Issue 23, winter/spring 2017

https://doi.org/10.70090/CEK17SCF

This essay is part of an ethnographic study of Egyptian film production conducted between August 2013 and September 2015. The study is centered on participant observation within two main film companies, New Century Film Production and Al-Batrik Art Production, in addition to interviews conducted with key actors in the industry as well as all workers involved in two film projects, Décor (dir. Ahmad Abdalla, New Century, 2014) and Poisonous Roses (dir. Ahmad Fawzi Saleh, Al-Batrik, in postproduction). All interviews cited below have been conducted as part of this ethnographic study, which was aimed at examining the use of new media technologies by Egyptian filmmakers.

Scholars of media in the Middle East have tended to discuss state control over media production both as a formal and as an informal process. Formally, political and legal arrangements repress subversive narratives; informally, media producers are said to operate in a social and institutional environment where non-mainstream narratives are made unthinkable, leading to a form of self-censorship. This language of formality and informality is useful to describe the Egyptian state’s hold over film production, but it assumes a) that the source of control is some centralized agency and b) that the sphere beyond formal and informal state control is one of “freedom.” State control, however, is distributed over a number of institutions that cannot all be claimed to act at the behest of a central authority. Moreover, film production is always constrained by the kinds of factors designated by the label of “informal control.” Indeed, constraints over media content do not necessarily have to do with state intervention: they can arise by other means—e.g., when citizens interfere with film sets.

The assumption that “the state” can control media production is unsettled as soon as we consider the minutiae of issuing film permits in Egypt. This essay describes the interaction between Egyptian filmmakers, bureaucrats, and law enforcement officials in the process of issuing permits. Through this description, it argues that the idea of “state control” is visibly inadequate to account for the state’s peculiar social and material effects. To sustain this argument, the essay starts by giving a detailed description of existing permit-issuing rules in Egypt, going on to argue that the materiality of official letters and street politics can complicate our understanding of state control over Egyptian film production.

Issuing permits

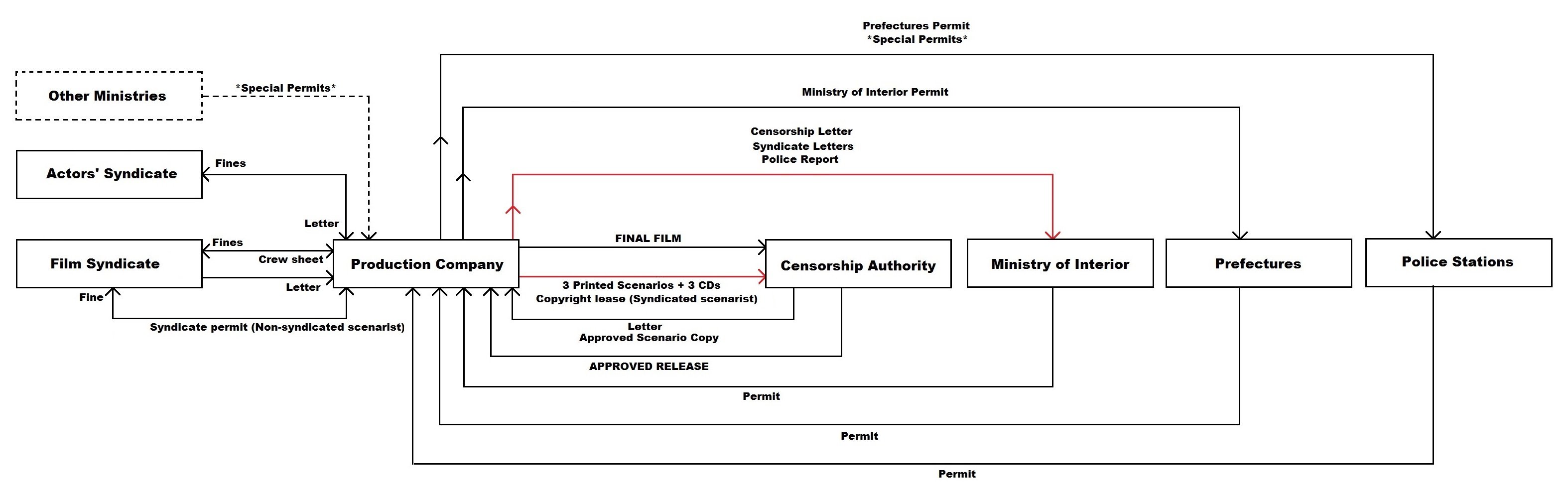

In principle, all external shooting in Egypt requires a permit from the Ministry of Interior. Ahmed Farghalli, a line producer, has traced a very useful diagram of the burdensome permit-issuing process (Figure 1). The history of this bureaucratic process is difficult to trace. In living memory, what Farghalli has described is recognized as the process through which media producers have always had to go in order to secure permits. One can still imagine that the permit-issuing burden has increased since the 1980s, with the growing reliance on external shooting locations in Egyptian cinema, as well as the increasing hold of Hosni Mubarak’s police state over the public domain.

[Figure 1 - For larger version, download PDF]

[Figure 1 - For larger version, download PDF]

The permit-issuing process starts when three scenarios are sent to the Censorship Authority with the screenwriter’s copyright lease. When the scenario is judged appropriate, the Authority issues an official letter to the Ministry of Interior and a sealed scenario copy. This copy needs to be produced to the Authority again, when the film is ready to be released. In principle, the film cannot contain any additional scenes to what was approved in the original scenario. In practice, however, the contingencies of filmmaking and the whims of individual censors make the correspondence between the initially approved scenario and the film a matter of case-by-case negotiation. The Censorship Authority, in short, has veto rights over any feature film at two stages: first, when a scenario is submitted before shooting; and second, when a film is submitted before theatrical release.

Following censorship approval, the two major state-sponsored syndicates concerned with the Egyptian film industry—the Cinematic Syndicate and the Actors’ Syndicate—need to issue some letters to obtain Ministry of Interior permits. The Cinematic Syndicate produces a work sheet with all crewmembers contracted on a project, while the Actors’ Syndicate produces a letter with all contracted cast members. The work sheet and the cast sheet only include syndicated workers: non-syndicated workers need a special permit in order to be included on the sheet. This comes at the cost of a fine, and the price of the fine is determined by implicit norms. According to Mohammed Hosny, an accountant in New Century, a project with a major movie star like Ahmad el-Saka will be fined more heavily than a project with a younger cast and crew, even when the number of non-syndicated workers is identical.[1] This is why membership in the relevant syndicate is encouraged by production companies, in order to avoid paying hefty fines.

Once syndicate work sheets are complete, and once all fines are paid, the Cinematic Syndicate and the Actors’ Syndicate issue a letter to the Ministry of Interior. This letter is sent to the Ministry with the Censorship Authority’s letter, a letter listing all external shooting locations in the film, and a police declaration, where the company certifies that the film will in no way impinge on police or army functions. With these papers in hand, the Ministry of Interior issues a permit addressed to the governorates, either to Cairo, Giza, or “Other Provinces.” This permit is used, in each province, to get a second permit from the Prefecture (mudiriyat al-amn). This permit is in turn given to the police department where one is intent on shooting, with a more specific list of shooting locations and dates in the area administered by the department. The same nested process occurs in each province: the Ministry of Interior permit is used to get a Prefecture permit which, in cases of external shooting, is used to get a police department permit. In areas administered by the Border Guards or Military Intelligence, including all Egyptian coasts and the national airspace, a special permit needs to be issued by the appropriate authority. The Ministry of Antiquities, the Ministry of Islamic Endowments, or the Ministry of Tourism will also issue special permits for the sites that they administer (e.g., the Pyramids, the Sultan Hassan Mosque, the Marriott Hotel in Zamalek). These special permits are addressed to the appropriate police department, where it is sent with appropriate Ministry and Prefecture permits.

Without all these permits, one is not legally allowed to shoot in external locations. Given the burdensomeness of issuing permits, several documentarians and low-budget productions shoot without permits, even though they remain liable to interruptions by local policemen and residents. Since larger movie productions are unwilling to take this risk, they tend to abide by existing permit-issuing rules. With this great bureaucratic burden, one can easily imagine why larger companies have workers who specialize in securing permits. These workers are sometimes known as mikhallaāti, or “the one who finishes [paperwork].” They are usually the ones doing all the legwork to carry the right set of papers from one institution to the next. They tend to be knowledgeable about the specific individuals that will sign the paperwork in each institution, and they tend to know which “gifts” (ikramiyāt) are required by each bureaucrat. These gifts are sometimes significant enough to be budgeted into a movie’s overall expenditures. Paperwork, then, is never simply deposited at an anonymous office until it is signed by some institutional mechanism. The permit-seeking worker literally has to run after the signatory, in person, partly to reinforce nepotistic links, but mostly to accelerate the overall process, which would take an inordinate amount of time if it were to simply hinge on a bureaucrat’s willingness to sign.

While permits are issued by many state institutions, their issuing involves the same basic operation: writing letters. This may seem like an exercise in individual composition, but writing letters is an activity governed by a stringent ideology of officialdom, which is shared by experienced production crewmembers and bureaucratic institutions alike (e.g., the Censorship Authority, the Ministry of Interior, the Prefectures).

This ideology constrains the wording of the letter. In some cases, the wording needs to conform to the institution’s exact demands if the letter is to be considered valid. During the preparations of Qut wa-Far (The Cat and the Mouse, dir. Tamer Mohsen, prod. New Century, 2015), the location manager Mohammed Setohy asked me to type a letter addressed to the head of the Egyptian Media Production City (EMPC), the largest state-owned multimedia compound in Egypt. Setohy would carefully verify every single word on screen, to make sure that the typed letter exactly conformed to the handwritten wording he had in hand. Khaled Adam, a production manager sitting nearby, asked Setohy whether the wording had changed. Setohy explained that the usual wording had to be changed to conform to the new EMPC administration’s exact demands.[2] As an aside, Adam explained that he used to handle permits in his production team, so he had to learn all the different wordings in different letters addressed to different institutions. After the 2013 military coup, political turmoil had spurred the EMPC to increase administrative control over access to their studios in conjunction with military restrictions over physical access to the site. Thus, without the correct letter wording, and without the EMPC’s permission, it would be next to impossible to gain access to the studios.

Further, this ideology of officialdom involves specific physical signs, such as the conventional arrangement of letter pages. Although letters are typed on computer, they need to be printed and signed by hand in order to be efficacious in state institutions. The letter described above started with a heading destined to the head of EMPC and went on to state some formulaic greeting, the film title with the director’s and the stars’ name, a list of equipment to be brought inside the EMPC, and a list of shooting locations inside the EMPC. It was signed by the line producer, whose physical signature is vital to establish the letter’s efficacy. This concern with signatures parallels a widespread concern with the clarity of government seals on official letters—a concern which is will be immediately understood by anyone who has dealt with the Egyptian bureaucracy. A letter may have the best wording and format, yet a faint seal may elicit suspicions on the part of officials who are enforcing the document’s legality, even if the document was produced by another government agency. Given these concerns, the tightly governed wording of the letter matters as much as its meaning and physical presence.

Permits on Set

Once permits are issued, their presence on set is necessary to convince the police or inquisitive citizens that the shooting is legal. This is crucial to avoid costly delays in shooting. For example, while shooting in a building overlooking the iconic Tahrir Square in 2014, production crewmembers in a New Century production were summoned by police officers next to the building’s door. The officers, posted in the nearby square, were verifying the production team’s paperwork. Had it not been valid, the shooting day would have been endangered. While this paperwork entitled the crew to police protection in principle, the verification was prohibitory in intent. Once the paperwork was cleared, the policemen went back to their street duties.

This on-set situation and the complex process of issuing permits seem to be distinctive of Egyptian media production. Omar el-Zohairy, an experienced assistant director, talked about his one-time experience on an advertising set in South Africa.[3] He set a complete contrast with his experience in Egypt: he lauded the ease with which he was able to secure shooting permits (by phone!); the competence with which South African police officers blockaded the streets on demand; the far and few interruptions occasioned by passersby. This, he said, would be impossible to ensure in Egypt. Although Zohairy’s narrative may be overstated, it is easy to see why the Egyptian case stands out against countries that encourage foreign investment in on-location shooting—e.g., in the Arab world, Morocco.[4] The work of getting a permit and the protection offered by permit-granting institutions is very different in the Egyptian case. Even in industries where on-set protection is minimal, as in Hong Kong, there seems to be little in the way of a permit-issuing burden[5]. In Egypt, by contrast, police protection is rarely available on set, even with a permit in hand. These permits are still necessary to ward off costly interruptions on set. Thus, the permit is not a document guaranteeing a certain set of rights: it is an amulet against unwanted delays by the police or, as the case may be, bothersome citizens.

It is unnecessary to carry every single permit on set under all circumstances. When shooting in a precinct where production crewmembers have good relations with the police, it may suffice to carry the permits issued by the Ministry of Interior and the Prefecture, without the local department’s permit. However, trying to shoot on a street where policemen have not been alerted would risk bringing the set to a halt, to the point where entire shooting days may be cancelled. This is without mentioning cases in which, even with all state-sanctioned permits, policemen try to interrupt the set in order to obtain extra payment. A similar tactic is used by so-called “thugs” (baltagiyya) in “difficult” shooting areas like al-Ḥattaba. In such circumstances, significant sums of money are solicited in exchange for protection in the neighborhood (or, more likely, protection against being interrupted). These payments are not always extorted: some productions willingly pay policemen or local “thugs” when they need extra manpower to blockade a street, or to engage in some such task of crowd control.

Permits are not seen as legally binding documents, then, but they are important elements in on-the-street negotiations over the right to shoot. Their legality, in other words, is not necessarily what explains their efficacy. Permits are efficacious to the extent that they can look “official” enough to exempt the set from interruption, and evaluations of “officialdom” vary according to individuals and their positions. Local citizens unhappy to see a camera could be satisfied by the mere look of a government seal, contrary to the policeman who is looking for a more specific set of seals. For example, on a film set in 2014, a director friend suddenly contacted a production crewmember in a hurry.[6] S/he urged him to bring as many official documents as possible with the movie’s name on it. Since we were shooting without a permit, the director’s urge to get this legally irrelevant paperwork was intriguing. When the production worker came by, the director explained that these papers will be sufficient to show any local that the shooting was state-sanctioned and, therefore, that they should not mess with it. With great confidence, s/he added that the police would never stop by to verify their papers. In hindsight, this was an accurate observation about policing habits in this “difficult” area.

Another concrete example, relayed by an experienced assistant director,[7] reinforces the same point. A short while after President al-Sisi had issued a ban on ambulant salesmen in downtown Cairo, this assistant director was shooting a scene with an extra playing the role of an ambulant salesman. While the cameraman took a shot, a vehicle quickly stopped by the extra, captured him, and drove off. In awe, the assistant director pursued the vehicle with some crewmembers. A long conversation ensued with the policemen driving the vehicle: they were told that the captured extra was an actor, not a salesman; that the shooting was perfectly legal; that the crew had a permit issued by the local police department; and that the cameras should have alerted the overzealous policemen to this fact. The police, whom the assistant director would later discover were affiliated to the province of Cairo security (shurtit al-marāfi’), said that they should have notified their specific office twelve hours in advance. In the end, he did not allow the shooting back on the streets. Since the permits issued by the Ministry of Interior held insufficient authority in the Cairo security’s eyes, the shooting day was ruined.

What should attract our attention, here, is the lack of coordination between two state institutions that, in principle, ought to have been coordinated. A permit issued by the Ministry of Interior is not valid according to the province of Cairo official, even though the set was (for once) accompanied by a police officer from the downtown department in Kasr al-Aini. Moreover, the permit’s legality was not sufficient to allow the shooting to continue. In a political context where ambulant salesmen were targeted by presidential decree, it was necessary to convince an official from an institution that does not usually issue permits to let a legal shooting go on, to no avail.

Street Politics

On-location shooting invariably involves negotiations between the production team, local law enforcement, and ordinary citizens. These negotiations, in turn, invariably constrain the narrative desired by the creative crew. Even when state actors are not engaged in suppressing the filmmaker’s ability to express his/her opinions, negotiations with local residents can occasion the same effect. This is what young director Ahmad Abdalla saw as the most prevalent form of censorship in today’s film industry: it is not so much the official censorship board that hinders his artistic progress, but more so the citizens who interfere with his set.[8] In my own experience and through interviews with numerous Egyptian filmmakers, there are three major reasons why citizens interfere with a set, setting aside the playful interruptions of boisterous (usually male) passersby.

First, some citizens interpret the presence of a camera snooping around their neighborhood as a violation of privacy. On the set of Ahmad Fawzi Saleh’s Poisonous Roses (in postproduction), it was not infrequent to find a man screaming that “there are women and children around” when we started shooting. Since women and children are core representations of the “private sphere” in a popular Egyptian context, these cries can be interpreted as an expression of outrage at the presence of a camera—the ultimate unveiling apparatus—in a space that ought to remain under the patriarch’s cover. This interpretation bears a wider meaning than the individualized conception of privacy prevalent in Western liberal societies. From a male perspective, indeed, a street that would be considered part of the public domain in a Western setting becomes “private” as soon as women and children can roam around.

That said, this is not the only interpretation of the men’s interruptions: Fawzi Saleh would say that they were engaged in social theatre in order to obtain more money from the production team. This brings the second reason why citizens may feel emboldened to interrupt a shooting, especially in areas with no police presence. The accountant in Poisonous Roses told me about a TV drama where they shot in a desert near Sixth of October City, in an area controlled by Bedouin groups. According to the accountant, the production team had made all necessary paperwork without making contact with the local Bedouins. Slighted, the locals circled the star’s caravan with their motorbikes and demanded to be paid before allowing the shooting to proceed. The production swiftly obliged, at heavy cost. While this particular area may have never been under strong police control, the visibility of the police on Cairene streets has generally diminished since the 2011 revolution. Thereafter, local protection needed to be sought—and in some cases bought—in order to prevent costly delays in various locations (including where Poisonous Roses was shot).

Lastly, citizens interrupt film sets because they dislike the way in which they are represented in Egyptian or Arabic mainstream media. When a citizen notices a professional camera carried by any crewmember, it is sufficient evidence to the effect that this shooting is “on television.” Scouting in Poisonous Roses involved several experiences in this sense. On one day near Ain al-Sira lake, an older lady living in one of the many informal houses built on the lakeshore started complaining over and over again to the crew that the government should do something about these houses. Her complaints were expressed in an affective mode very similar to the litanies broadcast on populist TV programs like Riham Said’s show, seeking to “expose” the people’s suffering by creating “scandal.” She repeatedly asked us to contact “someone in charge” when we go back to the television station. We had to assure her several times that we were not a television crew, and that we were not filming on that day. One might presume that she saw television as a direct conduit into “the state,” which might be able to sort out her problems.

On another occasion, we were denied access to the roof of a building where we wanted to take a bird’s eye view on our shooting location. The owner said that he had a bad experience with a TV show, which ended up portraying his neighborhood in a negative light. Therefore, he wanted nothing to do with our scouting crew, even though we did not want to take any image of his neighborhood. Likewise, while scouting at night in a popular residential neighborhood nearby, our group was mistaken for an Al Jazeera crew. At a time where the Qatari channel was under fire because of its continued support for the ousted Muslim Brotherhood, it was understandable that we would be retained by the man who had stopped us. At last, a local relative who knew our crew intervened on our behalf to explain that we had nothing to do with Al Jazeera. In any case, the sight of a camera on the streets was sufficient to spur suspicions over our links to the evil television channel, and cast aspersions on our intent. The fact that we were still scouting certainly allowed these experiences to happen without significant delays on our work, yet it could have been costly had it happened on a shooting day.

The anxieties provoked by the sight of a camera on the streets of Cairo are shared by the citizenry and by the police alike: this is one of the most tangible legacies of the 2011 revolution. The camera’s ability to reveal and/or disfigure local reality to a wider audience—i.e., “on television”—is as feared by the citizen concerned with the reputation of his neighborhood as it is by the police officer concerned with “Egypt’s reputation.” The latter notion is often invoked to criticize movies that shine too negative a light on Egypt as a nation, including by showing poverty, dirtiness, and inequality.[9] Since the 2013 coup, in particular, a camera on the streets has become a visible opportunity to interrogate its bearer on his/her patriotism. This impinges on the set when production crewmembers are not armed with the correct paperwork, or when they cannot secure the approval of local residents.

On “State Control”

Two empirical points serve to unsettle the assumption that “the state,” as a single agent, controls film production in Egypt. First, there are many institutions involved in issuing permits: the Censorship Authority, the Cinematic Syndicate, the Actors’ Syndicate, the Ministry of Interior, and in some cases, the military, the Ministry of Antiquities, the Ministry of Islamic Endowments, and the Ministry of Tourism. Some laws are enforced by all these institutions in concert—e.g., when a police officer stops a set without a Ministry of Interior permit, which is itself issued based on censorship and syndicate approval. However, these institutions are not always in common accord—e.g., when a shoot was stopped because the Ministry of Interior had not alerted Cairo security to the presence of an extra dressed as an ambulant salesman. Thus, the work of coordination across these various institutions cannot be taken for granted, as though “the state” works automatically. Rather, this coordination should be observed as a result of contingent decisions by filmmakers, bureaucrats, and on-the-ground law enforcement. When state control works, in other words, its success should be explained rather than presumed.

Second, there is an important material dimension to the efficacy of film permits in Egypt. Permits are not just efficacious because they are legal, but because they enact in print a certain set of seals that will look “official” enough to convince a police officer or a citizen that the shooting is legal. Even the work of issuing permits requires a set of physical letters whose composition is regimented by a specific ideology of officialdom. This material quality, again, cannot be subsumed under the automatic working of state control. The physical permit is not a superfluous addition to otherwise transparent communication channels between the film project and the state. Nor is it a straightforward instantiation of the right to shoot in a specific location. Rather, the permit carries a certain weight in on-the-ground negotiations between filmmakers, the police, and local residents, with the expectation that it should—but will not necessarily—ward off costly delays.

In sum, one cannot simply assume that “the state” is a single agent controlling media production, since state institutions constitute a fragmented system designed to issue censorship approvals, syndicate letters, and a set of police permits, which are in turn unevenly verified by law enforcement. State-centric accounts of media control ignore the labor involved in getting out permits and in enforcing their legality. What is doing the controlling is not a central agent, then, but a series of social actors operating in more or less coordinated institutions and engaged in interpersonal transactions via paperwork. Following Abrams[10] and Mitchell,[11] this analysis bears a much wider point about the Egyptian state: namely, that the commitment to attributing all concrete instances of control to a central state is an ideological effect fostered, in parallel, by state institutions and a large portion of the citizenry. Needless to say, it would take more than indicating the existence of this effect to dispel it, yet it is an important step in improving our analysis of control over media production as usually attributed to “the state.”

Furthermore, the case of Egyptian film permits is an excellent illustration of the way in which state control is diffused through a simple technology—i.e., paperwork—beyond any single institution’s ability to discipline individuals. There is a sense in which, of course, police officers on the street represent a coercive threat to the film crew, yet the overall “control” over film production works in most cases without direct intervention by state actors. In effect, the very idea of getting permits to avoid unnecessary interruptions on set illustrates the way in which institutions have powerful influence without issuing direct commands to media producers.

Conclusion

Writing about “state control” over media production in Egypt seems natural, but this feeling can obscure our analysis, since it can too easily attribute agency to a central source of repression—“the state”—which, in practice, is diffused across various actors and institutions. This argument is well illustrated by the case of film permits in Egypt. Without being the intentional project of a central agency aiming at suppressing subversive narratives, permits constitute a form of control over media production.

This point is intended, in part, to stir reflection among my interlocutors in the Egyptian film industry. According to some, “the state” is a redoubtable obstacle to the work of film production. Oddly enough, left-leaning directors like Ahmad Fawzi Saleh and Hala Lotfy share this opinion with producers like Gaby Khoury and Mohammed el-Adl, who have been members of the Egyptian Cinema Chamber, the official organ representing the industry’s interests to the Federation of Egyptian Industries in the Ministry of Trade and Industry. While Fawzi Saleh and Lotfy argue that the permit-issuing process is a state-sponsored attempt to censor creative work, Khoury and el-Adl complain that the state puts heavy financial restraints over production without providing, among many things, police protection on the streets. “The state” invoked in both cases represents a set of institutions which, empirically, do not always act in coordination. There is no guarantee that the censorship official judging the dangers of a scenario to Egypt’s reputation concurs with the policeman who interrupts a legal shooting to levy extra bribes.

What is noteworthy is that both directors at the industry’s margins and established producers can concur that the state, as a monolithic entity, represents an obstacle to their work. What I have argued in this essay is that this control is distributed over many actors and institutions, that these actors and institutions are imperfectly coordinated via paperwork, and that the Egyptian filmmaker’s “freedom” is curtailed by more than “the state.” Therefore, this essay cannot provide simple recommendations to advance the status of workers in the industry, since any sensible recommendation would have to overhaul existing power structures in Egypt, including the unlimited veto rights given to state censors, the unfettered fining of film workers by public syndicates, and above all, the unwarranted hold of police institutions over both the permit-issuing process and the public domain. However, I would argue that the first step in battling these obstacles is to recognize how “the state” is divisible, and how change will come by standing up against specific institutions, whether the Censorship Authority, the Cinematic Syndicate, or the Ministry of Interior.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

[Figure 1 - For larger version, download

[Figure 1 - For larger version, download