date, most of the work examining the relationship between media products and ISIS’s law enforcement practices generally focuses on Western media portrayals of ISIS’s executions (Friis 2015; Smith et al. 2016), with only a limited number of studies determining how ISIS’s media campaign depicts law enforcement. These studies intermittently cast ISIS’s law enforcement activities into a wide range of overlapping taxonomies, including extrajudicial executions, brutality, hisba, and utopia. Winter (2015), for example, situates confiscation of cigarettes and hudud punishments for civil/religious crimes as part of a utopia frame and executions of local alleged spies/foreigners under a brutality frame, thereby diluting more specific findings regarding how ISIS presents law enforcement. Zelin (2015) employs a holistic examination of ISIS’s law enforcement actions by including executions, hudud punishments, and burning of cigarettes under one hisba frame, but only examines one week of the group’s media products. Tinnes (2016) describes all ISIS’s law enforcement practices as extra-judicial executions, which sidesteps how those same activities function within the group’s global community-building agenda. No previous study has conducted a multi-year, systematic study of ISIS media strategies for understanding the group’s interpretation of Shari’a law.

Second, this study adds to previous understandings of the media strategies deployed in Dabiq. Readily accessible to global audiences through a simple Google search, Dabiq remains a lasting tool of inspiration for members of the virtual caliphate and a window on how a caliphate did and should operate. Although national and international media outlets have provided widespread coverage to Dabiq, scholarly analyses are more limited. Those examining the magazine’s textual strategies focus on enemy portrayals, use of apocalyptic narratives, evolution of language strategies, and depictions of in- and out-groups (El-Badawy, Comerford, and Welby 2015; Gambhir 2014; Ingram 2016a; Kuznar 2015; Siboni, Cohen, and Koren 2015; Tome 2015; Vergani and Bliuc 2015; Wilgenburg 2015). No earlier studies of Dabiq systematically examine how the magazine presents ISIS’s Shari’a law enforcement.

Finally, the study provides a greater understanding of ISIS’s visual messaging strategies in Dabiq, which relies heavily on visual images to communicate its messages, using an average of almost 100 images per issue. Visual messaging strategies warrant independent examination, as they are less intrusive than text, require less cognitive load and imply truth to viewers (Messaris and Abraham 2001; Wischmann 1987; Rodriguez and Dimitrova 2011). To date, however, the work on visual images in Dabiq only analyzes the magazine’s figurative representations of humans, high production quality, resemblance to al-Qaeda’s Inspire magazine or ISIS’s recent magazine Rumiyah, thematic grouping of images by frame, and the use of the Western about-to-die trope (Damanhoury 2016; Fahmy 2016a; Fahmy 2016b; Furedi 2016; Kovacs 2015; Winkler et al. 2016; Wignell et al. 2017). Visual displays of law enforcement practices remain generally unexplored, despite findings of earlier studies that extensive viewing of law enforcement coverage in other contexts results in audiences becoming more fearful (Ghanem 1996; Holbert, Shah, and Kwak 2004; Romer, Jamieson, and Aday 2003; Schlesinger, Tumber, and Murdock 1991). Hence, this study attempts to answer two main research questions:

RQ1: How did ISIS visually frame its law enforcement capabilities as a self-declared state in Dabiq?

RQ2: How did ISIS photographers and photo editors use visual semiotics in their depiction of law enforcement activities in Dabiq?

A Multi-Pronged Method of Analysis

To better understand how ISIS portrays law enforcement within its media campaign, this study employed a two-stage process: A quantitative content analysis to examine visual semiotics (i.e. perceived distance, camera angle, eye contact, and facial expressions, etc..), followed by a qualitative visual framing analysis to examine the recurring visual themes. First, the authors conducted a content analysis of the 1475 images displayed in Dabiq’s fifteen issues (distributed between July 2014 and July 2016). Based on initial observations of the magazine, the authors developed a coding instrument and three coders conducted a pilot test on the first issue. After revising the coding categories for inter-coder reliability, mutually agreed upon oral and written instructions guided all coders. In the final analysis, a third coder resolved discrepancies in cases where the first two coders disagreed. Using Cohen’s Kappa, the average inter-coder reliability score was 91.4 across all relevant variables (see Table 1). The coders examined the number of humans serving as photo subjects, age, gender, stance, facial expressions, and eye contact, as direct eye contact, in particular, contributes to the establishment of connections with viewers (Kress and van Leeuwen 1996). The coding instrument also assessed other aspects of the visual semiotics, such as camera angles, as viewer position conveys visual parity/equality when shot at eye-level with photo subject, inferiority when the camera is looking down on the photo subject, and relative power, dominance, and credibility when the camera is looking up to the photo subject (Fahmy 2004; Kraft 1987; Mandell and Shaw 1973; McCain, Chilberg, and Wakshlag 1977). They also assessed perceived distance to the photo subject, as intimate and personal distances convey a close personal connection, while farther social or public distances treat photo subjects “as types rather than as individuals” (Jewitt and Oyama 2008, p. 146; Lombard and Ditton 1997; Kress and van Leeuwen 1996).

| Variable | Percent Agreement | Cohen’s Kappa |

| Law Enforcement | 92.5% | 0.88 |

| Size | 98.4% | 0.95 |

| Page Position | 98.6% | 0.96 |

| Distance | 89.9% | 0.86 |

| Viewer Position | 92.7% | 0.84 |

| Eye Contact | 98.5% | 0.96 |

| About to Die Image Type | 96.8% | 0.94 |

| Facial Expressions | 92.5% | 0.90 |

| Stance | 97.2% | 0.90 |

| Age | 95.4% | 0.93 |

| Gender | 96.9% | 0.95 |

| Number of Humans | 94.4% | 0.90 |

Table 1: Inter-Coder Reliability of Dabiq Coding Instrument

Second, the study employed an inductive approach in its choice of visual frames, which allows alternative frames to emerge from the analysis (Vreese 2005). After analyzing the images to identify recurring law enforcement themes, four main visual frames emerged: Local enemy fighters, crusader coalition, hudud implementation, and threat prevention. The authors then utilized Entman’s (1993) concept of framing to examine “problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (p. 52) displayed in law enforcement images. The framing analysis considered both visual semiotics and content factors in the magazine’s images, in ways similar to previous studies (Fahmy 2004; Parry 2011). Borrowing from Patridge (2005), the analysis examined textual information from photo captions and headlines to determine variables not visually explicit.

As this analysis will show, law enforcement images do form a visual imaginary for how ISIS’s global caliphate can and should abide by Shari’a law and provide a ready-made visual guidebook for potential followers. ISIS’s law enforcement images, however, do not produce a homogenous set of guidelines for control under Shari’a law. Instead, the group’s depictions of four distinct law enforcement frames each display a unique constellation of visual characteristics.

Dabiq’s Imaging of Law Enforcement

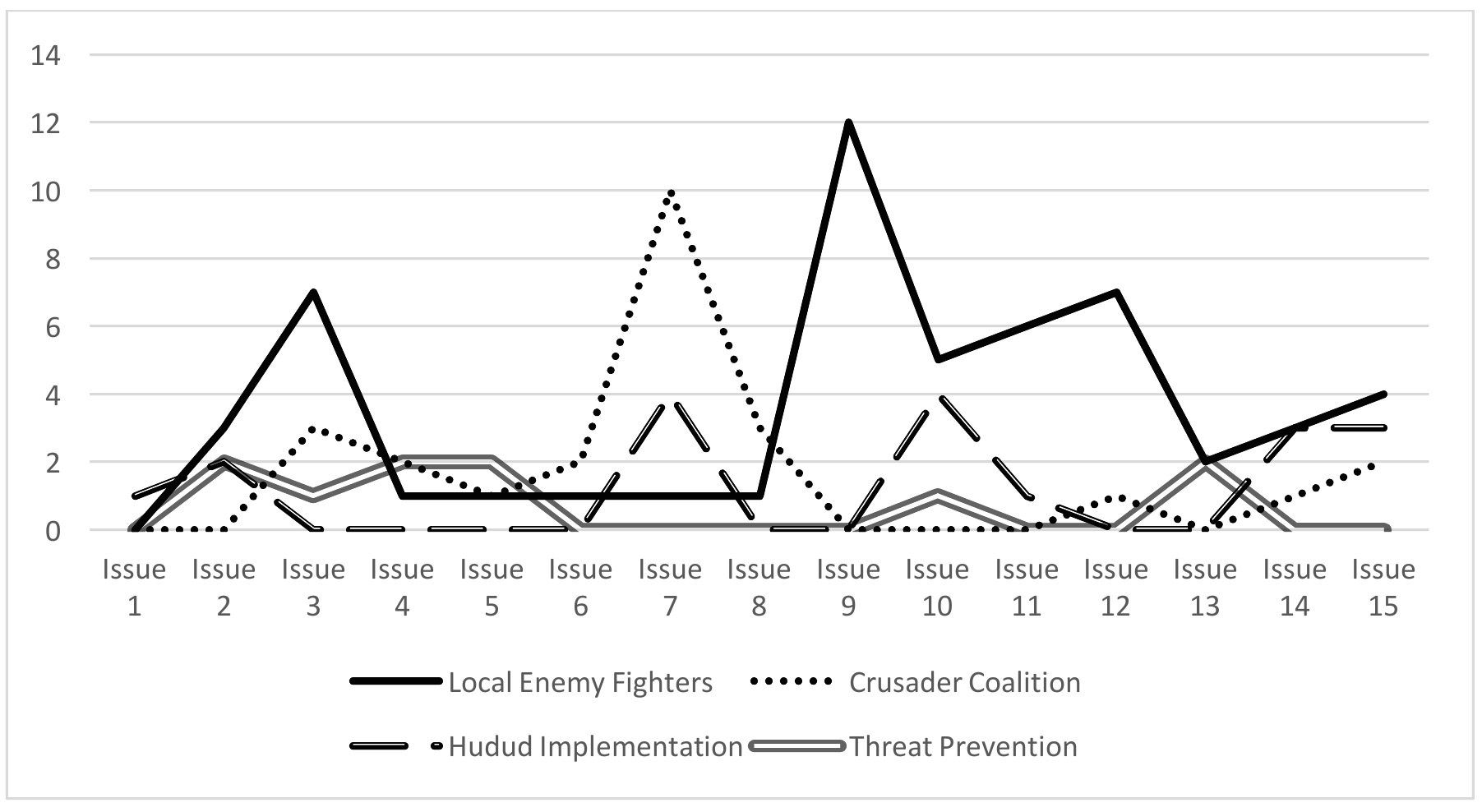

One hundred and seven images, or 7% of all Dabiq photographs, display an act of law enforcement. Over the course of the magazine’s history, Dabiq shifts the level of emphasis it places on law enforcement. Issue 9 (released May 2015) serves as a key turning point for the change, as the magazine introduces a new feature, “Selected 10,” which in its 22 subsequent iterations, visualizes life in ISIS territories through screenshots from the top 10 videos produced in ISIS provinces. Accordingly, the total number of law enforcement images increases from an average of six per issue in the first eight issues to nearly eight per issue in the last seven (see Figure 1), with over one-third of the total number of law enforcement images appearing in the “Selected 10” sections of the last seven issues.

Forty-five of the 107 law enforcement images (42%) feature explicit examples of the offenses and punishments identified in the ar-Raqqa penal code document. In rank order of appearance, the displayed offenses are apostasy/collusion (14), spying (11), adultery/fornication (5), homosexuality (5), drinking alcohol (4), stealing (2), banditry (2), and insulting the Messenger (2). Image captions explicitly identifying individuals accused of insulting Allah, insulting the Islamic religion, or committing slander, do not appear in Dabiq. Other law enforcement images lack explicit mention of the crimes listed in the penal code, but still relate when the broader content of Dabiq receives consideration. For example, labels such as “Rafidi” soldiers (a derogatory term referring to Shiites) and “Nusayri” soldiers (a derogatory term referring to the Alawite Syrian regime) appear as examples of apostasy, based on magazine content displayed elsewhere in the same issues identifying those two groups as local fighters that have turned their backs on Islam.

Taken as a whole, the law enforcement images in Dabiq fall within four visual frames: local enemy fighters, crusader coalition, hudud implementation, and threat prevention. Each frame promotes a unique constellation of elements related to problem definition, causal interpretation, moral aspect, and treatment recommendations.

Figure 1: Number of Law Enforcement Frames per Dabiq issue

Local Enemy Fighters

The most frequently recurring visual frame associated with ISIS's interpretation of Shari’a law involves local enemy fighters. Fifty-four law enforcement images show local enemy fighters. The appearance of the frame becomes more frequent in the later issues of the magazine. Only 16 local enemy fighter images appear in Issues 1-7; the remaining 38 occur in Issues 8-15.

The two defined problems associated with local enemy fighters are spying for the enemy and serving as apostates who have turned their backs on Islam. Soldiers and officers defending states in close vicinity to ISIS controlled territories, as well as militants from groups fighting ISIS forces on the ground, qualify as local enemy fighters. Explicit captions associated with the photographs, the magazine’s depiction of certain state and group actors as enemies of ISIS, and the visual presentation of the prisoners in orange, red, or blue jumpsuits cue the viewer to recognize local enemy fighter groups who have violated Deash’s interpretation of Shari’a law.

Dabiq presents the primary causes of the local enemy problem to be those working and colluding with the Iraqi and Syrian regimes, the Shia militias, and the Peshmerga (Kurdish) soldiers. Less frequent, but still present, are images of soldiers, Houthis, and tribal members in Sinai, Yemen, Khurasan (Afghanistan/Pakistan), and Libya. Story titles and captions in Dabiq do not identify specific spies, traitors, or enemy soldiers within the local enemy fighter frame. Images in this category portray the individuals as representatives of an out-group, rather than as named individuals. For example, a three-page article entitled “The Punishing of Shu’aytat for Treachery” in Issue 3 includes five images showing the arrest and mass shooting of almost 20 members of the Shu’aytat tribe in Syria (Al-Hayat Media Center 2014a, p. 12). Dabiq bolsters such anonymity by using small images to portray local enemy fighters. Almost 90% of local enemy executions appear on less than half a page, with a full 65% appearing as video screengrabs within the smaller “Selected 10” images. The absence of any identifiers beyond group membership invites viewers to conclude that those associated with the represented out-group pose a threat to the ISIS community. The magazine’s visual strategy also addresses the potential for viewers themselves to become part of the cause by collaborating with local groups opposed to ISIS. Over two-thirds of local enemy fighter photographs encourage viewer parity with the captured soldier, fighter, or alleged spy by incorporating eye-level shots of the offender. A heavy reliance on photographs that capture the photo subject from a personal or intimate distance (i.e., less than four feet) encourages the close, personal connection with the individuals awaiting execution. By specifying the out-groups at risk and visualizing the dire consequences of serving as part of their group, Dabiq encourages viewers to respond by staying away from those enemies and their actions.

The moral aspect of the local enemy fighter frame involves the supremacy of ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a law over competing understandings. Dabiq visually associates the executions of local enemy fighters with Islam by incorporating a higher percentage of ISIS militants gesturing the sign of tawhid (with an index finger pointed to heaven indicating monotheism) than in the other law enforcement frames. The magazine emphasizes the superiority of ISIS’s interpretation by repeatedly depicting ISIS militants towering over predominately Muslim local enemy fighters, who often appear on their knees awaiting execution for spying or apostasy. The camera angles utilized in the local enemy fighter frame also work to reinforce the moral message. In local enemy fighter images where the camera tilts upward, the shots attempt to refer authority status, dominance, and agency on ISIS militants administering justice; when the camera tilts downward, the shots project a sense of inferiority and submissiveness on local Muslims facing pending or actuated executions (see Figure 2).

The treatment recommendation for addressing the local enemy fighter problem is direct killing of such offenders. Using examples consistent with punishments outlined in the ar-Raqqa penal code document referenced earlier, Dabiq illustrates that local enemy fighters should experience retributive justice, whether by shootings or beheadings. Individuals visually depicted as appropriate agents for administering justice are typically adult ISIS militiamen, but children assume the roles on occasion. In Issue 9, for example, a photograph shows a child militant, with a serious look on his face, holding his pistol ready to execute a kneeling prisoner with the accompanying headline, “The Lion Cubs of the Khilafah.” The photograph illustrates that viewers can anticipate enforcers of ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a law remaining far into the future (Al-Hayat Media Center 2015b, p. 21).

In sum, the local enemy fighter frame defines fighting ISIS and colluding with its enemies as acts of aggression and treachery, presents particular local groups as the primary cause for the needed law enforcement action, highlights the protection of the group’s interpretation of the Muslim faith as a moral goal, and recommends various forms of retribution through execution as the necessary treatment for such offenses.

Figure 2: Image looking down at a Syrian soldier before his execution in Issue 12

Crusader Coalition

The crusader coalition frame encompasses the second largest category of law enforcement images. Twenty-five law enforcement images show crusader-related enemies who, according to ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a law, are criminals. Dabiq’s emphasis on the crusader coalition frame is far more prominent in the earlier issues of the magazine during the group’s heydays before losing much of its territorial grounds. Sixteen crusader coalition images appear in the magazine’s first seven issues; only nine occur in Issues 8-15.

The definition of the problem posed in the crusader coalition frame is multifaceted. Pictured offenses include insulting Prophet Muhammad, spying on ISIS, serving as an apostate, attacking Muslim lands, and attending businesses frequented by homosexuals and/or serving alcohol. Visual cues identifying offenders include submissive prisoners mostly in orange or yellow jumpsuits, as well as the destructive aftermath of ISIS-inspired attacks on foreign soil.

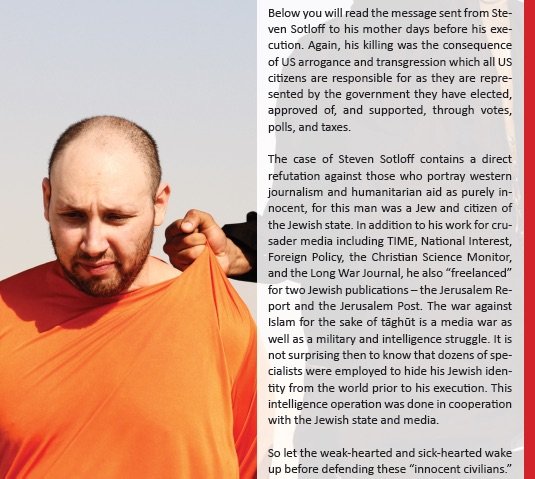

The key causes of the problem depicted in the crusader coalition frame are soldiers, officers, and civilians from countries that are members in or supportive of the U.S.-led coalition as opposed to ISIS. The offenders presented within the frame span the globe. They come from Japan, China, Norway, France, Belgium, the United States, Israel, and Jordan. In sharp contrast to the local enemy fighter frame, Dabiq often specifies the individual identity of the photo subjects in the crusader coalition photographs. The naming of British journalist John Cantlie, the Chinese freelance consultant Fan Jingui, and Norwegian Ole John Crimsgaard-Ofstad serve as illustrations. Beyond naming the identities of the offenders, Dabiq also often presents the crusader coalition participants as representatives of their home countries and/or the coalition. Captions, for example, identify Jordanian pilot Muaz al-Kasasbeh both as a representative of his country and the US-led coalition, Steven Sotloff and James Foley as representatives of the United States, and Muhammad Musallam, the alleged spy working for the Israeli national intelligence agency, Mossad, as a representative of Israel. By blurring the identities of individuals, countries, and coalition forces, ISIS widens the scope of parties it will hold responsible for violations of its guidelines.

Defining and explaining why members of the crusader coalition constitute the cause of the problem receives substantial attention in Dabiq. Four of the crusader coalition images cover a full page, including an image of James Foley on his knees in front of an ISIS militant beheading him, an image of a Mossad spy in an orange jumpsuit lying dead in front of a child militant, and another image depicting two Chinese and Norwegian prisoners lying dead after their executions (see Table 2). The magazine often provides accompanying articles and narrative-based photographic series to elaborate on how the offenders offend Shari’a law. A five-page article in Issue 4 serves to illustrate the approach. A series of nine images begin by showing Steven Sotloff in an orange jumpsuit on his knees looking down before his execution as an ISIS militant stands behind him holding the back of his jumpsuit (see Figure 3). Subsequent images show Sotloff’s Israeli passport, his mug shot, and him wearing a helmet and protective vest during past military operations. The next three images in the sequence show graphic images of the disfigured corpses of Iraqi women and children. Dabiq then presents a screengrab from a U.S. Department of Defense news release announcing the airstrikes before ending with a graphic image of Sotloff’s head lying on his torso after the beheading with the caption, “Sotloff was executed in retaliation for the numerous Muslims killed in Iraq by the US. American airstrikes.” (Al-Hayat Media Center 2014b, p. 51) While Dabiq typically concentrates the narrative of photo series in one issue, the magazine, at times, extends the captor’s fate across several issues, as evidenced by Foley’s appearance in Issue 3 and 14.

Similar to the depicted cause of the local enemy problem, the cause of the crusader coalition problem also allows for the possibility that the viewer may become part of the problem. More than half of the crusader coalition images are shot at eye-level, encouraging the viewer to closely connect with individuals undergoing execution. The vast majority of the images in the crusader coalition frame also show the offender all alone or accompanied only by an executioner, over half display the captive at an intimate or personal distance, and more than a third of the shots display the captive with a negative facial expression. Combined, the visual strategies render the crusader coalition frame disturbing, as the fateful consequences for viewers from coalition countries appear unmistakable.

The moral position of the crusader coalition frame stresses the supremacy of Islam over other competing religious faiths. As in the local enemy fighter frame, the camera angles in about a third of the images incorporating the crusader coalition frame look down at the captured or attacked offenders, suggesting the weakness or symbolic inferiority of individuals from other faiths and/or supporting the “crusaders.” Although the camera angle of two of the images in the crusader coalition frame point upward, the shots do not deviate from the frame’s standard message of control. One image looks up at the full body of a child militant holding his pistol after executing a Mossad spy who lies dead with the headline, “The Lions of Tomorrow” (Al-Hayat Media Center 2015a, p. 20). The image juxtaposes the symbolic power of the Muslim child with the inferiority and weakness of the spy. The second image appears in Issue 7, with a camera angle pointed upward towards a caged al-Kasasbeh’s face before his immolation (see Figure 4). Rather than connote authority, the combination of al-Kasasbeh’s facial close-up, his look of despair, his direct eye contact, his orange jumpsuit, and his positioning in a cage highlight his submissiveness and magnify fear of viewers or nations considering collaboration with the anti-ISIS coalition.

Figure 3: Image of Steven Sotloff before his beheading in Issue 4

Figure 4: Image looking up to Muaz al-Kasasbeh before his immolation in Issue 7

| Local Enemy Fighter | Crusader Coalition | Hudud Implementation | Threat Prevention | Total | |

| Full Image | 2 (4%)* | 4 (16%) | - | - | 6 |

| Half Page | 5 (9%) | 6 (24%) | 2 (11%) | 3 (30%) | 17 |

| <Half a Page | 47 (87%) | 15 (60%) | 16 (89%) | 7 (70%) | 85 |

| Total | 54 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 18 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 107 |

| *Percentages may not always appear to add up to 100 as they are rounded up. | |||||

Table 2: Size of Law Enforcement Images in Dabiq Magazine

The treatment recommendation Dabiq displays for the array of crimes present in the crusader coalition frame is singular: Execution. The specific form of the punishment typically ranges from shootings and beheadings, with one act of immolation. As in the case of the local enemy fighter frame, those qualified to carry out the punishments for violations of Shari’a law include not only adults, but also children.

Taken together, the crusader coalition frame defines the problem as many types of affronts to Islam both in ISIS-controlled territories and around the globe, identifies the cause of the problem to be coalition members, highlights ISIS’s role as a vanguard of Islam, and recommends indiscriminate, retributive killings as a necessary treatment.

Hudud Implementation

The third most frequently utilized frame to portray law enforcement in Dabiq concerns hudud implementation. Eighteen law enforcement images show practices of hudud implementation occurring within ISIS territories. These images appear more frequently in the later issues of Dabiq. Only four hudud images appear in issues 1-6, with the remaining 14 images displayed in issues 7-15.

The defined problems in the hudud frame are violations of the religious rules of daily life under Shari’a law as implemented in ISIS-claimed territories. The offenses include fornication, adultery, homosexuality, stealing, banditry, drinking alcohol, apostasy, collusion, and failure to pay taxes by non-Muslims. The hudud frame lacks the visual cues common in other Dabiq law enforcement frames, such as colorful jumpsuits, as offenders dress in every-day clothing. Those undergoing hudud punishment are treated as types rather than as named sinners, with 11 hudud punishment images shot at a social/public distance.

The causes of the problem in the hudud frame are individuals that succumb to temptations inconsistent with ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a law. Almost half of the images in the hudud frame focus on sex offenders. Five images focus on adulterers, two on homosexuals, and one on a man accused of fornication (see Table 3). Other hudud images show Christians in ISIS territories paying taxes for living under the protection of ISIS. Even children serve as part of the cause, suggesting that the problem will persist far into the future. One image in Issue 11, for example, shows two children sitting among a submissive Christian crowd gathered to pay taxes to an ISIS militant. Finally, as in the cases of the previous two Dabiq frames, viewers can also function as a potential cause of the problem identified in the hudud frame. Shot at the eye-level, 12 images prompt visual parity between the offender and the viewer and supply a warning for those who plan to act on perversions of the faith.

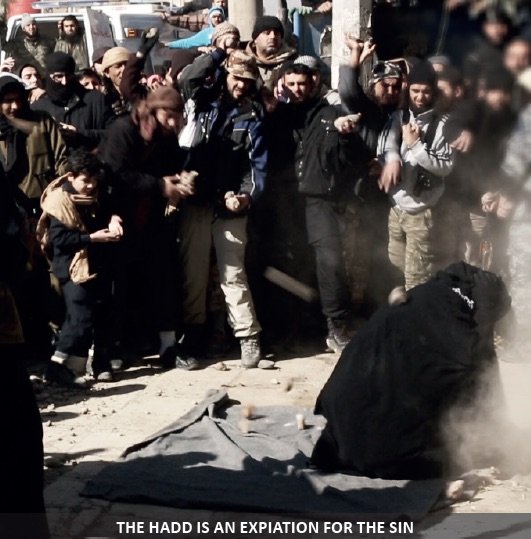

The moral position of the hudud frame stresses the need to establish and preserve a puritanical Islamic society. Dabiq visualizes the moral position of ISIS’s version of Shari’a law applied to everyday life by showing the enforced expiation for sinning. The magazine stresses the supremacy of ISIS’s punishments by using high camera angles that look down upon offenders in one third of the hudud images. Further, the body positions of ISIS militants and faithful members of the community implementing hudud also reinforce the higher moral position of ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a law. Offenders sit below an elevated stage when paying taxes, crouch on the ground while standing members of their communities stone them, look downward as they receive their lashings, and lay on the ground surrounded by standing members of the community after ISIS militants throw their bodies off buildings.

The recommended treatment for solving the problem in the hudud frame varies according to the severity of the offense committed. Dabiq shows those caught stealing having their hands cut off, those caught fornicating being lashed, those committing adultery being stoned, those identified as homosexuals being thrown off buildings, and those worshipping other faiths in the community having to pay taxes. Members of the ISIS-controlled community serve both as observers, shamers, and enforcers within the hudud frame. For example, the article “Clamping Down on Sexual Deviance” features four images in ar-Raqqah highlighting the punishments for homosexuality and adultery. To begin, an image shows a homosexual, who is blindfolded and sitting on a chair balanced on a ledge of a high building, with the caption, “A sodomite is thrown off a building in ar-Raqqah,” followed by a high angle shot from the building showing his dead body on the ground below surrounded by a large, observing crowd. Subsequently, a high angle shot shows a crowd participating in the stoning of a fully-covered woman, who is sitting on the ground and hiding her face for committing adultery with the caption, “Stoning a Zaniyah [adulterer] in ar-Raqqah,” followed by an image of the same woman photographed from a different angle showing her back with the crowd facing the camera and stoning her. Children actively participate in the treatment recommendations in Dabiq’s hudud frame. Two images show children among active community members engaged in stoning a woman for committing adultery (see Figure 5) or in attendance watching an ISIS militant beheading a sinner. The juxtaposition between the visual framing of Muslim children living in ISIS-controlled territories as contributors in the implementation of hudud punishments and Christian children as acquiescent participants in the cause suggest that agency flows from acceptance of the group and its interpretation of Islamic law.

Taken together, the hudud frame broadens the definition of a crime to include any deviations from ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a rules of behavior, presents individuals tempted to sin as prompting the need for hudud implementation in the society, highlights ISIS’s application of Shari’a to uphold a puritanical moral code, and recommends various forms of hudud punishments as necessary treatments dependent upon the nature of the offense.

Threat Prevention

The threat prevention frame encompasses the smallest number of law enforcement images in Dabiq. Only 10 images of the magazine’s law enforcement images, focus on threat prevention. Six of the threat prevention images appear in Issues 1-7; Dabiq displays the remaining four images in Issues 8-15, signalling no significant difference.

The defined problems in the threat prevention frame are substances that undermine the purity of the communities under ISIS’s control. The primary threats include cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs. All such substances serve as particular menaces for Muslim youth, but can also result in challenges for older members of the caliphate. Not only do the commodities carry health risks for heavy users, they also distract from the focused study of the Islamic faith and the need to defend the group without distraction. Photographs that display the implements of vice serve as the primary indicators of threat prevention frame.

Figure 5: Image of a crowd stoning a woman in ar-Raqqa for committing adultery in Issue 7

| Punishment Image | Frequency | Location |

| Stoning to death for adultery | 5 | Ar-Raqqah, Syria; one undisclosed |

| Throwing a Gay Man Off a Building | 2 | Ar-Raqqah, Syria |

| Imposing Jizyah on Christians | 2 | Ar-Raqqah; Aleppo, Syria |

| Cutting Hand for Theft | 2 | Ninawa, Iraq; Tarablus, Libya |

| Sharia Court | 2 | Ad-Dana, Syria; Tarablus, Libya |

| Lashing for Drinking Alcohol | 2 | Tarablus; Barqa, Libya |

| Shooting for Armed Robbery | 1 | Ar-Raqqah, Syria |

| Beheading by a Sword | 1 | Undisclosed |

| Lashing for Fornication | 1 | Unspecified |

Table 3: Type of Hudud Implementation Images in Dabiq Magazine

The cause of the problems related to cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs are either wayward individuals entering ISIS-controlled territories from the outside or fallen individuals within the ISIS community seeking to undermine it. Such threats divert those committed to ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a law by providing access to various forms of temptation.

The moral stance presented in the threat prevention frame is the assured, elevated status of a pure Muslim body. A total of eight threat prevention images position the impurities far away from the viewer, whether by distancing the hisba activity all together or placing only the hisba enforcers closer to the viewer. Two photographs showing the eradication of the disapproved substances further reinforce the moral positioning. Such images show hisba agents and other members of the community watching cigarettes and alcohol burn in a metaphorical reference to hell in the afterlife. The snapped shots of the eradication efforts appear at intimate or personal distance from the viewer, positioning the viewer to see the outcome that awaits the banned substances.

The treatment defined in the threat prevention frame involves preemptive, rather than corrective or punitive, action. Such solutions involve hisba, whereby its agents work to preserve the good by burning cartons of cigarettes, piles of drugs, and bottles of alcoholic beverages. In Issue 10, for example, an image shows three men in the brown hisba uniforms piling cigarettes and alcohol before burning them (see Figure 6). Appropriate treatments also include removing those who threaten ISIS communities by apprehending drug, alcohol, and cigarette traffickers and their offending wares at traffic checkpoints. The visual semiotics in the threat prevention frame, in particular, encourage viewer identification with individuals stopped at the traffic checkpoints as part of the treatment. By presenting the individuals stopped at checkpoints at eye-level with the viewer, the threat prevention frame seeks to instil fear in those considering the profit-making potential of supplying drugs, alcohol, or cigarettes in ISIS-controlled territories.

Taken together, the threat prevention frame defines the problem as various vices undermining the Muslim community, presents the traffickers of cigarettes, drugs, and alcohol as causes for corruption and impurity, highlights ISIS’s efforts to maintain a puritanical environment, and recommends hisba as a necessary treatment to alleviate the problem.

Figure 6: Image of hisba agents burning cigarettes and alcohol in Issue 10

Discussion and Conclusions

While ISIS replaced Dabiq with Rumiyah as its chief English language online periodical in August 2016 after the loss of territorial grounds due to intensified military pressure, Dabiq remains an accessible visual archive of law and order in the self-proclaimed caliphate at its peak. The law enforcement imagery in Dabiq depicts an institutionalized system of law enforcement practices that defines behavioral expectations for Deash’s interpretation of Shari’a law and establishes the respective normative consequences the group exacts for failure to abide by those parameters. By using visuals to make such limits explicit, the photographs in Dabiq offer insights for productively narrowing the likely range of targets for lone actors operating around the globe. The images depict the targeted country affiliations, group memberships, and individual behaviors that warrant a response. The depictions can also help predict the form of future attacks by outlining what ISIS considers appropriate and proportional responses for an array of offenses.

Considering Dabiq’s law and order images within the broader context of ISIS’s advertised penal codes for enforcing Shari’a law adds further capacity for narrowing, and perhaps foretelling, behaviors by the decisive minorities ISIS targets at the global stage. Our analysis cannot and does not intend to suggest a causal relationship between consuming Dabiq and lone actor attacks. However, studies have found empirical evidence for the role of the internet and online propaganda in learning and preparing for terror attacks in the US and Europe (Gill, Horgan, and Deckert 2013; Gill et al. 2017). What the study suggests is a key role for Dabiq’s law enforcement imagery in narrowing attacks by members of the decisive minorities, those who have a disproportionate influence (Ingram 2016b), by a motivation to uphold ISIS’s version of Shari’a law. Accordingly, at one level, identifying which offenses have yet to be featured in ISIS publications (i.e., committing slander and insulting Allah or the Islamic religion) arguably points to global activities ripe for sparking future attacks. At another, relative comparisons of Dabiq’s frequency of image use related to particular offenses is suggestive for what behaviors the group considers particularly troubling and worthy of immediate, punishing responses by global sympathizers.

ISIS’s interpretation of the form that such responses should take becomes evident in Dabiq’s presentation of its four law enforcement frames. The online, English-language magazine presents available treatment options that, in many ways, echo the historical implementation of the doctrine of manifest destiny by the United States. Just as American leaders employed a scaffolded strategy of assimilation, removal, and extermination to address the challenge of nation’s indigenous populations in the early days of the republic (Winkler, 2002) and to respond to those responsible for the 9/11 attacks (Winkler 2013), Dabiq’s law and order images display similar approaches for addressing the enemies of ISIS’s proclaimed caliphate. The magazine’s images utilizing the hudud frame feature assimilation, as corrective actions such as lashes and the cutting off of hands can render offenders rehabilitated and ready to re-join the ISIS community. Images in the threat prevention frame focus on removal, as hisba forces do not harbour illicit substances or those who traffic them to exist to within ISIS-controlled territories. Finally, images in the local enemy fighter and crusader coalition frames highlight extermination by displaying the executions of criminals who represent opposing groups near and far. Dabiq’s incorporation of manifest destiny strategies, steeped with both historical and contemporary resonance for English proficient audiences, has implications for lone actors wishing to punish those violating ISIS’s interpretation of Shari’a law.

The visual semiotics in the four image frames help reinforce the personal implications of choosing to become part of the cause or part of the treatment for offenses committed against Shari’a law. The repeated use of eye-level shots photographed from close personal distance in the local enemy fighter and crusader coalition frames reinforce that viewers can expect painful executions should they choose to fight or collude with those fighting against ISIS. By contrast, viewers also have the option of serving as part of the treatment, either by witnessing and shaming from a distance those who fall astray of the behavioral expectations of ISIS’s version of Shari’a law in the hudud frame or by observing the burning of illicit substances by hisba forces as part of the threat prevention frame.

During the period when ISIS fighters lost nearly half of the group’s controlled territory in Iraq and 20% of its territory in Syria (U.S. Department of Defense, 2016), Dabiq’s use of the four law enforcement frames was also changing. With increased military pressure on the group, the magazine has magnified its use of local enemy fighter and hudud images, perhaps in an effort to depict control over those in and around its immediate communities. The reduced use of the threat prevention and crusader coalition images is likely a function of the disruption of day-to-day operations in ISIS territories.

As the self-declared “Islamic Caliphate” continues to lose territory and retreat into the virtual realm, Dabiq remains an easily accessible visual guidebook for ISIS’s application of Shari’a law. Future studies could systematically examine imagery disseminated daily on ISIS’s official telegram channels, its local Arabic publication, al-Naba’, and its most recent long-form publication, Rumiyah. While Dabiq can serve as a benchmark for understanding the group’s emphasis on particular offenses and appropriate punishments, these other platforms will be key to understanding notable shifts in media strategy and their attendant consequences.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub